Pepino

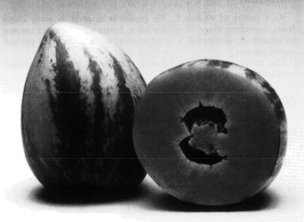

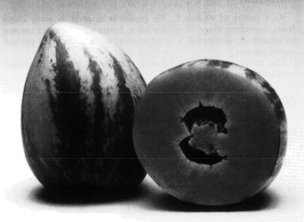

The pepino dulce 1 (Solanum muricatum)

is a common fruit in the markets of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia,

and Chile. It comes in a variety of shapes, sizes, colors, and

qualities. Many are exotically colored in bright yellow set off with

jagged purple streaks. Most are about as big as goose eggs; some are

bigger. Inside, they are somewhat like honeydew melons: watery and

pleasantly flavored, but normally not overly sweet. 2

Despite

the fact that South Americans enjoy this fruit, there seems to be a

curious lack of awareness for its commercial possibilities elsewhere.

Although pepinos are related to, and grown like, tomatoes, they

nevertheless remain a little-known crop, and their various forms are

currently unexplored and underexploited.

This plant's obscurity may

not last much longer. In Chile, New Zealand, and California, the pepino

(pronounced peh-pee-noh) is beginning to be produced under the most

modern and scientifically controlled conditions. As a result,

international markets are opening up. For example, the fruit has

recently been successfully introduced to up-scale markets in Europe,

Japan, and the United States.

In Japan, consumers have an insatiable

appetite for pepinos, and in recent years they have bought them at

prices among the highest paid for any fruit in the world. Pepinos are

offered as desserts, as gifts, and as showpieces. Often they are

individually wrapped, boxed, and tied with ribbons. Some trendy stores

display pepinos whether they sell or not.

Its success in Japan is

perhaps an indication of its future: the pepino is attractive, it has a

good shelf life, it is tasty, and its shape and compact size are ideal

for marketing.

PROSPECTS

The Andes.

Pepino is an ideal home garden plant; it grows readily from cuttings

and is cheap to produce, and increased demand could greatly benefit

home producers. Given attention by horticulturists, a colorful array of

pepino types—both traditional and newly bred—could bring increased

appeal to consumers from Colombia to Argentina.

The transition to

more extensive production has already begun. In the coastal valleys of

Peru, there are some large fields of pepinos (usually rotated with

potatoes, corn, and other crops). Lima is provided with the fruits

year- round, and a small export trade has begun. In Ecuador, too, a few

fields are grown under advanced agricultural conditions. In Chile, more

than 400 hectares of pepinos are planted in the Longotoma Valley, and

increasing quantities are being exported, notably to Europe. Formation

of cooperatives to develop markets, coordinate transport, and control

quality could lead to greater local and export earnings.

There are

parts of the Andes that are unaware of this crop. In Colombia, for

instance, it is hardly known in most of the highland departments,

although in San Agustín (Valle) and Manizales (Caldas), there are large

farms (fincas) that specialize in pepinos.

Other Developing Areas.

In addition to its wide cultivation in South America, the plant has

been introduced to Central America, Morocco, Spain, Israel, and the

highlands of Kenya. Relatively unknown in other nations but worth

trying in all warm-temperate areas, this seems to be a crop with a big

future fast approaching. Commercial pepino production has been

suggested for southern Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, the highlands of

Haiti, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, and Mexico—as well as for the cooler

areas of Africa and Asia (particularly China).

Industrialized Regions.

This crop has potential for production in many parts of Europe, North

Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, North America, Australasia, South

Africa, and Japan, although in some areas it may have to be grown under

glass or plastic to produce the sweet, unblemished fruits demanded by

the top-paying markets.

As noted, pepino is already an established

crop in New Zealand. In the United States, it is grown on a small scale

in Hawaii and California, where several hundred hectares are now under

commercial cultivation. This seems to be the beginning of a promising

new addition to the horticultural resources of much of the temperate

zones.

The pepino has been called "a decadent fruit for the '90s." It is sweet, succulent, and melts in the mouth.

USES

The

pepino is so versatile that it can be a component of any part of a

meal: refreshment, appetizer, entree, or dessert. South Americans and

Japanese eat it almost exclusively as a fresh dessert. It is highly

suited to culinary experimentation. For instance, New Zealanders have

served it with soups, seafood, sauces, prosciutto, meats, fish, fruit

salads, and desserts. The fruits can also be frozen, jellied, dried,

canned, or bottled.

Pepinos are often peeled because the skin of

some varieties has a disagreeable flavor. It pulls off easily, however.

The number of seeds depends on the cultivar, but even when present, the

seeds are soft, tiny, and edible, and because they occur in a cluster

at the center of the fruit they are easily removed.

NUTRITION

As

a source of vitamin C, the pepino is as good as many citrus fruits,

containing about 35 mg per 100 g. It also supplies a fair amount of

vitamin A. Otherwise, it is 92 percent water and only 7 percent

carbohydrates.

The fruits are normally subacid. Levels of 10–12 Brix (sugar concentration) are common. 3

AGRONOMY

All

pepino cultivars are propagated vegetatively. Cuttings establish roots

so easily that mist sprays or growth hormones are usually unnecessary.

Tissue culture is also possible. 4

By and large, pepino

is grown like its relatives, tomato and eggplant. With its natural

upright habit of growth and fruiting, it may be cultivated as a free-

standing bush or as a pruned crop on trellises. (Supports can be used

to keep the weight of the fruit from pulling the plant to the ground.)

The plant grows quickly and can flower and set fruit 4–6 months after

planting. It is a perennial but is usually cultivated as an annual.

Undemanding

in its basic requirements, the plant has wide adaptability to altitude,

latitude, and soils. When young, it is intolerant of weeds, but it

later smothers any low-growing competition. Established bushes show

some tolerance to drought stress, quickly recovering vegetative growth,

although their yield may be depressed. In dry regions, irrigation is

normally used.

The plants are parthenocarpic, which means they need

no pollination to set fruit. However, self-pollination or

cross-pollination greatly encourages fruiting.

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

Pepinos

are harvested when fruits have a pale yellow or cream background color

(at least in the popular cultivars El Camino and Suma). Fruits left on

the plant until overripe often have poor flavor. Harvesting must be

done carefully because the fruits bruise easily and finger markings

show up. With current varieties, the fruits on a single bush mature at

different times, and several pickings are necessary throughout the warm

season. Yields of 40–60 tons per hectare are not uncommon, and even

more may be possible under greenhouse conditions.

Auckland,

New Zealand. Over the last 20 years, New Zealand horticulturists have

taken up the pepino as a commercial crop and have developed it,

probably to a greater extent than in any other country. Their varieties

derive from clonal material, introduced from Chile (following heat

treatment to remove viruses).

Today, pepinos are being grown on many

hectares, much of it under glass, and the fruits are shipped to North

America, Japan, and Europe. In fact, since 1984, pepinos have been one

of New Zealand's most lucrative fruit exports. (New Zealand Herald)

The

fruits are susceptible to chilling injury and are stored at 10–12°C. At

this temperature they may keep in good condition for 4–6 weeks. (Sea

freighting may be possible from many countries.) A fruit taken out of

storage has a shelf life of several weeks at room temperature.

LIMITATIONS

The

pepino is a little-studied crop, with sparse factual data or commercial

field experience behind it. Particular areas of uncertainty include the

following.

Fruit Quality Few

sweet varieties also have good horticultural and marketing qualities;

the skin, although edible, is often tough and bitter; and improperly

ripened fruit have a bad aftertaste.

Lack of Adaptability The

best fruit candidates are insufficiently hardy for cultivation in many

cool areas and are susceptible to nematodes. High temperatures retard

their growth and reduce the quality of their fruits, and drought

readily kills the bushes because of their shallow roots.

Horticulture

Cultural conditions and plant nutrition can greatly affect fruit color,

sweetness, taste, and overall quality in ways that are not yet fully

understood.

Fruit Set Poor

fruit set is often a problem. The causes seem to include

over-fertilizing, which fosters vegetative growth rather than

flowering, and high temperatures, which cause the flowers to abort. 5

Pests and Diseases

The plant's susceptibility to pests and diseases in regions of

intensive agriculture is scarcely known. Although attacks have rarely

been of economic importance, more intensive cultivation of larger areas

may intensify disease and pest problems. Aphids, spider mites, and

whitefly already have been serious problems in California and New

Zealand. Nematodes and root rot have also been concerns. In addition,

the plants have shown susceptibility to viruses.

RESEARCH NEEDS

Fruit Quality Research

is needed to better understand the causes of the insipid flavor of many

pepinos. If the flavor can be sharpened and strengthened, the crop's

future will be more secure. Approaches might include analysis of the

effects on flavor of different varieties, stages of picking,

postharvest handling, fertilization, and perhaps the use of salt. 6

Cultivation

Cropping systems have not been investigated in depth, and most

commercial growers rely on tomato technology. Future agronomic research

should include analysis of different cultivation practices, stress

tolerance, plant nutrition and irrigation, light and temperature

requirements, pollination, and methods for training and supporting the

plants (such as trellising).

Plant Physiology

The physiological problems relating to fruit set need to be better

understood. Also, a convenient method for judging ripeness, other than

using fruit color, would be extremely valuable.

Genetic Development

Because pepino reproduces easily by seed, it can be improved readily

through selection of sexual variants from cross-pollination. The mixed

genetic composition (heterozygosity) allows considerable range in

character selection. Added to this, vegetative propagation is simple,

which means that any mutant type can be perpetuated without difficulty

and clonal lines established. 7

Market Development

The creation of a new crop requires the development of marketing as

well as horticulture. Because pepinos are new to consumers outside the

Andes, markets are unstable. Furthermore, there is a lack of basic

marketing knowledge, consumer acceptability is unknown, and ultimate

market demand is uncertain. Promotion and market development could do

much to assure the steady advancement this crop deserves.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Solanum muricatum Aiton

Family Solanaceae (nightshade family)

Botanical Synonyms Solanum variegatum Ruíz and Pavón; Solanum guatemalense Hort., and others

Common Names

Quechua: cachun, xachun

Aymara: 'kachan, kachuma

Spanish:

pepino, pepino dulce, pepino blanco, pepino morado, pepino redondo,

pepino de fruta, pepino de agua, mataserrano, peramelon (Canary Islands)

English:

pepino, Peruvian pepino, pear melon, melon pear, melon shrub, tree

melon, sweet cucumber, mellowfruit, “kachano” (an Aymara derivative

that has been suggested to avoid confusion with melons or cucumbers)

Origin.

The place and time of the pepino's domestication are unknown, but the

plant is native to the temperate Andean highlands. It is known only in

cultivation or as an escaped plant. It is an ancient crop, and is

frequently represented on pre-Columbian Peruvian pottery.

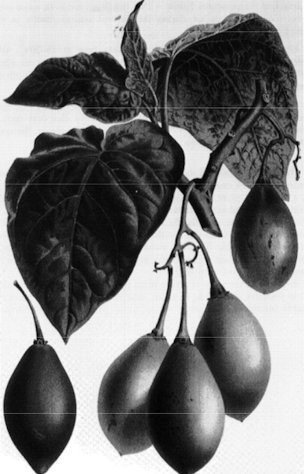

Description.

This highly variable species is a sprawling, perennial herb that

reaches about 1 m in height, with a woody base and fibrous roots.

Several stems may arise from the base, and they may establish roots

where they contact soil. The leaves may be simple or compound; when

compound, the number of leaflets may vary from 3 to 7. The white to

pale-purple to bright-blue flowers occur in clusters. As noted, fruits

can be produced without pollination (such parthenocarpic fruits are

seedless), but fruit set is much greater when self- or

cross-pollination occurs. Pollen is not usually abundant. As the stigma

is longer than the anthers, pollination is unlikely to occur unless

pollen is transferred by an insect or human hand.

The fruit varies

from globose to pointed oval. When ripe, the skin background color may

be creamy to yellow-orange. Purple, gray, or green striping or blush

colorations give the fruit distinctive appearance. The flesh may be

greenish, yellow, salmon, or nearly clear.

Horticultural Varieties.

Pepinos appear in markets throughout the Andes, but although there are

many distinct strains, few have been stabilized into named cultivars.

In

Chile, however, there are named varieties. All produce similar purple-

striped, egg-shaped fruits. These are only slightly sweet, with a Brix

rating generally less than 8. The purple stripes mask the bruise marks

so common on the golden, unstriped pepinos. Chile is a major exporter,

and its varieties are now also grown in California and New Zealand.

In

New Zealand, the most common cultivated varieties are El Camino and

Suma. El Camino has medium to large egg-shaped fruit with regular

purple stripes. For reasons that possibly have to do with mineral

nutrients given to the plant, it sometimes produces off-flavored fruits

(these are identifiable by their brownish green color). Suma is a

vigorous cultivar producing heavy crops of medium to large globose

fruits, with regular purple stripes and attractive appearance. Their

flavor is mild and sweet.

In California, New Yorker is the most

widely grown cultivar. Since 1984, however, Miski Prolific has become

equally popular. Its flesh is deep-salmon color, and its skin creamy

white with light-purple stripes. There are a few seeds in each fruit.

Environmental Requirements.

Although

this plant is native to equatorial latitudes, it is typically grown on

sites that are cool. Thus, it is found in upland valleys, in coastal

areas cooled by fog, and parts of Chile where the summers are not hot.

Daylength. Since the pepino fruits well at many latitudes, it appears to be photoperiod-insensitive.

Rainfall.

1,000 mm minimum, well distributed over several months. As noted, the

pepino has little drought resistance, and in Chile and Peru irrigation

is often used.

Altitude. The plant seems unaffected by altitude. It grows from sea level in Chile, New Zealand, and California to 3,300 m in Colombia.

Low Temperature.

Once established, the plant experiences frost damage at temperatures

below 3°C. Seedlings are even more sensitive. Cool, wet weather during

the harvest season results in skin cracking.

High Temperature.

The plant performs best at 18–20°C. With adequate moisture, it can

tolerate intermittent temperatures above 30°C. However, fruit

production then declines, particularly if both day and night

temperatures are high.

Soil Type.

The plant thrives in moderately moist soils with good drainage. Soils

should be above pH 6.0 to avoid disorders such as manganese toxicity

and iron deficiency. If soil is too fertile, there can be problems of

fruit set and fruit quality.

Related Species. Solanum caripense

(tzimbalo) is a possible wild ancestor, which crosses readily with

pepino and bears edible fruit. It is a sprawling plant, more open and

smaller than the pepino, that is fairly widespread in the Andes between

800 and 3,800 m elevation. Its fruits are elongate and slightly smaller

than ping-pong balls. There is, however, little flesh to eat, for they

are mostly juice and seeds. Some are rather intensely flavored, sweet,

and occasionally leave a bitter aftertaste. The plant's advantages are

early fruiting, abundant yields, and fairly tough-skinned fruit.

Solanum tabanoense

is a rare plant found between 2,800 and 3,500 m in southern Colombia,

Ecuador, and Peru. The fruit has an appreciable amount of flesh and is

similar to the pepino in size and taste.

1

In Spanish, “pepino dulce” means “sweet cucumber.” Regrettably, the

shortened name “pepino” is becoming the common name for this fruit in

English, for in Spanish “pepino” refers only to the cucumber. This

fruit, however, is botanically related to tomatoes and is nothing like

a cucumber.

2 Cieza de León, the Spanish chronicler of

the Incas, related that "in truth, a man needs to eat many before he

loses his taste for them."

3 Any dessert-quality fruit should be sweet, with Brix levels above 8—preferably 12 or even more. Information from S. Dawes.

4

Pepinos are easily propagated by seed, but usually the seedlings are

inferior to their parents. Seedlings, however, normally differ widely

from each other, which allows breeders to search for superior new

strains.

5 Hermann, 1988.

6 Tomatoes grown with saline irrigation have become a premium export of Israel because of their tangy taste.

7 Recent studies show that even immature seed is viable if germinated in nutrient agar. Information from J.R. Martineau.

|