From the Manual Of

Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Soursop

Annona muritica L.

For

the preparation of sherbets and other refreshing drinks, the soursop is

unrivaled. Those who have visited Habana and there sipped the

delectable champola de guandbana will agree with Cubans that it is one

of the finest beverages in the world. Soursop sherbet is equal to that

prepared from the best of the temperate zone fruits, if not superior to

all other ices.

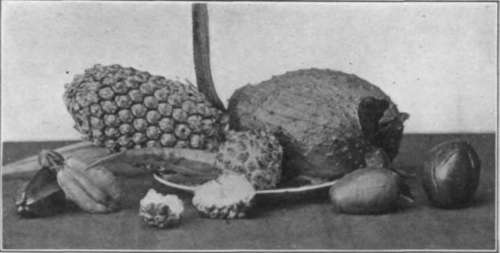

Plate VIII. Upper, the cherimoya at its best; lower, the soursop and

other fruits.

The

tree is more strictly tropical in its requirements than the cherimoya

or the sugar-apple. It withstands very little frost, and succeeds best

in the tropical lowlands. Though widely disseminated, it is nowhere

grown on an extensive scale. This is due, most probably, to the scanty

productiveness which characterizes the species in general. There is an

opportunity here for an excellent piece of work; by obtaining a

productive variety and propagating it by budding, or by increasing the

productiveness of the species through improved cultural methods, the

soursop could be made profitable and of considerable commercial

importance. In the large cities of tropical America there is a good

demand for the fruits at all times of the year, a demand which is not

adequately met at present.

The soursop is a small tree, usually

slender in habit and rarely more than 20 feet high. The leaves are

obovate to elliptic in form, commonly 3 to 6 inches long, acute,

leathery in texture, glossy above and glabrous beneath. The flowers are

large, the three exterior petals ovate-acute, valvate, and fleshy, the

interior ones smaller and thinner, rounded, with the edges overlapping.

The fruit is the largest of the annonas;

specimens 5 pounds in weight are not uncommon and much larger ones have

been reported. It is ovoid, heart-shaped, or oblong-conical in form,

deep green in color, with numerous short fleshy spines on the surface.

The skin has a rank, bitter flavor. The flesh is white, somewhat

cottony in texture, juicy, and highly aromatic. Numerous brown seeds,

much like those of the cherimoya, are embedded in it. The flavor

suggests that of the pineapple and the mango.

Alphonse

DeCandolle says that the soursop "is wild in the West Indies; at least

its existence has been proved in the islands of Cuba, Santo Domingo,

Jamaica, and several of the smaller islands." Safford states that it is

of tropical American origin. The historian Gonzalo Hernandez de Oviedo,

in his "Natural History of the Indies," written in 1526, describes the

soursop at some length, and he mentions having seen it growing

abundantly in the West Indies as well as on the mainland of South

America. At the present day it is perhaps more popular in Cuba than in

any other part of the tropics. In Mexico it occurs in many places, and

the fruit is often seen in the markets. It is also grown in the

tropical portions of South America.

H. F. Macmillan says that it

thrives in Ceylon up to elevations of 2000 feet. It is cultivated in

India, in Cochin-China, and in many parts of Polynesia. Vaughan

MacCaughey states that it is the commonest species of Annona in the

markets of Honolulu. Paul Hubert notes that it is cultivated in Reunion

and on the west coast of Africa.

It will be observed that its

distribution is limited to tropical regions. In the United States it

can only be grown in southern Florida, where with slight protection it

succeeds at Miami and even as far north as Palm Beach. Exceptionally

cold winters, however, may kill the trees to the ground. In California

it is not successful.

The name soursop is of West Indian origin,

and is the one commonly used in English-speaking countries. In Mexico

the fruit is known as zapote agrio, and more commonly as guanabana

(sometimes abbreviated to guanaba), which is the name most extensively

used in Spanish-speaking countries. Guanabana is considered to have

come originally from the island of Santo Domingo. In the French

colonies the common name is corossol or cachiman epineux. Yule and

Burnell say: "Grainger identifies the soursop with the suirsack of the

Dutch. But in this, at least as regards use in the East Indies, there

is some mistake. The latter term, in old Dutch writers on the East,

seems always to apply to the common jackfruit, the 'sourjack,' in fact,

as distinguished from the superior kinds, especially the champada of

the Malay Archipelago." In Mexican publications the soursop is

sometimes confused with the soncoya (A. purpurea),

though it actually differs widely from the latter both in foliage and

fruit.

The

soursop is more tolerant of moisture than the sugar-apple, and can be

grown in moist tropical regions with greater success. Temperatures

below the freezing point are likely to injure it, although mature trees

may withstand 29° or 30° above zero without serious harm.

The

soil best suited to this species is probably a loose, fairly rich, deep

loam. It has done well, however, on shallow sandy soils in south

Florida. F. S. Earle has found in Cuba that liberal applications of

fertilizer will increase greatly the amount of fruit produced. The

formula used is the same as that recommended for the sugar-apple.

Little attention has yet been given to the cultural requirements of the

plant.

The soursop, grown from seed, comes into bearing when

three to five years old. The season of ripening in Mexico and the West

Indies is June to September; in Florida it is about the same.

Mature

trees rarely bear more than a dozen good fruits in a

season. Oftentimes there are produced numerous small, malformed,

abortive

fruits which are of no value. These are due to insufficient

pollination, only a few of the carpels developing normally, the

remainder being unable to do so because they are not pollinated. The

same phenomenon often occurs in the cherimoya, and, less commonly, in

the sugar-apple and bullock's-heart.

Seedling trees differ in

the amount of fruit they yield. Only the most productive should be

selected for propagation. It may be possible still further to increase

their productiveness by attention to pollination, and it has been shown

that proper manuring is a great aid. Since the fruits are commonly of

large size, it cannot be expected that so small a tree will produce

many; still, the average seedling does not bear more than a small

proportion of the crop it could safely carry to maturity, and the

object of future investigations should be to obtain varieties which

will be more productive.

In various parts of the world the tree

is attacked by several scale insects, and the fruits by some of the

fruit-flies, notably the Mediterranean fruit-fly.

Propagation of

the soursop is usually effected in the tropics by seed. Choice

varieties which originate as chance seedlings, however, can only be

perpetuated by some vegetative means.

P. J. Wester has found

that the species can be budded in the same manner as the cherimoya. He

recommends as stock-plants the bullock's-heart and the pond-apple. Seeds are germinated in the same manner as those of

the cherimoya.

Back

to

Soursop Page

|

|