Naranjilla (Lulo)

For centuries the naranjilla (Solanum quitoense)

has been an immensely popular fruit of Colombia and Ecuador. Writers

have described it as “the golden fruit of the Andes” and “the nectar of

the gods.”

Orange-yellow on the outside, 1 the fruits look somewhat

like tomatoes on the inside, but their pulp is green. Their juice,

considered the best in the region, is used to flavor drinks. 2 In fact, many even prefer it to orange juice.

Although

little known to the outside world, naranjilla (usually pronounced

na-ran-hee-ya in English) appears likely to produce a new taste for the

world's tables. It promises to become a new tropical flavor with a

potential at least as great as the increasingly popular passionfruit.

However,

producing naranjilla is a scientific challenge; before it can achieve

its potential, it needs intensive research. Despite its overwhelming

popularity in the northern Andes, it has been given little serious

commercial development. In fact, owing to several factors, naranjilla

fruits have become scarce and expensive in Ecuadorian and other Andean

markets. 3 Through misfortune and lack of funds, efforts to

check the devastation of nematode pests have failed so that production

in some areas is declining. On the other hand, demand is higher than

ever, owing to naranjilla's local popularity and the increasing export

of both fresh fruits and canned products.

Given attention, problems

such as these should be entirely avoidable, but even when such

operational difficulties are overcome, naranjilla will still be a

challenge to produce. It has little genetic diversity and,

consequently, is probably restricted to a narrow range of habitats. It

almost certainly requires a cool, moist environment—a type that is of

limited occurrence. It may also require a specialized pollinator.

Nonetheless,

with study, these problems can probably be overcome, or at least

mitigated. Then the taste of naranjilla should become known to millions.

PROSPECTS

The Andes.

Although now in decline, the naranjilla could become one of the major

horticultural products of the region and an important market crop for

small-scale producers. The fruit or juice (canned, frozen, or

concentrated) has considerable export potential. 4 What is needed is a coordinated effort to fully understand the crop's status and difficulties.

Nematocides

and biological controls are currently available to forestall the

devastation caused by root-knot nematodes. In addition, at least two

closely related species, apparently highly resistant to the root-knot

nematode, seem promising as rootstocks. They may also be sources of

genetic resistance, for they form fertile hybrids with naranjilla.

Other Developing Areas.

With the increasing international demand for exotic fruits, this is a

budding crop for the uplands of Central America and for other areas of

similar climate. Already, naranjilla has been established as a

small-scale crop in Panama, Costa Rica, and Guatemala. Both there and

in other frost-free, subtropical sites, it promises to become a

substantial resource. However, because of the plant's restrictive

climatic and agronomic requirements, success will not be achieved

easily. Establishing naranjilla in commercial production will require

much work and dedication.

Industrialized Regions.

Naranjilla can provide the basis for a new fruit- drink flavor that

could become popular in North America, Japan, Europe, and other such

areas. In a test at Cornell University several years ago, blindfolded

panelists unfamiliar with the fruit chose naranjilla juice over apple

juice by three to one, and a blend of naranjilla and apple juice over

apple juice alone by nine to one. In the 1970s, a major U.S. soup

manufacturer created a fruit drink based on naranjilla for nationwide

sale, but it reluctantly abandoned the project because of problems in

producing a large and reliable supply of fruit.

Pasto, Colombia. Naranjilla is among the most popular

fruits in the northern Andes.

USES

The naranjilla is versatile. It can be eaten raw or cooked

or used to make juice. It is also cooked in fruit pies and confections,

and is used to make jellies, jams, and other preserves. In Venezuela,

Panama, Costa Rica, and Guatemala, unstrained pulp is used for toppings

on cheesecakes, sponges, ice cream, yoghurt, and fruit salads. The

fresh juice is also processed into frozen concentrate and can be

fermented to make wine.

Despite its versatility, naranjilla is

mainly used at present to flavor drinks. In Ecuador and Colombia,

naranjilla sorbete is something of a national drink, often served in

hotels and restaurants. It is made like lemonade: the freshly extracted

juice is beaten with sugar into a foamy liquid that is green,

heavy-bodied, and sweet-sour in flavor. (Most tasters express surprise

that it is not a blend of several fruits.)

Naranjillas are eaten

only when fully ripe, at which time they yield to a soft squeeze and

their rather leathery skin is bright orange or yellow (though sometimes

still marbled with green). On average, they are about the size of golf

balls. The slightly acid flavor is more pronounced if the fruit is not

completely ripe. However, even some ripe fruits are too acid to be

eaten raw, and the pulp must be sweetened to be palatable.

Naranjilla fruit on a plant growing near Versailles,

Colombia.

NUTRITION

The naranjilla is rich in vitamins, proteins, and minerals. 5 It is said to contain pepsin, the stomach enzyme that aids digestion of proteins.

AGRONOMY

The

plant is propagated by seeds, cuttings, or grafts onto the rootstock of

other species. Seeds germinate freely. Cuttings root easily, especially

when parts of older, slightly woody stems are used. Like many members

of the Solanaceae, it can also be regenerated in tissue culture from

pieces of leaf or stem tissue.

The plant grows rapidly. Seedlings

begin bearing in 6–12 months; grafted plants mature even faster,

flowering at 3–4 months of age and maturing fruits at 6 months. In

principle, this perennial could continue bearing for years, but in the

Andes and Central America plantings usually succumb to root-knot

nematodes after about 4 years.

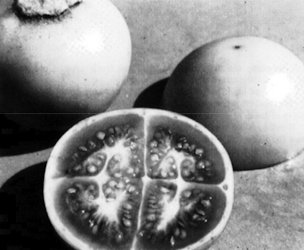

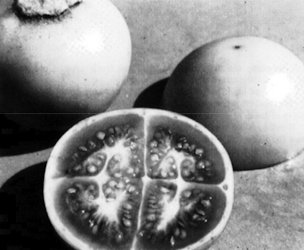

| Naranjilla

fruits look something like tomatoes, but they have yellow skin and

green flesh. Their greenish juice provides one of the culinary delights

of Colombia,

Ecuador, and Venezuela. |

Naranjilla

is a “heavy feeder” and responds well to fertilization. Pruning old

woody stems at the end of a fruiting cycle results in vigorous regrowth

and prevents fruit size from diminishing.

Andean farmers mainly grow

naranjilla on rainy slopes, where, as long as temperatures remain

moderate, fruits are produced year-round. To prevent fungal and

bacterial root infections, well-drained soils are imperative. A common

practice is to plant naranjilla in openings in the forest or to

interplant it with banana, tamarillo, or achira. The taller plants help

protect the naranjilla's brittle branches from wind damage. 6

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

The

fruits are closely borne in the axils of the leaves on stems and

branches. They are easy to pull off by hand and are normally picked

when about half ripe —that is, when they have started to color. (They

subsequently ripen normally.) The stiff hairs can irritate the skin, so

the fruits are handled with gloves until ripe enough for the fuzz to be

wiped off with a towel.

The picked fruits have a shelf life of up to

two weeks without refrigeration, making naranjilla an ideal truck crop.

Cold storage lengthens the storage period considerably.

Yields are

high. Individual plants may produce up to 10 kg of fruit a year, and on

a per-hectare basis may yield 27 tons of fruit or 47,000 liters of

juice.

If not handled correctly, much of the flavor can be lost in

canning and the juice can turn muddy looking. Proper cooling, storage,

and the use of antioxidants are necessary.

LIMITATIONS

Naranjilla's

major problems have already been discussed. They are its climatic

restrictions and susceptibility to pests. More information is given

below.

Adaptability This

plant has received little attention from horticultural researchers; its

environmental adaptations, therefore, are not well known, but seem to

be narrow. It is possible that it needs a long growing season, as well

as high humidity. It cannot tolerate frost. Heat and dryness can also

cause crop failure.

Moreover, there are possible pollination

problems. Naranjilla appears to be a short-day plant; pollen abortion

occurs when days are long. 7 Pollinators may be absent in

locations outside its native range. The effects of shade and altitude

are also uncertain. The plant is said to perform poorly under 1,200 m

elevation in the Andes.

Pests and Diseases As noted, the plant is extremely susceptible to root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne

species). Plantings often fail to reach full fruiting size as a result.

The naranjilla also suffers from insect pests; in particular, a wide

variety of coleopterans (beetles and weevils) chew the leaves.

The

plants can succumb to diseases such as bacterial wilt and fungal

infections. Root and stem rots can be particularly severe. Viruses,

too, can be troublesome.

RESEARCH NEEDS

Germplasm Collection Replicate germplasm collections should be established in Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, Costa Rica, and other countries.

A

germplasm collection of 185 samples is already being evaluated at the

Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA) in Colombia. 8

Nematodes

The nematode problem is the major one to be addressed. As a starter,

nematologists should determine the varieties of the offending pests.

Also, the relation between nematode resistance and temperature should

be checked. (Recent research has shown that nematode-resistant tomatoes

become susceptible as temperature rises.)

Although nematode-killing

chemicals can be used to treat the soil, these tend to

be toxic and expensive. An alternative approach could be biological

control. 9 Screening for strains resistant to nematodes

(and viruses) seems promising as well, although development of

horticulturally viable types could take years.

Alternative approaches include the following:

• Hybridizing naranjilla with closely related, nematode-resistant species. Hybrids with Solanum hirtum and S. macranthum,

for example, have good nematode resistance. Backcrossing these to

naranjilla has produced a range of plants that have shown resistance

and have borne fairly good fruit. 10

• Grafting naranjilla on related plants with nematode-resistant rootstock.

When cleft grafted on species such as S. macranthum and S. mammosum,

naranjilla plants have survived for about three years and fruited

successfully. In tropical Africa, naranjilla has done well when grafted

to its nematode-resistant local relative, S. torum. 11

• Improving plant vigor by better management.

• Producing the crop in beds of sterilized soil.

•

Growing a cover crop or rotation crop of plants, such as velvet bean or

Indigofera species, that help eliminate nematode infestations.

• Inducing somaclonal variation in regenerated plants as a way of unmasking inherent nematode resistance that is now hidden.

•

Educating farmers about nematodes and the means of keeping sites free

of infestation. (This is important, whatever other approach may be

used.)

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name Solanum quitoense Lamarck

Family Solanaceae (nightshade family)

Synonyms Solanum hirsutissimum; Solanum angulatum

Common Names

Quechua: lulo, lulu puscolulu

Spanish: naranjilla, naranjillo; naranjilla de Quito, naranjita, lulo, lullo, toronja, tomate chileno (Peru)

English: Quito orange, naranjilla, lulo

French: naranjille, morelle de Quito, orange de Quito

German: Lulo-Frucht

Origin.

Naranjilla's origin is unknown. Its wild progenitor may yet be

discovered—probably in Colombia. It is thought that the plant was

domesticated within the last few hundred years, because there is no

evidence that it was cultivated in pre-Columbian times. The first

records of naranjilla cultivation are from the mid–1600s in Ecuador and

Colombia. Traditionally, areas of major cultivation have been the

valleys of Pastaza and Yunguillas in Ecuador and the mountain areas of

Cauca and Nariño in Colombia.

Description.

The plant is a perennial, herbaceous shrub, 1–1.5 m high, with stout,

spreading, brittle stems. Its dark-green, purple or white-veined

leaves are often more than 30 cm long and, like the stems, are densely

pubescent. The pale lilac flowers are covered with a thick “felt” of

light-purple hairs.

The spherical, yellow-orange fruit is 3–8 cm in

diameter. It has a leathery skin, densely covered with fine, brittle,

easily removed, white to brown hairs. Internally, its structure

resembles a tomato. The acidulous, yellow-green flesh contains a

greenish pulp with numerous seeds and green-colored juice.

Horticultural Varieties.

On the whole, the species is unusually uniform for a cultivated plant.

However, two geographically separated varieties are recognized. Variety

quitoense is the common, spineless form found in southern Colombia and Ecuador. Variety septentrionale has spines, is hardier, and grows mainly at altitudes of 1,000–1,900 m in central Colombia and Costa Rica.

In

the last few years, an apparently new variety has appeared in Quito

markets. Although the fruits are smaller than normal, they are rapidly

becoming the dominant commercial type. 12 Investigation of

this may help open a new era in naranjilla use. Is this a new hybrid?

Is it being grown because of greater nematode resistance? Or is the

fact that its fruits have few hairs the driving force behind its

production?

Environmental Requirements

Daylength.

As noted, the plant seems to require short days for pollination.

However, this is not certain because satisfactory fruit set has been

noted in south Florida at any time of year. 13

Rainfall.

Naranjilla requires considerable moisture. It is commercially grown in

the Andean areas where annual rainfall is 1,500–3,750 mm. The lower

moisture limits are uncertain, but even moderately dry conditions check

its growth.

Altitude. This

is not a restriction. Samples have been collected near 2,000 m

elevation in Ecuador, and the plant grows near sea level in New Zealand

and California.

Low Temperature. Below 10°C the plant's growth is severely checked. It is frost sensitive.

High Temperature.

Above 30°C the plant grows poorly. It does not set fruit in areas with

high night temperature—a possible reason why it has failed in some

lowland tropical and subtropical areas.

Soil Type.

In Ecuador, the naranjilla grows best on fertile, well-drained slopes.

It requires soils that hold moisture but that drain well enough to

avoid waterlogging. It seems particularly sensitive to salt. 14

Related Species.

Naranjilla has several relatives that produce desirable fruits and

deserve more attention. They could be useful in their own right as well

as perhaps for genetically improving naranjilla. 15

Solanum pectinatum

This plant, although undomesticated, produces high quality fruits,

almost as good as those of the naranjilla. Compared with the

naranjilla, the fruits are slightly smaller, but their hairs rub off

more readily, and they taste somewhat sweeter. This is a lowland

species, widely distributed from Peru to southern Mexico, and from sea

level to 1500 m. Throughout the region, people gather the wild fruits

for making juice. It, too, deserves wider appreciation; a little

horticultural investigation might produce a new crop as popular as the

naranjilla, but suitable for cultivation in areas too warm for

naranjilla.

Solanum vestissimum

Native to Colombia and Venezuela, this is another wild species with

pleasantly flavored fruits. It grows at higher altitudes than

naranjilla. Known as “lulo de la tierra fria” (naranjilla of the cold

lands), toronja, or tumo, it is a small tree that bears fruit about the

size of duck eggs. The chief objection is that the fruit's hairs are

quite bristly and the juice is difficult to extract. For all that,

however, it has an excellent flavor and deserves research attention.

1

Although “naranjilla” is Spanish for “little orange,” the fruit is not

a citrus, but is a relative of the tomato and potato. In many areas it

is called “lulo,” a pre-Columbian word, possibly of Quechua origin.

2

In the 1760s, the Majorcan missionary Juan de Santa Gertrudis Serra

wrote of the naranjilla: The fruit is very fresh [and diluted] in

water with sugar, makes a refreshing drink of which I may say that it

is the most delicious that I have tasted in the world.

3 In the last decade, prices have increased more than tenfold (even accounting for inflation).

4 Colombia is already exporting small amounts to Central America and the United States.

5

The composition per 100 g edible portion: calories, 23; water, 92.5 g;

protein, 0.6 g; fat, 0.1 g; carbohydrates, 5.7 g; fiber, 0.3 g; ash,

0.8 g; calcium, 8 mg; phosphorus, 12 mg; vitamin A, 600 Int. units;

thiamine, 0.04 mg; riboflavin, 0.04 mg; niacin, 1.5 mg; ascorbic acid,

25 mg. Information from J. Morton.

6 It has been

suggested that on a commercial scale, the naranjilla could be

interplanted between babaco, mandarin orange, passionfruit (on wire

lattices), or other crop with the naranjilla's climatic requirements.

Suggestion from D. Endt.

7 Information from J. Soria.

8 Information from L.E. Lopez J.

9 For example, the bacterium Pasteuria penetrans

has proved as effective as current nematocides on other crops in

Britain. Spores can be produced in vivo on nematodes in roots, without

the necessity of sterile production systems. Information from B.R.

Kerry.

10 Information from L.E. Lopez J.

11

Both hybridizing and grafting also bestow resistance to root and collar

rot. However, further evaluation is needed to ensure that alkaloids in

the fruits do not rise to hazardous levels. Information from J. Soria.

12 Information from L.E. Lopez J.

13 Information from J. Morton.

14 Information from L. Davidson.

15 Information in this section is mainly from C. Heiser.

|