In addition to the usefulness of its

fruit, the tamarind has the advantage of being one of the best

ornamental trees of the tropics. it It is particularly valued in

semi-arid regions, where it grows luxuriantly if supplied with

water at the root. From India to Brazil, its huge dome-shaped head of

graceful foliage enlightens many a dreary scene.

The fruit

became known in Europe in the Middle Ages. Marco Polo mentioned it

in 1298, but it was not until Garcia d'Orta correctly described it

in 1563 that its true source was known; it was thought

at first to be produced by an Indian palm. The New England sea-captains

who traded with the West Indies in the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries frequently brought the preserved fruit to Boston from Jamaica

and other islands, but in recent years it has become scarcely known in

the United States. In Arabia and India, however, it is a product of

considerable importance.

When grown on deep rich soils the tree

may attain to 80 feet in height, with a trunk 25 feet in circumference.

The small pale green leaves are abruptly pinnate, with ten to twenty

pairs of opposite, oblong, obtuse leaflets, and soft about ½ inch long.

The pale yellow flowers, which are borne in small lax

racemes, are about 1 inch broad. The petals are five, but the lower two

are reduced to bristles. The fruit is a pod, cinnamon-brown in

color, 3 to 8 inches long, flattened, and ½ to 1 inch breadth. Within

its brittle covering are several obovate compressed seeds sur

rounded by brown pulp of acid taste.

The tamarind is

believed to be indigenous to tropical Africa and (according to some

authors) southern Asia. It has long been cultivated in India and it was

introduced early into tropical America. It succeeds in southern

Florida and has been grown in that state as far north Manatee, where a

large tree was killed in the freeze of 1884.

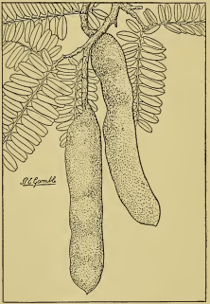

Fig. 56. The tamarind (

Tamarindus indica),

a leguminous fruit-tree

whose brown pods

contain an acid pulp used in cooking, and

to prepare

refreshing drinks.

It not sufficiently hardy to be grown in any part of California.

Yule and Burnell say: "The origin of the name is curious. It is Arabic,

tamar-u'l-Hind, 'date of India,' or perhaps rather in, Persian form,

tamar-i-Hindi. It is possible that the original name may have been

thamar, 'fruit' of India, rather than tamar, 'date.'" In French it is tamarin, in Spanish and Portuguese tamarindo.

The

fruit is widely utilized in the Orient as an ingredient of chutnies and

curries and for pickling fish. In medicine, it is valued by the Hindus

as a refrigerant, digestive, carminative, laxative, and antiscorbutic.

Owing to its possession of the last-named quality, it is sometimes used

by seamen in place of lime-juice. With the addition of sugar and water

it yields a cooling drink or refresco, well known in Latin

America. In some countries tamarinds are an important article of

export. In Jamaica the fruit is prepared for shipment by stripping it

of its outer shell, and then packing it in casks, with alternate layers

of coarse sugar. When the cask is nearly full, boiling sirup is poured

over all, after which the cask is headed up. In the Orient the pulp

containing the seed is pressed into large cakes, which are packed for

shipment in sacks made from palm leaves. This product is a familiar

sight in the bazaars, where it is it retailed in large

quantities; is greatly esteemed as an article of diet by the East

Indians and the Arabs. Large quantities are shipped from India to

Arabia.

The

pulp contains sugar together with acetic, tartaric,

and citric acids, the acids being combined, for the most part, with

potash. In East Indian tamarinds citric acid is said to be present in

about 4 per cent and tartaric about 9 per cent. The following analysis

has been made in Hawaii by Alice R. Thompson: Total solids 69.51 per

cent, ash 1.82, acids 11.32, protein 3.43, total sugars 21.32, fat

0.85, and fiber 5.61. Commenting on this analysis, Miss Thompson says

"The tamarind is of interest because of its high acid and sugar

content.

It is supposed to contain more 435 acid and sugar than any other fruit.

The analysis reported by Pratt and Del Rosario shows the green tamarind

to contain little sugar, but the sugar increases very greatly on

ripening."

The tree delights in a deep alluvial soil and

abundant rain fall. Lacking the latter, it will make good growth

if liberally irrigated. The largest specimens are found in

tropical regions where the soil is rich and deep. On the

shallow soils of south-eastern Florida the species does not attain to

great size. When small it is very susceptible to frost, but when

mature it will probably withstand temperatures of 28° or 30° above zero

without serious injury. It is usually given little cultural attention

and is not grown as an orchard tree.

Propagation is commonly by

means of seeds. These can be transported without difficulty, since they

retain their viability for many months if kept dry. They are best

sprouted by planting them ½ inch deep in light sandy loam. The young

plants are delicate and must be handled carefully to prevent

damping-off. P. J. Wester has found that the species can be

shield-budded in much the same manner as the avocado and mango. He

says: "Use petioled, well-matured, brownish or grayish budwood; cut the

buds one inch long; age of stock at point of insertionof bud

unimportant."

Seedling trees are slow to come into bearing. A mature tree is said to produce, in India, about 350 pounds of fruit a year.

Little is known of the insect pests which attack the tamarind. H. Maxwell-Lefroy mentions two,

Caryoborus gonagra F., Charaxes

fahius Fabr.,

the latter a large black, yellow-spotted butterfly whose larva feeds on

the leaves. Both these insects occur in India.

Thomas

Firminger speaks of three varieties of tamarind which grown in India,

but does not know whether they can be depended on to come true from

seed. M. T. Masters, in the "Treasury of Botany," states that the

East Indian variety has long pods, with six to twelve seeds, while the

West Indian variety has shorter pods, containing one to four seeds.

Seedlings undoubtedly show considerable variation in the size and

quality of their fruit, which accounts for the different "varieties"

which have been noted by many writers. Since none of these has yet been

propagated vegetatively, they are of little horticultural importance.