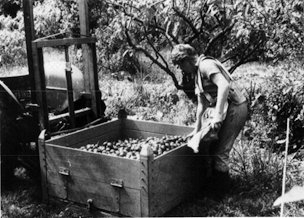

Bay of

Plenty, New Zealand. Tamarillo harvest.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

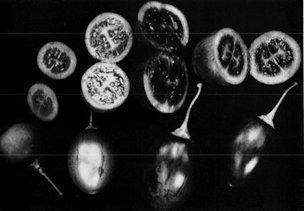

Fruits

occur in clusters. They can be formed year-round, but in seasonal

countries (such as New Zealand) there is a distinct harvesting season.

Because the fruits do not mature simultaneously (unless the tree has

been pruned), several pickings are usually necessary. The fruits pull

off readily, carrying a short stem still attached.

The trees bear

prolifically and yield generous harvests. A single tree may produce 20

kg of fruit or more each year; commercial yields from mature orchards

in New Zealand can reach 15–17 tons per hectare.

In handling

tamarillos, the most serious problem is fungal rot (glomorella) on the

stem, which can quickly extend into the fruit. Copper sulfate (bordeaux

mixture) controls this adequately. The New Zealand Department of

Scientific and Industrial Research has developed a cold-water dipping

process that is also effective. Storage of 6–10 weeks is then possible.

LIMITATIONS

To

develop tamarillo into a practical, widespread crop will not be quick

or easy. Even selected New Zealand cultivars usually produce a variable

product, insufficiently reliable to assure importers that shape, color,

or sugar:acid ratio will remain consistent lot by lot and year by year.

Nor are future yield levels predictable.

Large leaves and brittle

wood make the trees prone to wind damage. Even light winds easily break

off fruit-laden branches. In most locations, permanent windbreaks

should be established at least two years before the plants are set out.

Even then, staking may be needed to keep branches from breaking under

the weight of fruit.

Small,

hard, irregular, “stones,” containing large amounts of sodium and

calcium, occasionally appear in the fruits. They usually occur in the

outmost layers of the fruit and do not present much of a problem in

fresh fruits because those layers are not eaten. In canning, however,

they are a concern because the whole fruit is used. Probably the best

solution is a breeding program to select for types without these

concretions.

The tree is generally regarded as fairly pest resistant. However, some

pests of concern are given below.

Viruses

In most places, viruses are the most significant diseases. They reduce

the plant's vigor and can leave unattractive splotches on the fruit.

Newly emerged seedlings are, as a rule, virus free, but unless

precautions are taken they soon become infected. (The vectors are

mainly aphids.)

4

Nematodes

Root-knot nematodes damage plants, particularly in sandy soils. Insects

The trees are attacked by aphids and fruit flies, and whitefly is

sometimes a serious pest.

5 In the Andes, the

tree-tomato

worm (which also infests the tomato and the eggplant) feeds on the

fruits, sometimes causing heavy losses.

Fungi

The principal fungal disease is powdery mildew, which can cause serious

defoliation.

Dieback

A dieback of unknown origin is at times lethal to the flowers, fruits,

twigs, and new shoots.

RESEARCH NEEDS

Germplasm

Collection

More types need to be collected and information on their economic

traits developed. Identifying and selecting superior

germplasm—especially that found in the Andes—could assist breeding

programs and speed the tamarillo industry toward success.

Breeding

To support the orderly genetic development of this crop, more

information is needed on the plant's reproduction habits and genetics.

Long-term breeding aims should include virus-resistant trees,

low-growing trees, and deeper-rooted trees. To increase yields,

improved fruit set is needed. This is probably not genetic, but the

reason for flower and fruit abortion is not established.

Other breeding goals should be:

• The development of pure seed lines to enable the growing of desirable

ypes from seed;

• Raising sugar:acid ratios;

• Developing fast-maturing and cold-hardy types to increase the area of

potential use in temperate climates; and

• Creating dwarf cultivars.

Plantation

Management Improvements are needed in orchard practice and

management. Among specific research needs are the following:

• Controlling viruses;

• Increasing fruit set;

• Developing fertilizer requirements;

• Learning the ideal pH level;

• Applying trickle and overhead irrigation;

• Developing growing systems;

• Understanding the plant's nutrition; and

• Breaking seed dormancy.

6

Biological control of the tree-tomato worm should be sought for use in

the Andes. (Perhaps

Bacillus

thuringensis would be useful.)

Sweetness

There seems to be a good possibility that the sweetness of the deep-red

fruits can be raised. Already, sweet types are known; however, these

are mostly smaller or less eye-catching. Nevertheless, low-acid red

specimens have been reported.

7 These deserve

greater

attention because the combination of the spectacular red color with a

sweet taste would cause this appealing fruit to take off.

Stones

The cause of the “stones” should be determined, and methods developed

to eliminate or circumvent this nuisance.

Postharvest

Handling

Work should continue on storage and handling to increase shelf life and

to enable tamarillos to be shipped by sea—a development expected to

greatly improve the export situation for most countries. Important

advances have already been made.

Hybrids

Several closely related species (see below) produce good fruit, and

there is the potential of developing hybrid tamarillos, perhaps with

seedless fruits and different flavors. There seem to be substantial

genetic barriers to interspecific hybrids, however.

8

Nonetheless, cell fusion and gene splicing, which seem particularly

easy in Solanaceae, might prove practical.

Tissue Culture

Tissue-culture techniques have been developed for the tamarillo.

Although their main use will be in multiplying improved material for

planting, they are possibly useful in genetic selection and in

propagating of difficult hybrid crosses and haploids. Colchicine

treatment to produce fertile plants from haploids should be attempted.

Work

is currently under way to select a virus-resistant strain with the aid

of tissue culture. In the meantime, however, virus resistance should be

sought in wild species.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name

Cyphomandra betacea (Cavanilles) Sendtner

Family

Solanaceae (nightshade family)

Common Names

Spanish:

tomate de árbol, tomate extranjero, lima tomate, tomate de palo, tomate

francés

Portuguese:

tomate de érvore, tomate francês

English:

tree tomato, tamarillo

Dutch:

struiktomaat, térong blanda

German:

Baumtomate

Italian:

pomodoro arboreo

Origin.

The tamarillo is unknown in the wild state, and the area of its origin

is at present unknown. It is perhaps native to southern Bolivia (for

example, the Department of Tarija) and northwestern Argentina (the

provinces of Jujuy and Tucumán).

Description.

The plant is a fast-growing herbaceous shrub that reaches a height of

1–5 m (rarely 7.5 m). It generally forms a single upright trunk with

spreading lateral branches. The leaves are large, shiny, hairy,

prominently veined, and pungent smelling.

Flowers and fruits hang

from the lateral branches. The pinkish flowers are normally

self-pollinating, but can require an insect pollinator; unpollinated

flowers drop prematurely.

The fruits are egg shaped, pointed at both

ends, 4–10 cm long and 3–5 cm wide, smooth, thin-skinned, and

long-stalked. The skin color may be yellow or orange to deep red or

almost purple, sometimes with dark, longitudinal stripes.

The flesh

inside is yellowish, orange, deep red, or purple. It has a firm texture

and numerous flat seeds. The most flavorful and juicy flesh lies toward

the center of the fruit, becoming more bland toward the skin.

Horticultural

Varieties.

Although there is much variety in the fruits and many local preferences

based on color, there are apparently at present few named cultivars.

Growers normally select their own trees for seed selection.

In New

Zealand, where the most extensive selection has taken place, two

strains are cultivated: red and yellow. Oratia Red (or Oratia Round)

was the first recognized cultivar. The red strain has a stronger, more

acid flavor and is more widely grown. Yellow fruits have a milder

flavor and are preferred for canning. A dark-red strain (called

“black”) was selected in New Zealand in about 1920 as a variation from

the yellow and red types. It was propagated and reselected thereafter.

Environmental Requirements

Daylength.

Unknown; probably daylength-insensitive.

Rainfall.

Cannot tolerate prolonged drought, nor waterlogged soils or standing

water.

Altitude. Unrestricted. Grows at 1,100–2,300 m at the equator in the

Andes; near sea level in New Zealand and other countries.

Low

Temperature. This species is injured by frost. Short

periods below `2°C kill all but the largest stems and branches.

High

Temperature.

In tropical lowlands, tamarillos grow poorly and seldom set fruit.

(Fruit set seems to be affected strongly by night temperature.) The

plant seems to do best in climates where daytime temperatures range

between 16 and 22°C during the growing season.

Soil Type.

Fertile, light, well-drained soil seems best.

Related

Species. The genus

Cyphomandra,

native to South and Central America and the West Indies, contains about

40 species. Many that are grown for their fruits remain to be

investigated. Several are said to produce fruits as good as those of

the cultivated tamarillo. These may hold potential as economic crops in

their own right, or as germplasm sources for improving the tamarillo.

Fruit-bearing species deserving special studies include the following:

Cyphomandra

casana (C.

cajanumensis)

Found growing wild on the edge of rain forests in the highlands of

Ecuador, especially in the Loja Province. Like the tamarillo, the

casana grows rapidly to a small tree, 2 m tall. Its large, furry,

deep-green leaves make it an interesting ornamental, but it also

produces heavy crops of mild-flavored fruits in about 18 months. The

fruits are spindle shaped and golden yellow when ripe. They are sweet,

juicy, and said to be rather like a blending of peach and tomato in

flavor.

The casana seems to need cool growing conditions. Unlike the

tamarillo, the casana fruit is a poor shipper. A breeding program for

selection of firmer, larger, and better colored fruit could yield a

fruit of commercial value. It deserves special attention from

horticulturists and scientists as a source of genetic material for such

qualities as nematode resistance, root rot resistance, fragrance,

flavor, color, and yield.

Cyphomandra

fragrans

Compared with the tamarillo, this tree has greater tolerance to powdery

mildew, a smaller and more robust stature, basal fruit abscission (the

fruits break away clean without the stalk as found on tamarillos), and

a greater degree of cold hardiness. Its fruits resemble small

tamarillos, but have a thick and leathery orange skin. Like most

solanaceous fruit, it is somewhat acid.

Cyphomandra

hartwegi This

species has an extensive natural range, but is not yet commercially

cultivated. Apparently, it has not even been tested as a potential

crop. It has a yellow berry about the size of a pigeon's egg.