From Neglected Crops: 1492 from a different perspective

by the Food And Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

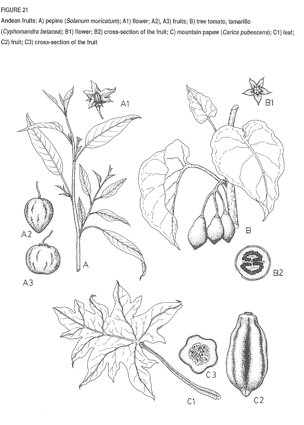

Pepino

(Solanum muricatum)

Botanical name: Solanum muricatum Aiton, S. variegatum R. & P., S. pedunculatum Roem & Schult, S. guatemalense Hort.

Family: Solanaceae

Common

Names:

English: pepino, sweet cucumber, pear melon; Quechua: cahum, xachum;

Aymara: kachuma; Spanish: pepino, pepino dulce (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru,

Bolivia), mataserrano (central and southern Peru), peramelon (Canaries)

The pepino Solanum muricatum,

originates from the Andean region and has been domesticated since

pre-Hispanic times. At present, it is known only as a cultivated

species. Its names in native languages and representations on various

ceramic objects of the Chimú and Paracas cultures are proof that it was

a widespread and important crop in those days. This was not so during

the settlement or the Republic. During the settlement, the Viceroy

Melchor de Navarra, Count of la Patata, prohibited consumption of this

fruit and gave it the pejorative name of "mataserrano" (highlander

killer). The Spanish word pepino might have been intended to facilitate

the introduction of Cucumis sativus

L. (Cucurbitaceae), a species also known by this name, as the names

have been confused since then. On the northern coast of Peru (in the

Virti and Moche valleys), farmers believe that if pepinos are eaten

after drinking liquor, death may result. Names and beliefs have

contributed towards S. muricatum

being grown in small areas and its introduction is still at the

incipient stage. The situation is not the same in the countries where

it has been introduced, however. Commercial crops produced with

advanced technology are known in Chile, New Zealand and the United

States (California) as a result of this fruit's acceptance on North

American, European and Japanese markets.

Uses and applicatons

The fruit of S. muricatum

is eaten ripe as a refreshing, quenching fruit after physical effort.

Herdsmen of Moche and Virti take pepinos in knapsacks for eating during

long treks through the desert. Its yellowish white colour, with

speckles and longitudinal lines, and its purple colour in the ripe

state make the fruit attractive. Its smell and taste are pleasant

because of their typical mild aroma and slightly sweet flavour. Its

nutritional value is low but it is recognized for its diuretic

properties, probably because of its high water content (90 percent) and

good iodine content, for which it is recommended for treating goitre.

It also contains 7 percent of carbohydrates and 29mg per 100 g of

vitamin C.

Botanical description

S. muricatum is a

herbaceous plant of a very branching habit and with a woody base. It

has abundant foliage, with simple or pinnate leaves (one to three pairs

of folioles) and elliptical-lanceolate, strigose or glabrous laminae

and folioles. The inflorescence is subterminal with few flowers. The

flowers are pentamerous, the calyx persists on the fruit and the

actinomorphous corolla is 2 cm in diameter and bluish in colour with

whitish margins.The stamens are shorter than the corolla, the anthers

are yellow, connivent and dehiscent through apical pores. The style

emerges slightly in between the anthers. The fruit is ovoid, conical to

subspherical, and it may be with or without seeds.

Phenology

Plants propagated vegetatively grow quickly and begin to flower four or five months after sowing.

The biological cycle with this kind of propagation is as follows:

• Cuttings taking root: this is very quick (ten to 15 days) in damp soil.

• Vegetative growth: this is manifested by branches and leaves emerging in abundance and lasts three to 3.5 months.

• Flowering and fruiting: this is abundant because of the number of branches and lasts 1.5 to 2.5 months.

• Postharvest stage: this is a period of rest for the plant during

which no branches or leaves are put out; it is the right time for

taking cuttings for propagation and at the same time for pruning the

plant.

• Resprouting: with greater humidity, the plant begins a new phenological cycle.

Plants

propagated by seed take longer to develop. In spite of the fact that

the plant is perennial, growers only avail themselves of two fruiting

seasons, since fruit yield and quality subsequently diminish.The seeds

viability after removal from the fruit is not known but, in the

vegetable gardens where they are grown, seedlings frequently appear. In

the laboratory, seedlings have been obtained even after 15 to 20 days

of seed drying.

Ecology and phytogeography

S. muricatum

is a tropical species of temperate,mountain and coastal climates. In

the Andean region, cultivation takes place in the inter-Andean valleys

and on the western slopes, from 900 to approximately 2,800 m. These

boundaries are set within 24°C at the lower limit and 18°C a tthe upper

limit, with an annual precipitation of between 500 and 800 mm. The

climatic characteristics described correspond to the high part of the

subtropical dry forest and the low dry mountain forest or to the high

yungas and quechua of Peru. Coastal cultivation takes place south of

lat. 7°S. during the autumn and winter when the temperature fluctuates

between 21 and 17°C and atmospheric humidity increases as a result of

mists and drizzle.The original cultivation of S. muricatum

extended along the Andes, from southern Colombia to Bolivia and the

Peruvian coast. During the settlement, it was introduced into Mexico

and Central America, where it was known as S. guatemalense.

Genetic diversity

The

species displays wide intraspecific variability, which has given rise

to the aforementioned synonymy. Morphological variation is evident

in the division of the leaf lamina (compound and simple), the pubescence

of the stems and leaves (glabrous-strigose) and the shape, colour and

consistency of the fruit. A physiological variation has been detected

in the formation of the fruit and seeds, since there are certain

biotypes that produce fruit after pollination and contain fertile seeds

and others which, owing to the sterile pollen, form parthenocarpic

fruit without seeds. Correlations have not been established between the

characteristics described, and they warrant specific research.

Varieties and forms have been described. As regards varieties,

Protogenum is characterized by compound leaves and Typica by simple

leaves. Within the latter, the form glaberrimum, which has glabrous leaves, is distinctive.

Related wild species

This is a still undefined aspect. Research based on interspecific crossings reports S. muricatum with S. caripense H. & B.ex Dun., S. labanoense Correll and S. trachvceirpum

Bin & Sodiro. Of these, the first is regarded as having greater

potential for such genetic affinity in that fertile hybrids have been

obtained.There is less evidence in the case of the other species but,

in that of S. tabanoense, the origin of S. muricatum could be southern Colombia and Ecuador, since this is the natural area of distribution of the species to which it is related.

Known cultivars and centres of diversity

On the sierra of Cajamarca in Peru, the typical form of S. muricatum

is found with regular frequency, with subspherical fruit, a pressed

apex, and in a yellowish green colour with some purple speckles. On the

Peruvian coast, the form glaberrimum has been 'found in pure and commercial crops, of which two cultivars can be distinguished:

Morado listado:

This has dark green leaves, suberect branches and ovoid-conical fruit

of variable size. It has a yellowish, very sweet mesocarp. This is the

fruit most valued on the market.

Oreja de burro:

This has light-green leaves and long branches; it is semi-prostrate,

has elongated conical, large or medium fruit with little

pigmentation (white pepino) and its mesocarp is sandy white and less

sweet.

The variety Protogenum

has been described in the case of Colombia and Ecuador, where cultivars

are unknown. On the northern coast of Peru, a purple pepino is known,

which is subspherical in shape and very sweet. The growers consulted

say it has disappeared.

Living material needs to be collected throughout the distribution area of S. muricatum in order to set up a gene bank.

Cultivation practices

Propagation

is generally by cuttings. To prepare the cuttings, healthy, mature

branches are selected and cut at a length of 30 to 35 cm. They are then

left in the shade for two to three days to induce a slight dehydration

and encourage rapid rooting. The soil, with sufficient humidity, is

prepared by ploughing in furrows. After four to five days, the furrow

is "cleared'', which consists of breaking up the soil and deepening the

furrows to achieve a good infiltration of water, without waterlogging

the ridge. The cuttings are planted 50 cm apart under damp conditions,

on the lower third of the side of the ridge. The distance between

furrows is 80 cm.

Tilllage consists of irrigation, hoeing

and earthing up. Irrigation is frequent during the first few days after

sowing and is then carried out at intervals as required. When the fruit

is ripening, irrigation is suspended. Earthing up is carried out 30 to

35 days after sowing and is used to bury the fertilizer.

In Peru S. mumricatum is not grown very much commercially and the yield per unit of area is not known, nor is the extent of its cultivation.

Prospects for improvement

The limitations in the countries of origin are determined by:

the "social marginalization" of the fruit, which is the reason for its low consumption;

• the underuse of genetic variability;

• a lack of commercial techniques;

• inadequate transportation of the fruit.

However, these limitations are not factors which definitively prevent extensive cultivation of S. muricatum.

This is one of the native species with the greatest potential for

overcoming its current marginalization, as the availability of fruit

can easily be diversified and the potential for consumption and export

widened.

Lines of research

Sustained promotion of S. muricatum cultivation must be based on a multidisciplinary research program that includes:

•

botanical explorations within its primary distribution area that

make it possible to recognize the extent of intraspecific variability

and to define the centres of genetic diversity;

• anatomical

and morphological, floral biology and cytogenetic research to interpret

ecophysiological behaviour and genetic variability;

• research

into phenology and agronomic culivation techniques in various

ecological areas in order to establish nutritional and health

requirements and yield potential.

|

© FAO 1994

|