| Sapodilla

- Manilkara zapota |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

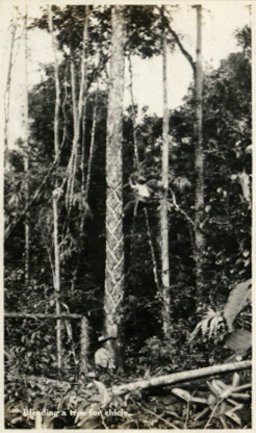

Fig. 1  Sapodilla, Manilkara zapota  Fig. 2  A tree-ripened fruit of the dwarf sapodilla variety ‘Makok’ – tastes like apple pie filling, with notes of caramel, maple syrup, and cinnamon.  Fig. 3  Pinkish new growth  Fig. 4  Leaf habit  Fig. 5  Fruit and flowers emerging  Fig. 6  M. zapota  Fig. 9  Sapota (M. zapota), Madhurawada, Visakhapatnam, India  Fig. 10  Close up of fruit  Fig. 17  Unripe sapodilla oozing latex  Fig. 18  Fruit habit  Fig. 19  Dense canopy  Fig. 20  Tree habit Fig. 21  Plant specimen, Fruit and Spice Park, Homestead, Florida, USA  Fig. 22  Bark  Fig. 23  M. zapota, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami, FL USA  Fig. 24  Incisions on the bark of the chicle tree, M. zapota. Jardín Botánico "Dr. Alfredo Barrera Marín". Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo, México.  Fig. 25 A chiclero bleeding a tree for chicle, Belize  Fig. 26  Protruding hooks on the seed  Fig. 27  Chicle, once used for chewing gum, oozes from the pod of a Sapodilla tree. From Canal Zone, Panama.  Fig. 28  Sari-clad woman in Mysore balancing a basket of chikku (or sapota; a type of fruit) on her head  Fig. 29  The oval shaped Honey Taste sapota fruits (a unique sapota of this region) are sold on a street |

Scientific

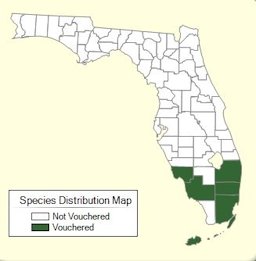

name Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen Pronunciation man-ill-KAR-uh zuh-POE-tuh Common names Baramasi (Bengal and Bihar, India); buah chiku (Malaya); chicle (Mexico); chico (Philippines, Guatemala, Mexico); chicozapote (Guatemala, Mexico, Venezuela); chikoo (India); chiku (Malaya, India); dilly (Bahamas; British West Indies); korob (Costa Rica); mespil (Virgin Islands); mispel, mispu (Netherlands Antilles, Surinam); muy (Guatemala); muyozapot (El Salvador); naseberry (Jamaica; British West Indies); neeseberry (British West Indies); nispero (Puerto Rico, Central America, Venezuela); nispero quitense (Ecuador); sapodilla plum (India); sapota (India); sapotí (Brazil); sapotille (French West Indies); tree potato (India); Ya (Guatemala; Yucatan); zapota (Venezuela); zapote (Cuba); zapote chico (Mexico; Guatemala); zapote morado (Belize); zapotillo (Mexico) 2 Synonyms Manilkara achras, Achras sapota, A. zapota, Sapota achras Relatives Abiu, Pouteria caimito; bully tree, P. multiflora; caimito, Chrysophyllum cainito; caimitillo, P. speciosa; canistel, P. campechiana; cinnamon apple, P. hypoglauca; curiola, P. torta; fruteo, P. pariry; green sapote, P. viridis; macarancluba, P. ramiflora; mamey sapote, P. sapote; lucmo, P. obbovata; lucma, P. macrophylla; nispero montanero, P. macrocarpa; satin leaf, C. oliviforme Family Sapotaceae Origin Central and South America 8 Distribution The United States, Caribbean, Central and South America, Asia, India, Sri Lanka, The Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa 1 USDA hardiness zones 10b-11 Uses Fresh fruit; landscape specimen Height 60-100 ft (18-30m) Spread Pyramidal to rounded canopy; dense; coarse (Fig. 18) Growth rate Slow Longevity Long lived Trunk/bark/branches Branches don’t droop; showy; typically one trunk 6; wood hard and termite resistant; bark is rich in a white, gummy latex called chicle Pruning requirement Trees should be kept at a maximum of about 12-15 feet (3.7-4.6 m) for ease of harvest Leaves Evergreen; 2-5 in (5-13 cm) long; stiff, pointed; clustered at end of shoots; pinkish new growth (Fig. 3) then light to dark green 1 Flowers Small, bisexual, off-white, bell-shaped; borne singly or in clusters in leaf axils near the tips of branches Fruit Berry with brown scruffy skin; round/oval or conical; 2-4 in (5-10 cm); sweet to very sweet; seeds 1-12; fruits mature 4-10 months after flowering 1,8 USDA Nutrient Content pdf Season May-Sept.; peak of the crop June, July; some all year Light requirement Full sun Soil tolerances Tolerant of most soils; grow best in well-drained, light soils; adapted to Florida calcareous soils pH preference 6.0-8.0 Drought tolerance Mature trees are tolerant of drought conditions Flood tolerance Moderately tolerant of flood Aerosol salt tolerance High Wind Tolerance Wind resistant; enduring hurricanes very well 6 Cold tolerance Young trees injured/killed 30 °F ( -1 to 0 °C); mature trees can withstand 28-26 °F (-2° to -3°C) 8 Plant spacing 25 ft (7.5 m) Roots Damage potential high; can form large surface roots (Fig. 23) Invasive potential * Was assessed as invasive in south and central Florida by IFAS Invasive Plants Working Group and is not recommended by IFAS for planting Toxicity The seed kernel (50% of the whole seed) contains 1% saponin and 0.08% of a bitter principle, sapotinin. Ingestion of more than 6 seeds may cause abdominal pain and vomiting.2 Pest resistance Scale insects; no major disease Known hazard The seeds with their hooks represent a chocking hazard (Fig. 26) Reading Material Sapodilla Growing in the Florida Landscape, University of Florida pdf Sapodilla, Fruits of Warm Climates Manilkara zapota: Sapodilla, University of Florida pdf Sapodilla, California Rare Fruit Growers The Sapodilla, Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits Sapodilla: A Potential Crop For Subtropical Climates, Progress in New Crops, Purdue University Origin Sapodilla (Manilkara zapotilla, Sapotaceae) is native to Central and South America, specifically from the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico to Costa Rica, where the largest population of native trees still exists (Gilly 1943). It is now widespread throughout the tropical regions of the world, including Central and South America, the West Indies, India, and Florida in the United States. 8 Distribution Sapodilla is grown on a commercial basis in India, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Mexico, Venezuela, Guatemala, and some other Central American countries. India is the largest producer of sapodilla fruit with current production around 24,000 ha (Chadha 1992). 8 Sapodilla is widely planted in south Florida, where the fruit is marketed locally and shipped to northern and eastern U.S. markets. The fruit, however, is not commonly seen in the United States. In southern Mexico and Central America where sapodilla is native, it is considered to be one of the best of the tropical fruits. 8 Description A superb shade, street (where falling fruit will not be a problem), or fruit tree, Sapodilla reaches a height of 45 feet with a 40-foot spread. The smooth, dark, and glossy, sixi nch- long evergreen leaves are clustered at the tips of twigs and the small, cream-colored solitary flowers appear in the leaf axils throughout the year. The four-inch-wide, scurfy brown fruits have a juicy, sweet, yellow-brown flesh and ripen to softness in spring and summer. The flower-to-fruit period is about ten months. The bark and branches, when injured, bleed a white latex which is the source of chicle, the original base for chewing gum. The trunk on older specimens is flaky and quite attractive, and flares at the base into numerous surface roots. 6 Flowers Notice the imbricated calyx, perhaps in two series, the white corolla, and the single style. Reddish hairs are visible on the calyx and some of the other surfaces in the background. The front view of the chicle flower in the right photo reveals 6 corolla lobes and additional appendages. The whorl of functional stamens attached to the corolla opposite the corolla lobes is also visible. 4

Fruit The sapodilla (M. sapota) is native to Central America, but its unique appeal carried it centuries ago to Southeast Asia, where it has undergone a wonderful transformation. The Maya described it as dainty, fragrant and well tasting - a delicate fruit indeed. Sapodilla is delicious to eat out of hand, and can also be made into a great dessert sauce or mousse. The texture when eaten fresh should be that of a good ripe pear. Elite selections from Asia and the Americas can be eaten skin and all. 3 Fruit maturity occurs anywhere from 4 to 10 months following fruit set, depending on variety, climate, and soil conditions. In south Florida and the Virgin Islands, the fruit appears throughout the year, with a peak season from May to Sept. 8

Fig. 14. A half of a ripe 'Hasya' sapodilla (M. zapota/Sapotaceae) from Fruit and Spice Park, Homestead, Florida Varieties Superior fruit cultivars are available: 'Prolific', 'Brown Sugar', 'Modello', and 'Russel'. Manilkara bahamensis, the Wild Dilly, is native to the Florida Keys and has less desirable fruit. 6 Sapodilla Varieties Harvesting Fruit picked at optimum maturity usually ripen in 4 to 10 days. If you don't know the time of fruit maturity, you may wait until some fruit drop and then begin to harvest those of similar size. Other indicators of maturity are fruit size, loss of peel scurfiness, and a change in skin color from brown to amber. Rub the scurf to see if it loosens readily and then scratch the fruit to make sure the skin is not green beneath the scurf. If the skin is brown and the fruit separates from the stem easily without leaking of the latex, it is fully mature though still hard and must be kept at room temperature for a few days to soften. 2,3 "The longer they are left to soften, the stronger and sweeter the flavour and the flesh colour becomes darker. The flavour is enhanced by putting the fruit in the fridge to cool before eating. The skin can be eaten and in fact is richer in nutritive value than the pulp. I haven't eaten them this way yet, but I think I would like to wash them to remove the scruff layer of the fruit, before eating. The fruits are a good source of calcium, phosphorus and iron." 4 Determining fruit maturity, Tropical Acres Farms Production Seedling trees usually begin bearing in 6 to 7 years or more. Grafted trees may begin to bear in the second to fourth year after planting. After 10 years, a good cultivar may bear 150 to 400 pounds (45-180 kg) of fruit per year. 1 Pollination Isolated sapodilla trees may not be productive because some sapodilla cultivars are self-incompatible. In self-incompatible cultivars, the flowers require cross-pollination by another sapodilla seedling or variety in order to produce fruit. Other varieties may not require cross-pollination but produce more fruit when cross-pollinated. 1 Propagation Seeds should not be used for producing new trees because it takes a long time for trees to begin production and there is also a lot of variability among seedling trees. Marcottage (air layering) has not been an effective propagation method. Side veneer and cleft grafting on to seedling sapodilla rootstock are the most common grafting methods. Chip budding can also be used. Scions or bud sticks are chosen from young terminal shoots. Cover the grafted scions completely with grafting tape. The best time to graft is late summer and early fall. 1 Top working undesirable mature sapodilla trees may be accomplished by cutting trees back to a 3-ft-height stump, white washing the entire stump and then veneer-grafting several new shoots when they reach ½ inch (13 mm) in diameter or larger. 1 Sapodilla Clonal Propagation, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia A successful Method for Propagating Sapodilla Trees, Florida State Horticultural Society Culture Sapodilla has proven to be tolerant of dry conditions, and its ability to thrive on poor soils makes it an ideal fruit tree for less-than-optimum growing areas. The tree has shown ability to withstand extended periods of waterlogging, and trees are grown on most soil types, from clay soils to almost pure limestone. Sapodilla is remarkably tolerant of high levels of root zone salinity (Mickelbart and Marler 1996), a rare characteristic in tropical fruit species. It has also proven tolerant of salt spray off the coast of Florida, indicating it may thrive on the subtropical coasts of other regions as well. 8 Pruning The development of a strong limb framework is important to allow sapodilla trees to carry large crops of fruit without limb breakage. If the tree is leggy and lacks lower branches, remove part of the top to induce lateral bud break on the lower trunk. In addition, shoot tip removal (1 to 2 inches) of new shoots of about 3 feet in length, once or twice between spring and summer will force more branching and make the tree more compact. Remove any limbs that have a narrow crotch angle because these may break under heavy fruit loads. 1 As trees mature, most of the pruning is done to control tree height and width and to remove damaged or dead wood. Trees should be kept at a maximum of about 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m). If the canopy becomes too dense, removing some inner branches will help in air circulation and light penetration. 1 Fertilizing After planting, when new growth begins, apply 1/4 lb (113 g) of a young tree fertilizer such as a 6-6-6-2 (%nitrogen-% phosphate-% potash-% magnesium) with minor elements with 20 to 30% of the nitrogen from organic sources. Repeat this every 6 to 8 weeks for the first year, then gradually increase the amount of fertilizer to 0.5, 0.75, 1.0 lb (227 g, 341 g, 454 g) as the tree grows. Use 4 to 6 minor element (nutritional) foliar sprays per year from April to September. For mature trees, 2.5 to 5.0 lbs of fertilizer per application 2 to 3 times per year is recommended. 1 Irrigation Young sapodilla trees have been observed to defoliate or decline due to lack of water; therefore young trees should be watered periodically during dry periods. Mature sapodilla trees are tolerant of dry soil conditions. However, for optimum fruit production and quality, periodic irrigation during long dry periods is recommended from flowering through harvest. 1 Pests Sapodilla has relatively few insect pests. Occasionally, several moth species (e.g., Barnisia myrsusalis) causes extensive damage to blooms in some years in Florida. The fruit of some cultivars is susceptible to the Caribbean fruit fly (Anastrepha suspensa). 1 Food Uses The ripe sapodilla, unchilled or preferably chilled, is merely cut in half and the flesh is eaten with a spoon. It is an ideal dessert fruit as the skin, which is not eaten, remains firm enough to serve as a "shell". 2 Sapodilla fruit are soft, sweet and have a beautiful smell when ripe. The fruit has a flavor that is a combination of peaches, pears, brown sugar, cinnamon and a little brandy. 7 Sapodilla Recipes, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Virtual Herbarium Database Sapodilla - a Delicious Dehydrated Product, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Sapodilla (Chiku) as a delicate dessert, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Medicinal Properties ** Because of the tannin content, young fruits are boiled and the decoction taken to stop diarrhea. An infusion of the young fruits and the flowers is drunk to relieve pulmonary complaints. A decoction of old, yellowed leaves is drunk as a remedy for coughs, colds and diarrhea. A "tea" of the bark is regarded as a febrifuge and is said to halt diarrhea and dysentery. The crushed seeds have a diuretic action and are claimed to expel bladder and kidney stones. A fluid extract of the crushed seeds is employed in Yucatan as a sedative and soporific. A combined decoction of sapodilla and chayote leaves is sweetened and taken daily to lower blood pressure. A paste of the seeds is applied on stings and bites from venomous animals. The latex is used in the tropics as a crude filling for tooth cavities. 2 Other Uses Chicle: A major by-product of the sapodilla tree is the gummy latex called "chicle" (Fig. 27), containing 15% rubber and 38% resin. For many years it has been employed as the chief ingredient in chewing gum but it is now in some degree diluted or replaced by latex from other species and by synthetic gums. 2 Timber: The valuable wood is homogenous, deep red in colour, very hard, strong, tough, dense, resistant and durable. It is suitable for heavy construction, furniture, joinery and tool handles. 10 Note (Fig. 26) Care must be taken not to swallow a seed, as the protruding hooks might lodge in the throat. 2 General The name sapodilla is derived from the Spanish word zapotilla, meaning "small sapote." 8 Chicle is a natural gum traditionally used in making chewing gum and other products. It is collected from several species of Mesoamerican trees in the genus Manilkara, including M. zapota, M. chicle, M. staminodella, and M. bidentata. 9 The tapping of the gum is similar to the tapping of latex from the rubber tree: zig-zag gashes are made in the tree trunk and the dripping gum is collected in small bags. It is then boiled until it reaches the correct thickness. Locals who collect chicle are called chicleros. 9  Fig. 26 Species distribution map Further Reading Sapodilla, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Virtual Herbarium Database Tropical Fruit Urban Forestry At The Whitman Tropical Fruit Plaza Of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Florida State Horticultural Society pdf Cost Estimates of Producing Sapodilla in South Florida, University of Florida pdf Sapodilla, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Sapodilla in Australia, Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia Manilkara zapota, Agroforestree Database Sapodilla, Tropical Fruit Growers of South Florida Sapodilla, Tropical Fruit News, RFCI Sapodilla Botanical Art List of Growers and Vendors |

||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 Crane, Jonathan H., et al. "Sapodilla Growing in the Florida Home Landscape." Horticultural Sciences Department, UF/IFAS Extension, HS-1, Original Pub. May 1973, Revised Apr. 1994, Nov. 2016, Nov. 2000, Oct. 2005, and Oct. 2008, Reviewed Dec. 2019, EDIS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 4 July 2017, 13 Apr. 2020. 2 Fruits of Warm Climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, 1987. 3 Ledesma, Noris. "Sapodilla (Chiku) as a delicate dessert." Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami Herald, 5 May 2013, fairchildgarden.org. Accessed 28 Apr. 2015. 4 Oram, A. "Sapodilla." Archives of the Rare Fruit Council of Australia, Sept. 1996, rfcarchives.org.au. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. 5 Carr, Gerald D. "Sapotaceae, Manilkara zapota, chicle." University of Hawai'i, Botany Department, Mānoa Campus Plants, botany.hawaii.edu. Accessed 1 May 2015. 6 Gilman, Edward F., et al. "Manilkara zapota: Sapodilla." Environmental Horticulture, UF/IFAS Extension, ENH-564, Original Pub. Nov. 1993, Revised Dec. 2018, EDIS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Accessed 4 July 2017, 13 Apr. 2020. 7 Ledesma, Noris. "Sapodilla." Fairchild Tropical Garden Virtual Herbarium, virtualherbarium.org. Accessed 28 Apr. 2015. 8 Mickelbart, M. V. "Sapodilla: A Potential Crop For Subtropical Climates." Progress in New Crops, Edited by J. Janick, pp. 439-446, 1996, NewCROP™, hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1996/V3-439.html. Accessed 7 Nov. 2020. 9 "Chicle." Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicle. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. 10 Orwa, C., et al. "Manilkara zapota (L.) van Royen." Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide, version 4.0, 2009. www.worldagroforestry.org/af/treedb/. Accessed 4 July 2017. Photographs Fig. 1,3,26 Robitaille, Liette. "Sapodilla 'Alano' Series." 2015, www.growables.org. Fig. 2 Hepworth, Craig. "A tree-ripened fruit of the dwarf sapodilla variety ‘Makok’ – tastes like apple pie filling, with notes of caramel, maple syrup, & cinnamon." Florida Fruit Geek, 31 May 2020, floridafruitgeek.com/2020/05/31/dwarf-sapodilla-varieties/. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020. Fig. 4,19,22 Reimer, J., and Stubler, C. "Manilkara zapota Tree Record." SelecTree, 1995-2015, selectree.calpoly.edu. Accessed 28 Apr. 2015. Fig. 5,6 Vinayaraj. "Manilkara zapota." Wikimedia Commons, 2014, commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. Fig. 7,8 Carr, Gerald, D. "Manilkara zapota Sapotaceae." University of Hawai'i, Botany Department, Mānoa Campus Plants, botany.hawaii.edu. Accessed 1 May 2015. Fig. 9 Adityamadhav83. "Sapota (manilkara zapota). Madhurawada in Visakhapatnam." Wikimedia Commons, 2012, commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. Fig. 10 Tu7uh. "Manilkara zapota." Wikimedia Commons, 2013, commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. Fig. 11,12,13,15,16 Ghosh, Asit K. "Manilkara zapota (L.)." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2020, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu. Accessed 27 Apr. 2016. Fig. 14 Ghosh, Asit K. "A half of a ripe Hasya sapodilla (Manilkara zapota / Sapotaceae) from Fruit and Spice Park, Homestead, Florida." Wikimedia Commons, 25 June 2005, (CC BY-SA 3.0), GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Sapodilla#/media/File:Sapodilla_Hasya03_F&SPark_Asit.jpg. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. Fig. 17 User R1CH~commonswiki. "Unripe Sapodilla (Manilkara zapota) fruit." Wikimedia Commons, 19 May 2006, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Manilkara_zapota#/media/File:Sapodilla_fruit.jpg. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. Fig. 18 "Manilkara zapota, Manilkara achras, Achras sapota." Top Tropicals, toptropicals.com. Accessed 1 May 2015. Fig. 21 Daderot. "Plant specimen in the Fruit and Spice Park - Homestead, Florida, USA." Wikimedia Commons, 16 Mar. 2017, (CC0 1.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Manilkara_zapota#/media/File:Manikara_zapota_0zz.jpg. Accessed 7 Nov. 2020. Fig. 23 Stang, David J. "Manilkara zapota (L.) P.Royen. Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami, FL USA." Wikimedia Commons, 16 Feb. 2007, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manilkara_zapota_22zz.jpg. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020. Fig. 24 García, Luis Fernández. "Manilkara zapota, corteza con incisiones. Árbol del chicle. Jardín Botánico «Dr. Alfredo Barrera Marín». Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo, México." Wikimedia Commons, 4 July 2007, (CC BY-SA 2.5 ES), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manilkara-zapota-yucatan.jpg. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. Fig. 25 "A chiclero bleeding a tree for chicle, Belize." Colonial Office Photographic Collection, The National Archives (UK), Catalogue Ref.: CO 1069/254, 1 Jan. 1917, Wikimedia Commons, via Flickr, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Belize-chicle.jpg. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020. Fig. 27 Culbert, Dick. "Chicle, once used for chewing gum, oozes from the pod of a Sapodilla tree. From Canal Zone, Panama." Wikimedia Commons, 2008, (CC BY 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org. Accessed 28 Apr. 2016. Fig. 28 Wen-Yan King. "Sari-clad woman in Mysore balancing a basket of chikku (or sapota; a type of fruit) on her head." Flickr, 2007, flickr.com. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. Fig. 29 Gpics. "The oval shaped honey taste Sapota fruits (a unique Sapota of this region) are sold on a Street." Flickr, 2007, flickr.com. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. Fig. 30 Wunderlin, R. P., et al. "Species Distribution Map: Manilkara zapota L." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2020, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=214. Accessed 29 Apr. 2015. * UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas ** Information provided is not intended to be used as a guide for treatment of medical conditions. Published 28 Apr. 2015 LR. Last update 8 Nov. 2020 LR |

|||||||||||||||||