From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Mango

Mangifera

indica L.

ANACARDIACEAE

It is a matter of astonishment to many that the luscious mango, Mangifera indica

L., one of the most celebrated of tropical fruits, is a member of the

family Anacardiaceae–notorious for embracing a number of highly

poisonous plants. The extent to which the mango tree shares some of the

characteristics of its relatives will be explained further on. The

universality of its renown is attested by the wide usage of the name,

mango in English and Spanish and, with only slight variations in French

(mangot, mangue, manguier), Portuguese (manga, mangueira), and Dutch

(manja). In some parts, of Africa, it is called mangou, or mangoro.

There are dissimilar terms only in certain tribal dialects.

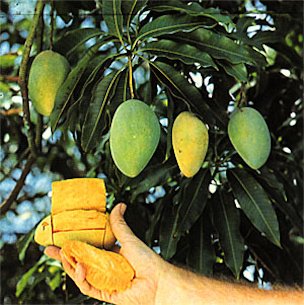

Plate XXVII: MANGO, Mangifera

indica–'Cambodiana'

Description

The

mango tree is erect, 30 to 100 ft (roughly 10-30 m) high, with a broad,

rounded canopy which may, with age, attain 100 to 125 ft (30-38 m) in

width, or a more upright, oval, relatively slender crown. In deep soil,

the taproot descends to a depth of 20 ft (6 in), the profuse,

wide-spreading, feeder root system also sends down many anchor roots

which penetrate for several feet. The tree is long-lived, some

specimens being known to be 300 years old and still fruiting.

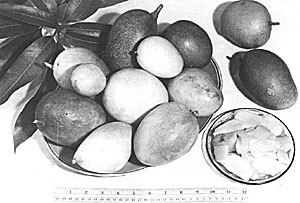

Plate XXVIII: MANGO, Mangifera

indica–'Kent', 'Tommy Atkins', and 'Irwin'

Nearly

evergreen, alternate leaves are borne mainly in rosettes at the tips of

the branches and numerous twigs from which they droop like ribbons on

slender petioles 1 to 4 in (2.5-10 cm) long. The new leaves, appearing

periodically and irregularly on a few branches at a time, are

yellowish, pink, deep-rose or wine-red, becoming dark-green and glossy

above, lighter beneath. The midrib is pale and conspicuous and the many

horizontal veins distinct. Full-grown leaves may be 4 to 12.5 in (10-32

cm) long and 3/4 to 2 1/8 in (2-5.4 cm) wide. Hundreds and even as many

as 3,000 to 4,000 small, yellowish or reddish flowers, 25% to 98% male,

the rest hermaphroditic, are borne in profuse, showy, erect, pyramidal,

branched clusters 2 1/2 to 15 1/2 in (6-40 cm) high. There is great

variation in the form, size, color and quality of the fruits. They may

be nearly round, oval, ovoid-oblong, or somewhat kidney-shaped, often

with a break at the apex, and are usually more or less lop-sided. They

range from 2 1/2 to 10 in (6.25-25 cm) in length and from a few ounces

to 4 to 5 lbs (1.8-2.26 kg). The skin is leathery, waxy, smooth, fairly

thick, aromatic and ranges from light-or dark-green to clear yellow,

yellow-orange, yellow and reddish-pink, or more or less blushed with

bright-or dark-red or purple-red, with fine yellow, greenish or reddish

dots, and thin or thick whitish, gray or purplish bloom, when fully

ripe. Some have a "turpentine" odor and flavor, while others are richly

and pleasantly fragrant. The flesh ranges from pale-yellow to

deep-orange. It is essentially peach-like but much more fibrous (in

some seedlings excessively so-actually "stringy"); is extremely juicy,

with a flavor range from very sweet to subacid to tart.

There is

a single, longitudinally ribbed, pale yellowish-white, somewhat woody

stone, flattened, oval or kidney-shaped, sometimes rather elongated. It

may have along one side a beard of short or long fibers clinging to the

flesh cavity, or it may be nearly fiberless and free. Within the stone

is the starchy seed, monoembryonic (usually single-sprouting) or

polyembryonic (usually producing more than one seedling).

Origin and

Distribution

Native

to southern Asia, especially eastern India, Burma, and the Andaman

Islands, the mango has been cultivated, praised and even revered in its

homeland since Ancient times. Buddhist monks are believed to have taken

the mango on voyages to Malaya and eastern Asia in the 4th and 5th

Centuries B.C. The Persians are said to have carried it to East Africa

about the 10th Century A.D. It was commonly grown in the East Indies

before the earliest visits of the Portuguese who apparently introduced

it to West Africa early in the 16th Century and also into Brazil. After

becoming established in Brazil, the mango was carried to the West

Indies, being first planted in Barbados about 1742 and later in the

Dominican Republic. It reached Jamaica about 1782 and, early in the

19th Century, reached Mexico from the Philippines and the West Indies.

In

1833, Dr. Henry Perrine shipped seedling mango plants from Yucatan to

Cape Sable at the southern tip of mainland Florida but these died after

he was killed by Indians. Seeds were imported into Miami from the West

Indies by a Dr. Fletcher in 1862 or 1863. From these, two trees grew to

large size and one was still fruiting in 1910 and is believed to have

been the parent of the 'No. 11' which was commonly planted for many

years thereafter.

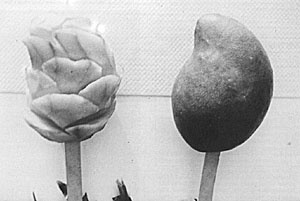

Fig. 59: Some mangoes (Mangifera

indica) more or less commonly grown in dooryards of

southern Florida in the mid-1940's.

In 1868 or 1869, seeds were planted south of Coconut

Grove and the resultant trees prospered at least until 1909, producing

the so-called 'Peach' or 'Turpentine' mango which became fairly common.

In 1872, a seedling of 'No. 11' from Cuba was planted in Bradenton. In

1877 and 1879, W.P. Neeld made successful plantings on the west coast

but these and most others north of Ft. Myers were killed in the January

freeze of 1886.

In 1885, seeds of the excellent 'Bombay' mango

of India were brought from Key West to Miami and resulted in two trees

which flourished until 1909. Plants of grafted varieties were brought

in from India by a west coast resident, Rev. D.G. Watt, in 1885 but

only two survived the trip and they were soon frozen in a cold spell.

Another unsuccessful importation of inarched trees from Calcutta was

made in 1888. Of six grafted trees that arrived from Bombay in 1889,

through the efforts of the United States Department of Agriculture,

only one lived to fruit nine years later. The tree shipped is believed

to have been a 'Mulgoa' (erroneously labeled 'Mulgoba', a name unknown

in India except as originating in Florida). However, the fruit produced

did not correspond to 'Mulgoa' descriptions. It was beautiful,

crimson-blushed, just under 1 lb (454 g) with golden-yellow flesh. No

Indian visitor has recognized it as matching any Indian variety. Some

suggest that it was the fruit of the rootstock if the scion had been

frozen in the freeze of 1894-95. At any rate, it continued to be known

as 'Mulgoba', and it fostered many off-spring along the southeastern

coast of the State and in Cuba and Puerto Rico, though it proved to be

very susceptible to the disease, anthracnose, in this climate. Seeds

from this tree were obtained and planted by a Captain Haden in Miami.

The trees fruited some years after his death and his widow gave the

name 'Haden' to the tree that bore the best fruit. This variety was

regarded as the standard of excellence locally for many decades

thereafter and was popular for shipping because of its tough skin.

George

B. Cellon started extensive vegetative propagation (patch-budding) of

the 'Haden' in 1900 and shipped the fruits to northern markets. P.J.

Wester conducted many experiments in budding, grafting and inarching

from 1904 to 1908 with less success. Shield-budding on a commercial

scale was achieved by Mr. Orange Pound of Coconut Grove in 1909 and

this was a pioneer breakthrough which gave strong impetus to mango

growing, breeding, and dissemination.

Enthusiastic

introduction of other varieties by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's

Bureau of Plant Industry, by nurserymen, and other individuals

followed, and the mango grew steadily in popularity and importance. The

Reasoner Brothers Nursery, on the west coast, imported many mango

varieties and was largely responsible for the ultimate establishment of

the mango in that area, together with a Mr. J.W. Barney of Palma Sola

who had a large collection of varieties and had worked out a feasible

technique of propagation which he called "slot grafting".

Dr.

Wilson Popenoe, one of the early Plant Explorers of the U.S. Department

of Agriculture, became Director of the Escuela Agricola Panamericana,

Tegucigalpa, Honduras. For more than a quarter of a century, he was a

leader in the introduction and propagation of outstanding mangos from

India and the East Indies, had them planted at the school and at the

Lancetilla Experiment Station at Tela, Honduras, and distributed around

tropical America.

In time, the mango became one of the most

familiar domesticated trees in dooryards or in small or large

commercial plantings throughout the humid and semi-arid lowlands of the

tropical world and in certain areas of the near-tropics such as the

Mediterranean area (Madeira and the Canary Islands), Egypt, southern

Africa, and southern Florida. Local markets throughout its range are

heaped high with the fragrant fruits in season and large quantities are

exported to non-producing countries.

Altogether, the U.S.

Department of Agriculture made 528 introductions from India, the

Philippines, the West Indies and other sources from 1899 to 1937.

Selection, naming and propagation of new varieties by government

agencies and individual growers has been going on ever since. The Mango

Form was created in 1938 through the joint efforts of the Broward

County Home Demonstration Office of the University of Florida's

Cooperative Extension Service and the Fort Lauderdale Garden Club, with

encouragement and direction from the University of Florida's

Subtropical Experiment Station (now the Agricultural Research and

Education Center) in Homestead, and Mrs. William J. Krome, a pioneer

tropical fruit grower. Meetings were held annually, whenever possible,

for the exhibiting and judging of promising seedlings, and exchanging

and publication of descriptions and cultural information.

Meanwhile,

a reverse flow of varieties was going on. Improved mangos developed in

Florida have been of great value in upgrading the mango industry in

tropical America and elsewhere.

With such intense interest in

this crop, mango acreage advanced in Florida despite occasional

setbacks from cold spells and hurricanes. But with the expanding

population, increased land values and cost and shortage of agricultural

labor after World War II, a number of large groves were subdivided into

real estate developments given names such as "Mango Heights" and "Mango

Terrace". There were estimated to be 7,000 acres (2,917 ha) in 27

Florida counties in 1954, over half in commercial groves. There were

4,000 acres (1,619 ha) in 1961. Today, mango production in Florida, on

approximately 1,700 acres (688 ha), is about 8,818 tons (8,000 MT)

annually in "good" years, and valued at $3 million. Fruits are shipped

not only to northern markets but also to the United Kingdom,

Netherlands, France and Saudi Arabia. In advance of the local season,

quantities are imported into the USA from Haiti and the Dominican

Republic, and, throughout the summer, Mexican sources supply mangos to

the Pacific Coast consumer. Supplies also come in from India and Taiwan.

A

mango seed from Guatemala was planted in California about 1880 and a

few trees have borne fruit in the warmest locations of that state, with

careful protection when extremely low temperatures occur.

Mangos

have been grown in Puerto Rico since about 1750 but mostly of

indifferent quality. A program of mango improvement began in 1948 with

the introduction and testing of over 150 superior cultivars by the

University of Puerto Rico. The south coast of the island, having a dry

atmosphere, is best suited for mango culture and substantial quantities

of mangos are produced there without the need to spray for anthracnose

control. The fruits are plentiful on local markets and shipments are

made to New York City where there are many Puerto Rican residents. A

study of 16 cultivars was undertaken in 1960 to determine those best

suited to more intense commercial production. Productivity evaluations

started in 1965 and continued to 1972.

The earliest

record of the mango in Hawaii is the introduction of several small

plants from Manila in 1824. Three plants were brought from Chile in

1825. In 1899, grafted trees of a number of Indian varieties, including

'Pairi', were imported. Seedlings became widely distributed over the

six major islands. In 1930, the 'Haden' was introduced from Florida and

became established in commercial plantations. The local industry began

to develop seriously after the importation of a series of monoembryonic

cultivars from Florida. But Hawaiian mangos are prohibited from entry

into mainland USA, Australia, Japan and some other countries, because

of the prevalence of the mango seed weevil in the islands.

In

Brazil, most mangos are produced in the state of Minas, Gerais where

the crop amounts to 243,018 tons (22,000 MT) annually on 24,710 acres

(10,000 ha). These are mainly seedlings, as are those of the other

states with major mango crops–Ceará, Paraibá,

Goias, Pernambuco, and Maranhao. Sao Paulo raises about 63,382 tons

(57,500 MT) per year on 9,884 acres (4,000 ha). The bulk of the crop is

for domestic consumption. In 1973, Brazil exported 47.4 tons (43 MT) of

mangos to Europe.

Mango growing began with the earliest settlers

in North Queensland, Australia, with seeds brought casually from India,

Ceylon, the East Indies and the Philippines. In 1875, 40 varieties from

India were set out in a single plantation. Over the years, selections

have been made for commercial production and culture has extended to

subtropical Western Australia.

There is no record of the

introduction of the mango into South Africa but a plantation was set

out in Durban about 1860. Production today probably has reached about

16,535 tons (15,000 MT) annually, and South Africa exports fresh mangos

by air to Europe.

Kenya exports mature mangos to France and Germany

and both mature and immature to the United Kingdom, the latter for

chutney-making. Egypt produces 110,230 tons (100,000 MT) of mangos

annually and exports moderate amounts to 20 countries in the Near East

and Europe. Mango culture in the Sudan occupies about 24,710 acres

(10,000 ha) producing a total of 66,138 tons (60,000 MT) per year.

India,

with 2,471,000 acres (1,000,000 ha) of mangos (70% of its fruit-growing

area) produces 65% of the world's mango crop–9,920,700 tons

(9,000,000 MT). In 1985, mango growers around Hyderabad sought

government protection against terrorists who cut down mango orchards

unless the owners paid ransom (50,000 rupees in one case). India far

outranks all other countries as an exporter of processed mangos,

shipping 2/3 of the total 22,046 tons (20,000 MT). Mango preserves go

to the same countries receiving the fresh fruit and also to Hong Kong,

Iraq, Canada and the United States. Following India in volume of

exports are Thailand, 774,365 tons (702,500 MT), Pakistan and

Bangladesh, followed by Brazil. Mexico ranks 5th with about 100,800

acres (42,000 ha) and an annual yield of approximately 640,000 tons

(580,000 MT). The Philippines have risen to 6th place. Tanzania is 7th,

the Dominican Republic, 8th and Colombia, 9th.

Leading exporters

of fresh mangos are: the Philippines, shipping to Hong Kong, Singapore

and Japan; Thailand, shipping to Singapore and Malaysia; Mexico,

shipping mostly 'Haden' to the United States, 2,204 tons (2,000 MT),

annually, also to Japan and Paris; India, shipping mainly 'Alphonso'

and 'Bombay' to Europe, Malaya, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait; Indonesia,

shipping to Hong Kong and Singapore; and South Africa shipping (60%

'Haden' and 'Kent') by air to Europe and London in mid-winter.

Chief

importers are England and France, absorbing 82% of all mango shipments.

Mango consumers in England are mostly residents of Indian origin, or

English people who formerly lived in India.

The first

International Symposium on Mango and Mango Culture, of the

International Society for Horticultural Science, was held in New Delhi,

India, in 1969 with a view to assembling a collection of germplasm from

around the world and encouraging cooperative research on rootstocks and

bearing behavior, hybridization, disease, storage and transport

problems, and other areas of study.

Varieties

The

original wild mangos were small fruits with scant, fibrous flesh, and

it is believed that natural hybridization has taken place between M.

indica and M. sylvatica Roxb. in Southeast Asia. Selection for higher

quality has been carried on for 4,000 to 6,000 years and vegetative

propagation for 400 years.

Over 500 named varieties (some say

1,000) have evolved and have been described in India. Perhaps some are

duplicates by different names, but at least 350 are propagated in

commercial nurseries. In 1949, K.C. Naik described 82 varieties grown

in South India. L.B. and R.N. Singh presented and illustrated 150 in

their monograph on the mangos of Uttar Pradesh (1956). In 1958, 24 were

described as among the important commercial types in India as a whole,

though in the various climatic zones other cultivars may be prominent

locally. Of the 24, the majority are classed as early or mid-season:

Early:

'Bombay Yellow'

('Bombai')–high quality

'Malda'

('Bombay Green')

'01our'

(polyembryonic)–a heavy bearer.

'Pairi'

('Paheri', 'Pirie', 'Peter', 'Nadusalai', 'grape', 'Raspuri', 'Goha

bunder')

'Safdar Pasand'

'Suvarnarekha'

('Sundri')

Early to Mid-Season:

'Langra'

'Rajapuri'

Mid-Season:

'Alampur Baneshan'–high

quality but shy bearer

'Alphonso'

('Badami', 'gundu', 'appas', 'khader')–high quality

'Bangalora'('Totapuri',

'collection', 'kili-mukku', abu Samada' in the Sudan)–of highest

quality, best keeping, regular bearer, but most susceptible to seed

weevil.

'Banganapally'

('Baneshan', 'chaptai', 'Safeda')–of high quality but shy bearer

'Dusehri'

('Dashehari aman', 'nirali aman', 'kamyab')–high quality

'Gulab Khas'

'Zardalu'

'K.O. 11'

Mid- to Late-Season:

'Rumani'

(often bearing an off-season crop)

'Samarbehist'

('Chowsa', 'Chausa', 'Khajri')–high quality

'Vanraj'

'K.O. 7/5'

('Himayuddin' ´ 'Neelum')

Late:

'Fazli'

('Fazli malda')–high quality

'Safeda Lucknow'

Often Late:

'Mulgoa'–high

quality but a shy bearer

'Neelum'

(sometimes twice a year)–somewhat dwarf, of indifferent quality, and

anthracnose-susceptible.

Most

of the leading Indian cultivars are seedling selections. Over 50,000

crosses were made over a period of 20 years in India and 750 hybrids

were raised and screened. Of these, 'Mallika',

a cross of 'Neelum'

(female parent) with 'Dashehari'

(male parent) was released for cultivation in 1972. The hybrid tends

toward regular bearing, the fruits are showier and are thicker of flesh

than either parent, the flavor is superior and keeping quality better.

The season is nearly a month later than 'Dashehari'. Another

new hybrid, 'Amrapali',

of which 'Dashehari' was the female parent and 'Neelum'

the male, is definitely dwarf, precocious, a regular and heavy bearer,

and late in the season. The fruit is only medium in size; flesh is rich

orange, fiberless, sweet and 2 to 3 times as high in carotene as either

parent.

The Central Food Technological Research Institute

Experiment Station in Hyderabad has evaluated 9 "table varieties"

(firm-fleshed), 4 "juicy" varieties, and 5 hybrids as to suitability

for processing. 'Baneshan',

'Suvarnarekha'

and '5/5 Rajapuri'

'Langra'

were deemed suitable for slicing and canning. 'Baneshan', 'Navaneetam', 'Goabunder', 'Royal Special', 'Hydersaheb' and '9/4 Neelum Baneshan',

for canned juice; and 'Baneshan',

'Navaneetam',

'Goabunder',

'K.O. 7'and 'Sharbatgadi' for

canned nectar.

It is interesting to note that all but four

of the leading Indian cultivars are yellow-skinned. The exceptions are:

two yellow with a red blush on shoulders, one red-yellow with a blush

of red, and one green. In Thailand, there is a popular mango called

'Tong dum' ('Black Gold') marketed when the skin is very dark-green and

usually displayed with the skin at the stem end cut into points and

spread outward to show the golden flesh in the manner that red radishes

are fashioned into "radish roses" in American culinary art.

European

consumers prefer a deep-yellow mango that develops a reddish-pink

tinge. In Florida, the color of the mango is an important factor and

everyone admires a handsome mango more or less generously overlaid with

red. Red skin is considered a necessity in mangos shipped to northern

markets, even though the quality may be inferior to that of non-showy

cultivars. Also, dependable bearing and shippability are rated above

internal qualities for practical reasons. And a shipping mango must be

one that can be picked 2 weeks before full maturity without appreciable

loss of flavor. Too, there must be several varieties to extend the

season over at least 3 months.

Florida

mangos are classed in 4 groups:

1–Indian

varieties, mainly monoembryonic, introduced in the past and maintained

mostly in collections; typically of somewhat "turpentine" character.

2–Philippine

and Indo-Chinese types, largely polyembryonic, non-turpentiney,

fiberless, fairly anthracnose-resistant. Scattered in dooryard

plantings.

3–West Indian/South American mangos, especially

'Turpentine' and 'No.11' and the superior 'Julie' from Trinidad,

'Madame Francis' from Haiti, 'Itamaraca' from Brazil. These are

non-commercial.

4–Florida-originated selections or cultivars, of which many have risen

and declined over the decades.

In

general, mangos from the Philippines ('Carabao') and Thailand

('Saigon', 'Cambodiana') behave better in Florida's humidity than the

Indian varieties.

The much-prized 'Haden' was being recognized

in the late 1930's and early 1940's as anthracnose-prone, a light and

irregular bearer, and was being replaced by more disease-resistant and

prolific cultivars. The present-day leaders for commercial production

and shipping are 'Tommy Atkins', 'Keitt', 'Kent', 'Van Dyke' and

Jubilee'. The first 2 represent 50% of the commercial crop.

'Tommy Atkins'

(from a seed planted early in the 1920's at Fort Lauderdale, Florida;

commercially adopted in the late 1950's); oblong-oval; medium to large;

skin thick, orange-yellow, largely overlaid with bright- to dark-red

and heavy purplish bloom, and dotted with many large, yellow-green

lenticels. Flesh medium- to dark-yellow, firm, juicy, with medium

fiber, of fair to good quality; flavor poor if over-fertilized and

irrigated. Seed small. Season: mid-May to early July, or late June

through July, depending on spring weather; can be picked early,

developing good color and usually has long shelf-life. Sometimes there

is an open space in the flesh at the stem-end. Interior softening near

the seed occurs in some years. Anthracnose-resistant.

'Keitt'–rounded-oval

to ovate; large; skin medium-thick, yellow with light-red blush and a

lavender bloom; the many lenticels small, yellow to red. Flesh

orange-yellow, firm, fiberless except near the seed; of rich, sweet

flavor; very good quality. Seed small, or medium to large. Season:

early July through August or August and September, depending on spring

weather. Tree small to medium, erect, open, rather scraggly but very

productive. For market acceptance, requires post-harvest ethylene

treatment to enhance color.

'Kent'–ovate,

thick; large; skin greenish-yellow with dark-red blush and gray bloom;

many small, yellow lenticels. Flesh fiberless, juicy, sweet; very good

to excellent. Seed small. Season: July and August and often into

September, but if left on too long the seed tends to sprout in the

fruit–a condition called ovipary. Subject to black spot. Tree is

of erect, slender habit, of moderate size, precocious; bears very well

and fruit ships well, but, for the market, needs ethylene treatment to

enrich color.

'Van Dyke'

and 'Jubilee'

are relatively new cultivars maturing from late June through July. 'Van

Dyke' is of superior color and excellent quality but subject to

anthracnose and may not hold its place for long.

Two cultivars that have stood the test of time and have been shipped

north on a lesser scale are:

'Sensation'

(originated in North Miami; tree moved to Carmichael grove near Perrine

and propagated and grown commercially since 1949). Oval, oblique, and

faintly beaked; medium to medium-small; skin thin, adherent; basically

yellow to yellow-orange overlaid with dark plum-red, and with tiny,

pale-yellow lenticels. Flesh pale-yellow, firm, with very little fiber,

faintly aromatic, of mild, slightly sweet flavor; of good quality.

Monoembryonic. Tree bears heavily in August.

'Palmer'–oblong-ovate,

plump; large; skin medium-thick, orange-yellow with red blush and pale

bloom and many large lenticels. Flesh dull-yellow, firm, with very

little or no fiber; of fair to good quality. Seed long, of medium size.

Season: July and August, sometimes into September. Tree is medium to

large; precocious; usually bears well.

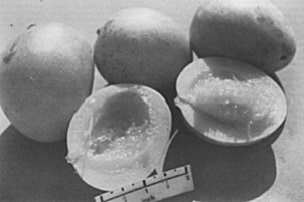

Fig. 60: The tiny, colorful 'Azucar' mango of Santa Marta and

Baranquilla, Colombia, is sweet and freestone.

The leading cultivar for local market at present is:

'Irwin'

(a seedling of 'Lippens', planted by F.D. Irwin of Miami in 1939; bore

its first fruits in 1945); oblong-ovate, one shoulder oblique; of

medium size; skin orange to pink with extensive dark-red blush and

small, white lenticels. Seed of medium size. Flesh yellow, almost

fiberless, with mild, sweet flavor; good to very good quality. Seed

small. Season: mid-May to early July; or June through July. Tree

somewhat dwarf; bears heavy crops of fruits in clusters. Fruit no

longer shipped because if picked before full maturity ripens with a

mottled appearance which is not acceptable on the market.

Non-colorful or not high-yielding cultivars of excellent quality

recommended for Florida homeowners include:

'Carrie'

(somewhat dwarf); 'Edward'

('Haden' seedling); 'Florigon';

'Jacquelin';

'Cambodiana';

'Cecil'; 'Saigon'.

Among cultivars formerly commercial but largely top-worked to others

favored for various reasons: 'Davis-Haden'

(a 'Haden' seedling); 'Fascell';

'Lippens' (a

'Haden' seedling); 'Smith'

(a 'Haden' seedling); 'Spring-fels';

'Dixon'; 'Sunset'; 'Zill' (a 'Haden'

seedling).

Many

cultivars that have lost popularity in Florida have become of

importance elsewhere. 'Sandersha', for example, has proved remarkably

resistant to most mango fruit diseases in South Africa.

The histories and descriptions of 46 cultivars growing in Brazil were

published in 1955. These included 'Brooks',

'Cacipura', 'Cambodiana', 'Goa-Alphonso', 'Haden', 'Mulgoba', 'Pairi', 'Pico', 'Sandersha', 'Singapore', 'White Langra', all

brought in from Florida. The rest are mostly local seedlings. 'Haden'

was introduced from Florida in 1931 and has been widely cultivated. It

is still included among the cultivars of major importance, the others

being 'Extrema',

'Non-Plus-Ultra'.

'Carlota';

but in 1977 the leading cultivar in Brazil was reported to be 'Bourbon', also known

as 'Espada'.

It is found especially in northeastern Brazil but is recommended for

all other mango areas. A collection of 53 cultivars is maintained at

Piricicaba and another of 82 at Bahia.

Of Mexican mangos, 65%

are Florida selections; 35% are of the type commonly grown in the

Philippines. Over a period of 3 years detailed studies have been made

of the commercial cultivars in Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico, with a view

to determining the most profitable for export. Results indicated that

propagation of 'Purple

Irwin', 'Red

Irwin', 'Sensation'

and 'Zill'

should be discontinued, and that 'Haden',

'Kent' and 'Keitt'

will continue to be planted, the first two because, of their color and

quality, and the third in spite of its deficiency in color.

'Manila', a

Philippine mango, early-ripening, is much grown in Veracruz. 'Manzanillo-Nunez',

a chance seedling first noticed in 1972, is gaining in popularity

because of its regular bearing, skin color (75% red), nearly fiberless

flesh, good quality, high yield and resistance to anthracnose.

'Julie'

is the main mango exported from the West Indies to Europe. The fruit is

somewhat flattened on one side, of medium size; the flesh is not

completely fiberless but is of good flavor. It came to Florida from

Trinidad but has long been popular in Jamaica. The tree is somewhat

dwarf, has 30% to 50% hermaphrodite flowers; bears well and regularly.

It is adaptable to humid environments and disease-resistant and the

fruit is resistant to the fruit fly. 'Julie' has been

grown in Ghana since the early 1920's. From 'Julie', the

well-known mango breeder, Lawrence Zill, developed 'Carrie', but

'Julie' has not been planted in Florida for many years.

Grafted

plants of the 'Bombay Green', so popular in Jamaica, were brought there

from India in 1869 by the then governor, Sir John Peter Grant, but were

planted in Castleton gardens where the trees flourished but failed to

fruit in the humid atmosphere. Years later, a Director of Agriculture

had budwood from these trees transferred to rootstocks at Hope Gardens.

The results were so successful that the 'Bombay Green' became

commonly planted on the island. The author brought six grafted trees

from Jamaica to Miami in 1951 and, after they were released from

quarantine, distributed them to the Subtropical Experiment Station in

Homestead, the Newcomb Nursery, and a private grower, but all succumbed

to the cold in succeeding winters. The fruit is completely fiberless

and freestone so that it is frequently served cut in half and eaten

with a spoon. The seed is pierced with a mango fork and served also so

that the luscious flesh that adheres to it may be enjoyed as well.

One

of the best-known mangos peculiar to the West Indies is 'Madame

Francis' which is produced abundantly in Haiti. It is a large,

flattened, kidney-shaped mango, light-green, slightly yellowish when

ripe, with orange, low-fiber, richly flavored flesh. This mango has

been regularly exported to Florida in late spring after fumigation

against the fruit fly.

Ghana received more than a

dozen cultivars back in the early 1920's. In 1973, it was found that

only three of these–'Julie', 'Jaffna' and 'Rupee'–could be

recognized with certainty. More than a dozen other cultivars were

brought in much later from Florida and India. An effort was begun in

1967 to classify the seedlings (from 10 to 50 years of age) in the

Ejura district, the Ejura Agricultural Station, and the plantation of

the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Science and Technology,

Kumasi, in order to eliminate confusion and have identifiable cultivars

marked for future research. After checking with available published

material on other cultivars for possible resemblances, descriptions and

photographs of 21 newly named cultivars were published in 1973. Of

these, 12 are fibrous and 9 fiberless. (See Godfrey-Sam-Aggrey and

Arbutiste in the Bibliography). One of the fibrous cultivars, named

'Tee-Vee-Dee', is so well flavored and aromatic that it is locally

extremely popular.

Until the mid-1960's mangos were grown only

in dooryards in Surinam and the few varieties were largely

polyembryonic types from Indonesia, and these have given rise to many

chance seedlings. In order to discover the best for commercial

planting, mango exhibits were sponsored and budwood of the best

selections has been grafted onto various rootstocks at the Paramaribo

Agricultural Experiment Station. The two most important local mangos

are:

'Golek'

(from Java;

also grown in Queensland) long-oblong; skin dull-green or

yellowish-green even when ripe, leathery; flesh pale yellow, thick,

fiberless, sweet, rich, of excellent quality. Keeps well in cold

storage for 3 weeks. Season: early (December in Queensland). Tree bears

moderately to heavily. This cultivar is considered the most promising

for large-scale culture and export. In Queensland it tends to crack

longitudinally as it matures.

'Roodborstje'–medium

to large; skin deep-red; flesh sweet, juicy, with very little fiber.

Not a good keeper. Season: early to midseason. Tree is a heavy bearer.

In

Venezuela, eleven cultivars were evaluated by food technologists for

processing suitability–'Blackman', 'Glenn', 'Irwin', 'Kent',

'Lippens', 'Martinica', 'Sensation', 'Smith', 'Selection 80',

'Selection 85', and 'Zill'. The most appropriate, because of

physicochemical characteristics and productivity were determined to be:

'Glenn', 'Irwin', 'Kent' and 'Zill'.

In Hawaii, 'Haden'

has represented 90% of all commercial production. 'Pairi' is more

prized for home use but is a shy bearer, a poor keeper, not as colorful

as 'Haden', so it never attained commercial status. In a search for

earlier and later varieties of commercial potential, over 125 varieties

were collected and tested between 1934 and 1969. In 1956, one of the

winning entries in a mango contest attracted much attention. After

propagation and due observation it was named 'Gouveia' in 1969 and

described as: ovate-oblong, of medium size, with medium-thick,

ochre-yellow skin blushed with blood-red over 2/3 of the surface. Flesh

is orange, nearly fiberless, sweet, juicy. Seed is small, slender,

monoembryonic. Season: late. Tree is of medium size, a consistent but

not heavy bearer. In quality tests 'Gouveia' received top scoring over

'Haden', 'Pairi', and several other cultivars. Florida mangos rated as

promising for Hawaii were 'Pope', 'Kent', 'Keitt' and 'Brooks' (later

than 'Haden') and 'Earlygold' and 'Zill' (earlier than 'Haden').

In Queensland, 'Kensington

Pride'

is the leading commercial cultivar in the drier areas. In humid regions

it is anthracnose-prone and requires spraying. It is thought to have

been introduced by traders in Bowen who were shipping horses for

military use in India. It may be called 'Kensington', 'Bowen', or,

because of its color, 'Apple' or 'Strawberry'. The fruit is distinctly

beaked when immature, with a groove extending from the stem to the

beak. It is medium-large; the skin is bright orange-yellow with

red-pink blush overlying areas exposed to the sun. Flesh is orange,

thick, nearly fiberless, juicy, of rich flavor. This cultivar is

classified as mid-season. The fruit matures from early to mid-November

at latitude 13°S; 6 weeks later at Bowen (20°S) and 1 week

later for each degree of latitude from Bowen to Brisbane. But at

17°S and an altitude of 1,148 ft (350 m) peak maturity is in mid-

to late-January. Polyembryonic. The fruit ships well but the tree is

not a dependable nor heavy bearer. It has an oval crown and unusually

sweet-scented leaves.

In 1981, after evaluating 43 accessions

seeking to lengthen the mango season in Queensland, 9 that mature

between 2 weeks earlier and 4 weeks later than 'Kensington Pride' were

chosen for commercial testing. Only one, 'Banana-1', was a Queensland

selection. The other 8 were introductions from Florida–'Smith',

'Palmer', 'Haden', 'Zill', 'Carrie', 'Irwin', 'Kent', 'Keitt'. 'Kent'

and 'Haden' have proved to be highly susceptible to blackspot in

Queensland; 'Keitt', 'Smith', and 'Zill' less so; and 'Palmer' and

'Kensington Pride' resistant.

In the Philippines, the 'Carabao'

constitutes 66% of the crop and 'Pico'

26%. These cultivars, apparently of Southeast Asian origin have

remained the most commonly grown and exported for many years.

In

Israel, 'Haden' has been popular for a long time though it is sensitive

to low temperatures in spring. An Egyptian introduction, 'Mabroka' is later in

season and escapes the early frosts. 'Maya', a local

seedling of 'Haden' has done well. Perhaps the most promising today is 'Nimrod',

a seedling of 'Maya', open pollinated, perhaps by 'Haden', planted in

1943, observed for 20 years and budded progeny for another 9 years;

named and released in 1970. The fruit is round-ovate, large; skin is

fairly thin, olive-green to yellow-green, blushed with red; attractive.

Flesh is deep-yellow, nearly fiberless, of fair flavor. Seed is large,

monoembryonic. Matures in mid-season (all August to mid-September in

Israel). Tree is large, upright, very cold-resistant. Average yield is

480 lbs (218 kg) per tree over 10 years.

It is impressive to see

how the early favorite, 'Haden', has influenced mango culture in many

parts of the world. Today, the Subtropical Horticulture Research Unit

of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Agricultural Research and

Education Center of the University of Florida, together maintain 125

mango cultivars as a resource for mango growers and breeders in many

countries.

Blooming and

Pollination

Mango

trees less than 10 years old may flower and fruit regularly every year.

Thereafter, most mangos tend toward alternate, or biennial, bearing. A

great deal of research has been done on this problem which may involve

the entire tree or only a portion of the branches. Branches that fruit

one year may rest the next, while branches on the other side of the

tree will bear.

Blooming is strongly affected by weather,

dryness stimulating flowering and rainy weather discouraging it. In

most of India, flowering occurs in December and January; in northern

India, in January and February or as late as March. There are some

varieties called "Baramasi" that flower and fruit irregularly

throughout the year. The cultivar 'Sam Ru Du' of Thailand bears 3 crops

a year–in January, June and October. In the drier islands of the

Lesser Antilles, there are mango trees that flower and fruit more or

less continuously all year around but never heavily at any time. Some

of these are cultivars introduced from Florida where they flower and

fruit only once a year. In southern Florida, mango trees begin to bloom

in late November and continue until February or March, inasmuch as

there are early, medium, and late varieties. During exceptionally warm

winters, mango trees have been known to bloom 3 times in succession,

each time setting and maturing fruit.

In the Philippines,

various methods are employed to promote flowering: smudging (smoking),

exposing the roots, pruning, girdling, withholding nitrogen and

irrigation, and even applying salt. In the West Indies, there is a

common folk practice of slashing the trunk with a machete to make the

tree bloom and bear in "off" years. Deblossoming (removing half the

flower clusters) in an "on" year will induce at least a small crop in

the next "off" year. Almost any treatment or condition that retards

vegetative growth will have this effect. Spraying with growth-retardant

chemicals has been tried, with inconsistent results. Potassium nitrate

has been effective in the Philippines.

In India, the

cultivar 'Dasheri', which is self incompatible, tends to begin blooming

very early (December and January) when no other cultivars are in

flower. And the early particles show a low percentage of hermaphrodite

flowers and a high incidence of floral malformation. Furthermore, early

blooms are often damaged by frost. It has been found that a single

mechanical deblossoming in the first bud-burst stage, induces

subsequent development of particles with less malformation, more

hermaphrodite flowers, and, as a result, a much higher yield of fruits.

There

is one cultivar, 'Neelum', in South India that bears heavily every

year, apparently because of its high rate (16%) of hermaphrodite

flowers. (The average for 'Alphonso' is 10%.) However, Indian

horticulturists report great tree-to-tree variation in seedlings of

this cultivar; in some surveys as much as 84% of the trees were rated

as poor bearers. Over 92% of 'Bangalora' seedlings have been found

bearing light crops.

Mango flowers are visited by fruit bats,

flies, wasps, wild bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, ants and various

bugs seeking the nectar and some transfer the pollen but a certain

amount of self-pollination also occurs. Honeybees do not especially

favor mango flowers and it has been found that effective pollination by

honeybees would require 3 to 6 colonies per acre (6-12 per ha). Many of

the unpollinated flowers are shed or fail to set fruit, or the fruit is

set but is shed when very young. Heavy rains wash off pollen and thus

prevent fruit setting. Some cultivars tend to produce a high percentage

of small fruits without a fully developed seed because of unfavorable

weather during the fruit-setting period.

Shy-bearing cultivars

of otherwise desirable characteristics are hybridized with heavy

bearers in order to obtain better crops. For example: shy-bearing

'Himayuddin', heavy-bearing 'Neelum'. Breeders usually hand-pollinate

all the flowers that are open in a cluster, remove the rest, and cover

the inflorescence with a plastic bag. But researchers in India have

found that there is very little chance of contamination and that

omitting the covering gives as much as 3.85% fruit set in place of

0.23% to 1.57% when bagged. Thus large populations of hybrids may be

raised for study. One of the latest techniques involves grafting the

male and female parents onto a chosen tree, then covering the panicles

with a polyethylene bag, and introducing house flies as pollinators.

Indian

scientists have found that pollen for crossbreeding can be stored at

32º F (0º C) for 10 hours. If not separated from the flowers,

it remains viable for 50 hours in a humid atmosphere at 65º to

75º F (18.33º -23.09º C). The stigma is receptive 18 hours

before full flower opening and, some say, for 72 hours after.

Climate

The

mango is naturally adapted to tropical lowlands between 25ºN and

25ºS of the Equator and up to elevations of 3,000 ft (915 m). It is

grown as a dooryard tree at slightly cooler altitudes but is apt to

suffer cold damage. The amount of rainfall is not as critical as when

it occurs. The best climate for mango has rainfall of 30 to 100 in

(75-250 cm) in the four summer months (June to September) followed by 8

months of dry season. This crop is well suited to irrigated regions

bordering the desert frontier in Egypt. Nevertheless, the tree

flourishes in southern Florida's approximately 5 months of

intermittent, scattered rains (October to February), 3 months of

drought (usually March to May) and 4 months of frequently heavy rains

(June to September).

Rain, heavy dews or fog during the blooming

season (November to March in Florida) are deleterious, stimulating tree

growth but interfering with flower production and encouraging fungus

diseases of the inflorescence and fruit. In Queensland, dry areas with

rainfall of 40 in (100 cm), 75% of which occurs from January to March,

are favored for mango growing because vegetative growth is inhibited

and the fruits are well exposed to the sun from August to December,

become well colored, and are relatively free of disease. Strong winds

during the fruiting season cause many fruits to fall prematurely.

Soil

The

mango tree is not too particular as to soil type, providing it has good

drainage. Rich, deep loam certainly contributes to maximum growth, but

if the soil is too rich and moist and too well fertilized, the tree

will respond vegetatively but will be deficient in flowering and

fruiting. The mango performs very well in sand, gravel, and even

oolitic limestone (as in southern Florida and the Bahamas).

A

polyembryonic seedling, 'No. 13-1', introduced into Israel from Egypt

in 1931, has been tested since the early 1960's in various regions of

the country for tolerance of calcareous soils and saline conditions. It

has done so well in sand with a medium (15%) lime content and highly

saline irrigation water (over 600 ppm) that it has been adopted as the

standard rootstock in commercial plantings in salty, limestone

districts of Israel. Where the lime content is above 30%, iron chelates

are added.

Propagation

Mango

trees grow readily from seed. Germination rate and vigor of seedlings

are highest when seeds are taken from fruits that are fully ripe, not

still firm. Also, the seed should be fresh, not dried. If the seed

cannot be planted within a few days after its removal from the fruit,

it can be covered with moist earth, sand, or sawdust in a container

until it can be planted, or kept in charcoal dust in a dessicator with

50% relative humidity. Seeds stored in the latter manner have shown 80%

viability even after 70 days. High rates of germination are obtained if

seeds are stored in polyethylene bags but the seedling behavior may be

poor. Inclusion of sphagnum moss in the sack has no benefit and shows

inferior rates of germination over 2- to 4-week periods, and none at

all at 6 weeks.

The flesh should be completely removed. Then the

husk is opened by carefully paring around the convex edge with a sharp

knife and taking care not to cut the kernel, which will readily slide

out. Husk removal speeds germination and avoids cramping of roots, and

also permits discovery and removal of the larva of the seed weevil in

areas where this pest is prevalent. Finally, the husked kernels are

treated with fungicide and planted without delay. The beds must have

solid bottoms to prevent excessive taproot growth, otherwise the

taproot will become 18 to 24 in (45-60 cm) long while the top will be

only one third to a half as high, and the seedling will be difficult to

transplant with any assurance of survival. The seed is placed on its

ventral (concave) edge with 1/4 protruding above the sand. Sprouting

occurs in 8 to 14 days in a warm, tropical climate; 3 weeks in cooler

climates. Seedlings generally take 6 years to fruit and 15 years to

attain optimum yield for evaluation.

However, the fruits of

seedlings may not resemble those of the parent tree. Most Indian mangos

are monoembryonic; that is, the embryo usually produces a single

sprout, a natural hybrid from accidental crossing, and the resulting

fruit may be inferior, superior, or equal to that of the tree from

which the seed came. Mangos of Southeast Asia are mostly polyembryonic.

In these, generally, one of the embryos in the seed is a hybrid; the

others (up to 4) are vegetative growths which faithfully reproduce the

characteristics of the parent. The distinction is not absolute, and

occasionally a seed supposedly of one class may behave like the other.

Seeds

of polyembryonic mangos are most convenient for local and international

distribution of desirable varieties. However, in order to reproduce and

share the superior monoembryonic selections, vegetative propagation is

necessary. Inarching and approach-grafting are traditional in India.

Tongue-, saddle-, and root-grafting (stooling) are also common Indian

practices. Shield- and patch-grafting have given up to 70% success but

the Forkert system of budding has been found even more practical. After

many systems were tried, veneer grafting was adopted in Florida in the

mid-1950's.

Choice of rootstock is important. Use of seedlings

of unknown parentage has resulted in great variability in a single

cultivar. Some have believed that polyembryonic rootstocks are better

than monoembryonic, but this is not necessarily so. In trials at Tamil

Nadu Agricultural University, 10-year-old trees of 'Neelum' grafted on

polyembryonic 'Bapakkai' showed vigor and spread of tree and

productivity far superior to those grafted on 'Olour' which is also

polyembryonic. Those grafted on monoembryonic rootstock also showed

better growth and yield than those on 'Olour'. In 1981, experimenters

at Lucknow, India, reported the economic advantage of "stone-grafting",

which requires less space in the nursery and results in greater

uniformity. Scions from the spring flush of selected cultivars are

defoliated and, after a 10-day delay, are cleft-grafted on 5-day-old

seedlings which must thereafter be kept in the shade and protected from

drastic changes in the weather.

Old trees of inferior types are

top-worked to better cultivars by either side-grafting or

crown-grafting the beheaded trunk or beheaded main branches. Such trees

need protection from sunburn until the graft affords shade. In South

Africa, the trunks are whitewashed and bunches of dry grass are tied

onto cut branch ends. The trees will bear in 2 to 3 years. Attempts to

grow 3 or 4 varieties on one rootstock may appear to succeed for a

while but the strongest always outgrows the others.

Cuttings, even

when treated with growth regulators, are only 40% successful. Best

results are obtained with cuttings of mature trees, ringed 40 days

before detachment, treated, and rooted under mist. But neither cuttings

nor air layers develop good root systems and are not practical for

establishing plantations. Clonal propagation through tissue culture is

in the experimental stage.

In spite of vegetative propagation,

mutations arise in the form of bud sports. The fruit may differ

radically from the others on a grafted tree-perhaps larger and

superior-and the foliage on the branch may be quite unlike that on

other branches.

Dwarfing

Reduction

in the size of mango trees would be a most desirable goal for the

commercial and private planter. It would greatly assist harvesting and

also would make it possible for the homeowner to maintain trees of

different fruiting seasons in limited space.

In India,

double-grafting has been found to dwarf mango trees and induce early

fruiting. Naturally dwarf hybrids such as 'Julie' have been developed.

The polyembryonic Indian cultivars, 'Olour' and 'Vellai Colamban', when

used as rootstocks, have a dwarfing effect; so has the polyembryonic

'Sabre' in experiments in Israel and South Africa.

In Peru, the

polyembryonic 'Manzo de Ica', is used as rootstock; in Colombia,

'Hilaza' and 'Puerco'. 'Kaew' is utilized in Thailand.

Culture

About

6 weeks before transplanting either a seedling or a grafted tree, the

taproot should be cut back to about 12 in (30 cm). This encourages

feeder-root development in the field. For a week before setting out,

the plants should be exposed to full morning sun.

Inasmuch as

mango trees vary in lateral dimensions, spacing depends on the habit of

the cultivar and the type of soil, and may vary from 34 to 60 ft

(10.5-18 m) between trees. Closer planting will ultimately reduce the

crop. A spacing of 34 x 34 ft (10.5 x l0.5 m) allows 35 trees per acre

(86 per ha); 50 x 50 ft (15.2 x l5.2 m) allows only 18 trees per acre

(44.5 per ha). In Florida's limestone, one commercial grower maintains

100 trees per acre (247 per ha), controlling size by hedging and

topping.

The young trees should be placed in prepared and

enriched holes at least 2 ft (60 cm) deep and wide, and 3/4 of the top

should be cut off. In commercial groves in southern Florida, the trees

are set at the intersection of cross trenches mechanically cut through

the limestone.

Mangos require high nitrogen fertilization in the

early years but after they begin to bear, the fertilizer should be

higher in phosphate and potash. A 5-8-10 fertilizer mix is recommended

and applied 2 or 3, or possibly even 4, times a year at the rate of 1

lb (454 g) per year of age at each dressing. Fertilizer formulas will

vary with the type of soil. In sandy acid soils, excess nitrogen

contributes to "soft nose" breakdown of the fruits. This can be

counteracted by adding calcium. On organic soils (muck and peat),

nitrogen may be omitted entirely. In India, fertilizer is applied at an

increasing rate until the tree is rather old, and then it is

discontinued. Ground fertilizers are supplemented by foliar nutrients

including zinc, manganese and copper. Iron deficiency is corrected by

small applications of chelated iron.

Indian growers generally

irrigate the trees only the first 3 or 4 years while the taproot is

developing and before it has reached the water table. However, in

commercial plantations, irrigation of bearing trees is withheld only

for the 2 or 3 months prior to flowering. When the blooms appear, the

tree is given a heavy watering and this is repeated monthly until the

rains begin. In Florida groves, irrigation is by means of overhead

sprinklers which also provide frost protection when needed.

Usually

no pruning is done until the 4th year, and then only to improve the

form and this is done right after the fruiting season. If topping is

practiced, the trees are cut at 14 ft (4.25 m) to facilitate both

spraying and harvesting. Grafted mangos may set fruit within a year or

two from planting. The trees are then too weak to bear a full crop and

the fruits should be thinned or completely removed.

Harvesting

Mangos

normally reach maturity in 4 to 5 months from flowering. Fruits of

"smudged" trees ripen several months before those of untreated trees.

Experts in the Philippines have demonstrated that 'Carabao' mangos

sprayed with ethephon (200 ppm) 54 days after full bloom can be

harvested 2 weeks later at recommended minimum maturity. The fruits

will be larger and heavier even though harvested 2 weeks before

untreated fruits. If sprayed at 68 days after full bloom and harvested

2 weeks after spraying, there will be an improvement in quality in

regard to soluble solids and titratable acidity.

When the mango

is full-grown and ready for picking, the stem will snap easily with a

slight pull. If a strong pull is necessary, the fruit is still somewhat

immature and should not be harvested. In the more or less red types of

mangos, an additional indication of maturity is the development of a

purplish-red blush at the base of the fruit. A long-poled picking bag

which holds no more than 4 fruits is commonly used by pickers. Falling

causes bruising and later spoiling. When low fruits are harvested with

clippers, it is desirable to leave a 4-inch (10 cm) stem to avoid the

spurt of milky/resinous sap that exudes if the stem is initially cut

close. Before packing, the stem is cut off 1/4 in (6 mm) from the base

of the fruit. In Queensland, after final clipping of the stem, the

fruits are placed stem-end-down to drain.

In a sophisticated

Florida operation, harvested fruits are put into tubs of water on

trucks in order to wash off the sap that exudes from the stem end. At

the packing house, the fruits are transferred from the tubs to bins,

graded and sized and packed in cartons ("lugs") of 8 to 20 each

depending on size. The cartons are made mechanically at the packing

house and hold 14 lbs (6.35 kg) of fruit. The filled cartons are

stacked on pallets and fork-lifted into refrigerated trucks with

temperature set at no less than 55º F (12.78º C) for transport

to distribution centers in major cities throughout the USA and Canada.

Yield

The

yield varies with the cultivar and the age of the tree. At 10 to 20

years, a good annual crop may be 200 to 300 fruits per tree. At twice

that age and over, the crop will be doubled. In Java, old trees have

been known to bear 1,000 to 1,500 fruits in a season. Some cultivars in

India bear 800 to 3,000 fruits in "on" years and, with good cultural

attention, yields of 5,000 fruits have been reported. There is a famous

mango, 'Pane Ka Aam' of Maharashtra and Khamgaon, India, with

"paper-thin" skin and fiberless flesh. One of the oldest of these

trees, well over 100 years of age, bears heavily 5 years out of 10 with

2 years of low yield. Average annual yield is 6,500 fruits; the highest

record is 29,000.

Reported annual yields for 6 cultivars in Puerto Rico are:

| 'Lippens' |

67,079 lbs per acre |

| 'Keitt' |

45,608

lbs per acre |

| 'Earlygold' |

42,310

lbs per acre |

| 'Parvin' |

38,369

lbs per acre |

| 'Haden' |

32,732

lbs per acre |

| 'Palmer' |

28,868

lbs per acre |

The number of lbs per acre is roughly the equivalent of kg per hectare.

Average

mango yield in Florida is said to be about 30,000 lbs/acre. One leading

commercial grower has reported his annual crop as 22,000 to 27,500

lbs/acre. One grower who has hedged and topped trees close-planted at

the rate of 100 per acre (41/ha) averages 14,000 to 19.000 lbs/acre.

Ripening

In

India, mangos are picked quite green to avoid bird damage and the

dealers layer them with rice straw in ventilated storage rooms over a

period of one week. Quality is improved by controlled temperatures

between 60º and 70º F (15º -21º C). In ripening trials

in Puerto Rico, the 'Edward' mango was harvested while deep-green,

dipped in hot water at 124º F (51º C) to control anthracnose,

sorted as to size, then stored for 15 days at 70º F (21º C)

with relative humidity of 85% to 90%. Those picked when more than 3 in

(7.5 cm) in diameter ripened satisfactorily and were of excellent

quality.

Ethylene treatment causes green mangos to develop full

color in 7 to 10 days depending on the degree of maturity, whereas

untreated fruits require 10 to 15 days. One of the advantages is that

there can be fewer pickings and the fruit color after treatment is more

uniform. Therefore, ethylene treatment is a common practice in Israel

for ripening fruits for the local market. Some growers in Florida

depend on ethylene treatment. Generally, 24 hours of exposure is

sufficient if the fruits are picked at the proper stage. It has been

determined that mangos have been picked prematurely if they require

more than 48 hours of ethylene treatment and are not fit for market.

Keeping

Quality and Storage

Washing

the fruits immediately after harvest is essential, as the sap which

leaks from the stem bums the skin of the fruit making black lesions

which lead to rotting.

Some cultivars, especially 'Bangalora',

'Alphonso', and 'Neelum' in India, have much better keeping quality

than others. In Bombay, 'Alphonso' has kept well for 4 weeks at 52º

F (11.11º C); 6 to 7 weeks at 45º F (7.22º C). Storage at

lower temperatures is detrimental inasmuch as mangos are very

susceptible to chilling injury. Any temperature below 55.4º F

(13º C) is damaging to 'Kent'. In Florida, this is regarded as the

optimum for 2 to 3 weeks storage. The best ripening temperatures are

70º to 75º F (21.11º-23.89º C).

Experiments in

Florida have demonstrated that 'Irwin', 'Tommy Atkins' and 'Kent'

mangos, held for 3 weeks at storage temperature of 55.4º F (13º

C), 98% to 100% relative humidity and atmospheric pressure of 76 or 152

mmHg, ripened thereafter with less decay at 69.8º F (21º C)

under normal atmospheric pressure, as compared with fruits stored at

the same temperature with normal atmospheric pressure. Those stored at

152 mmHg took 3 to 5 days longer to ripen than those stored at 76 mmHg.

Decay rates were 20% for 'Tommy Atkins' and 40% for 'Irwin'. Spoilage

from anthracnose has been reduced by immersion for 15 min in water at

125º F (51.67º C) or for 5 min at 132º F (55.56º C).

Dipping in 500 ppm maleic hydrazide for 1 min and storing at 89.6º

F (32º C) also retards decay but not loss of moisture. In South

Africa, mangos are submerged immediately after picking in a suspension

of benomyl for 5 min at 131º F (55º C) to control soft brown

rot.

In Australia, mature-green 'Kensington Pride' mangos have

been dipped in a 4% solution of calcium chloride under reduced pressure

(250 mm Hg) and then stored in containers at 77º F (25º C) in

ethylene-free atmosphere. Ripening was retarded by a week; that is, the

treated fruits ripened in 20 to 22 days whereas controls ripened in 12

to 14 days. Eating quality was equal except that the calcium-treated

fruits were found slightly higher in ascorbic acid.

Wrapping

fruits individually in heat-shrinkable plastic film has not retarded

decay in storage. The only benefit has been 3% less weight loss.

Coating with paraffin wax or fungicidal wax and storing at 68º to

89.6º F (20º -32º C) delays ripening 1 to 2 weeks and

prevents shriveling but interferes with full development of color.

Gamma

irradiation (30 Krad) causes ripening delay of 7 days in mangos stored

at room temperature. The irradiated fruits ripen normally and show no

adverse effect on quality. Irradiation has not yet been approved for

this purpose.

In India, large quantities of mangos are

transported to distant markets by rail. To avoid excessive heat buildup

and consequent spoilage, the fruits, padded with paper shavings, are

packed in ventilated wooden crates and loaded into ventilated wooden

boxcars. Relative humidity varies from 24% to 85% and temperature from

88º to 115º F (31.6º-46.6º C). These improved

conditions have proved superior to the conventional packing of the

fruits in Phoenix-palm-midrib or bamboo, or the newer pigeonpea-stem,

baskets padded with rice straw and mango leaves and transported in

steel boxcars, which has resulted in 20% to 30% losses from shriveling,

unshapeliness and spoilage.

Green seedling mangos, harvested in

India for commercial preparation of chutneys and pickles as well as for

table use, are stored for as long as 40 days at 42º to 45º F

(5.56º-7.22º C) with relative humidity of 85% to 99%. Some of

these may be diverted for table use after a 2-week ripening period at

62º to 65º F (16.67º -18.13º C).

Pests and

Diseases

The fruit flies, Dacus

ferrugineus and D.

zonatus, attack the mango in India; D. tryoni (now Strumeta tryoni) in

Queensland, and D.

dorsalis in the Philippines; Pardalaspis cosyra

in Kenya; and the fruit fly is the greatest enemy of the mango in

Central America. Because of the presence of the Caribbean fruit fly, Anastrepha suspensa,

in Florida, all Florida mangos for interstate shipment or for export

must be fumigated or immersed in hot water at 115º F (46.11º C)

for 65 minutes.

In India, South Africa and Hawaii, mango seed weevils, Sternochetus (Cryptorhynchus) mangiferae and S. gravis,

are major pests, undetectable until the larvae tunnel their way out.

The leading predators of the tree in India are jassid hoppers (Idiocerus

spp.) variously attacking trunk and branches or foliage and flowers,

and causing shedding of young fruits. The honeydew they excrete on

leaves and flowers gives rise to sooty mold.

The mango-leaf webber, or "tent caterpillar", Orthaga euadrusalis,

has become a major problem in North India, especially in old, crowded

orchards where there is excessive shade. Around Lucknow, 'Dashehari' is

heavily infested by this pest; 'Samarbehist' ('Chausa') less. In South

Africa, 11 species of scales have been recorded on the fruits. Coccus mangiferae

and C. acuminatus

are the most common scale insects giving rise to the sooty mold that

grows on the honeydew excreted by the pests.

In some areas, there are occasional outbreaks of the scales, Pulvinaria psidii, P. polygonata, Aulacaspis

cinnamoni, A. tubercularis,

Aspidiotus destructor and Leucaspis indica.

In Florida, pyriform scale, Protopulvinaria

pyrformis, and Florida wax scale, Ceroplastes floridensis,

are common, and the lesser snow scale, Pinnaspis strachani,

infests the trunks of small trees and lower branches of large trees.

Heavy attacks may result in cracking of the bark and oozing of sap.

The citrus thrips, Scirtothrips

aurantii, blemishes the fruit in some mango-growing areas.

The red-banded thrips, Selenothrips

rubrocinctus, at times heavily infests mango foliage in

Florida, killing young leaves and causing shedding of mature leaves.

Mealybugs, Phenacoccus

citri and P.

mangiferae, and Drosicha

stebbingi and D.

mangiferae may infest young leaves, shoots and fruits. The

mango stem borer, Batocera

rufomaculata invades the trunk. Leaves and shoots are

preyed on by the caterpillars of Parasa

lepida, Chlumetia

transversa and Orthaga

exvinacea. Mites feed on mango leaves, flowers and young

fruits. In Florida, the most common is the avocado red mite, Paratetranychus yothersii.

Mistletoe (Loranthus

and Viscum

spp.) parasitizes and kills mango branches in India and tropical

America. Dr. B. Reddy, Regional Plant Production and Protection

Officer, FAO, Bangkok, compiled an extensive roster of insects, mites,

nematodes, other pests, fungi, bacteria and phanerogamic parasites in

Southeast Asia and the Pacific Region (1975).

One of the most serious diseases of the mango is powdery mildew (Oidium mangiferae),

which is common in most growing areas of India, occurs mostly in March

and April in Florida. The fungus affects the flowers and causes young

fruits to dehydrate and fall, and 20% of the crop may be lost. It is

controllable by regular spraying. In humid climates, anthracnose caused

by Colletotrichum

gloeosporioides (Glomerella

cingulata)

affects flowers, leaves, twigs, fruits, both young and mature. The

latter show black spots externally and the corresponding flesh area is

affected.

Control measures must be taken in advance of flowering

and regularly during dry spells. In Florida, mango growers apply up to

20 sprayings up to the cut-off point before harvesting. The black spots

are similar to those produced by Alternaria

sp. often associated with anthracnose in cold storage in India. Inside

the fruits attacked by Alternaria

there are corresponding areas of hard, corky, spongy lesions. Inasmuch

as the fungus enters the stem-end of the fruit, it is combatted by

applying Fungicopper paste in linseed oil to the cut stem and also by

sterilizing the storage compartment with Formalin 1:20. A pre-harvest

dry stem-end rot was first noticed on 'Tommy Atkins' in Mexico in 1973,

and it has spread to all Mexican plantings of this cultivar causing

losses of 10-80% especially in wet weather. Fusarium, Alternaria and Cladosporium spp.

were prominent among associated fungi.

Malformation of inflorescence and vegetative buds is attributed to the

combined action of Fusarium

moniliforme and any of the mites, Aceria mangifera, Eriophyes

sp., Tyrophagus

castellanii, or Typhlodromus

asiaticus.

This grave problem occurs in Pakistan, India, South Africa and Egypt,

El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico, Brazil and Venezuela, but not as yet in

the Philippines. It is on the increase in India. Removing and burning

the inflorescence has been the only remedy, but it has been found that

malformation can be reduced by a single spray of NAA (200 mg in 50 ml

alcohol with water added to make 1 liter) in October, and deblooming in

early January.

There are 14 types of mango galls in India, 12 occurring on the leaves.

The most serious is the axillary bud gall caused by Apsylla cistellata

of the family Psyllidae.

In Florida, leaf spot is caused by Pestalotia

mangiferae, Phyllosticta

mortoni, and Septoria

sp.; algal leaf spot, or green scurf by Cephaleuros virescens.

In 1983, a new disease, crusty leaf spot, caused by the fungus, Zimmermaniella trispora,

was reported as common on neglected mango trees in Malaya. Twig dieback

and dieback are from infection by Phomopsis

sp., Physalospora abdita,

and P. rhodina.

Wilt is caused by Verticillium

alboatrum; brown felt by Septobasidium pilosum

and S.

pseudopedicellatum; wood rot, by Polyporus sanguineus;

and scab by Elsinoe

mangiferae (Sphaceloma

mangiferae). Cercospora

mangiferae attacks the fruits in the Congo.

A

number of organisms in India cause white sap, heart rot, gray blight,

leaf blight, white pocket rot, white spongy rot, sap rot, black bark

and red rust. In South Africa, Asbergillus

attacks young shoots and fruit rot is caused by A. niger. Gloeosporium mangiferae

causes black spotting of fruits. Erwinia

mangiferae and Pseudomonas

mangiferaeindicae are sources of bacterial black spot in

South Africa and Queensland. Bacterium

carotovorus is a source of soft rot. Stem-end rot is a

major problem in India and Puerto Rico from infection by Physalospora rhodina

(Diplodia natalensis).

Soft brown rot develops during prolonged cold storage in South Africa.

Leaf

tip burn may be a sign of excess chlorides. Manganese deficiency is

indicated by paleness and limpness of foliage followed by yellowing,

with distinct green veins and midrib, fine brown spots and browning of

leaf tips. Inadequate zinc is evident in less noticeable paleness of

foliage, distortion of new shoots, small leaves, necrosis, and stunting

of the tree and its roots. In boron deficiency, there is reduced size

and distortion of new leaves and browning of the midrib. Copper

deficiency is seen in paleness of foliage and severe tip-bum with

gray-brown patches on old leaves; abnormally large leaves; also

die-back of terminal shoots; sometimes gummosis of twigs and branches.

Magnesium is needed when young trees are stunted and pale, new leaves

have yellow-white areas between the main veins and prominent yellow

specks on both sides of the midrib. There may also be browning of the

leaf tips and margins. Lack of iron produces chlorosis in young trees.

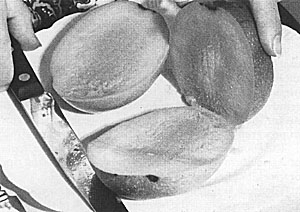

Fig.

61: Low-fiber mangoes are easily prepared for the table by first

cutting off the "cheeks" which can then be served for eating by

spooning the flesh from the "shell".

Food Uses

Mangos

should always be washed to remove any sap residue, before handling.

Some seedling mangos are so fibrous that they cannot be sliced;

instead, they are massaged, the stem-end is cut off, and the juice

squeezed from the fruit into the mouth. Non-fibrous mangos may be cut

in half to the stone, the two halves twisted in opposite directions to

free the stone which is then removed, and the halves served for eating

as appetizers or dessert. Or the two "cheeks" may be cut off, following

the contour of the stone, for similar use; then the remaining side

"fingers" of flesh are cut off for use in fruit cups, etc.

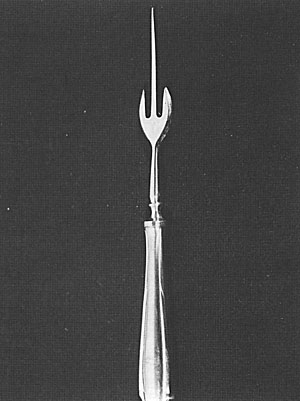

Most

people enjoy eating the residual flesh from the seed and this is done

most neatly by piercing the stem-end of the seed with the long central

tine of a mango fork, commonly sold in Mexico, and holding the seed

upright like a lollypop. Small mangos can be peeled and mounted on the

fork and eaten in the same manner. If the fruit is slightly fibrous

especially near the stone, it is best to peel and slice the flesh and

serve it as dessert, in fruit salad, on dry cereal, or in gelatin or

custards, or on ice cream. The ripe flesh may be spiced and preserved

in jars. Surplus ripe mangos are peeled, sliced and canned in sirup, or

made into jam, marmalade, jelly or nectar. The extracted pulpy juice of

fibrous types is used for making mango halva and mango leather.

Sometimes corn flour and tamarind seed jellose are mixed in. Mango

juice may be spray-dried and powdered and used in infant and invalid

foods, or reconstituted and drunk as a beverage. The dried juice,

blended with wheat flour has been made into "cereal" flakes, A

dehydrated mango custard powder has also been developed in India,

especially for use in baby foods.

Ripe mangos may be frozen

whole or peeled, sliced and packed in sugar (1 part sugar to 10 parts

mango by weight) and quick-frozen in moisture-proof containers. The

diced flesh of ripe mangos, bathed in sweetened or unsweetened lime

juice, to prevent discoloration, can be quick-frozen, as can sweetened

ripe or green mango puree. Immature mangos are often blown down by

spring winds. Half-ripe or green mangos are peeled and sliced as

filling for pie, used for jelly, or made into sauce which, with added

milk and egg whites, can be converted into mango sherbet. Green mangos

are peeled, sliced, parboiled, then combined with sugar, salt, various

spices and cooked, sometimes with raisins or other fruits, to make

chutney; or they may be salted, sun-dried and kept for use in chutney

and pickles. Thin slices, seasoned with turmeric, are dried, and

sometimes powdered, and used to impart an acid flavor to chutneys,

vegetables and soup. Green or ripe mangos may be used to make relish.

In Thailand, green-skinned mangos

of a class called "keo", with sweet, nearly fiberless flesh and very

commonly grown and inexpensive on the market, are soaked whole for 15

days in salted water before peeling, slicing and serving with sugar.

Processing

of mangos for export is of great importance in Hawaii in view of the

restrictions on exporting the fresh fruits. Hawaiian technologists have

developed methods for steam- and lye-peeling, also devices for removing

peel from unpeeled fruits in the preparation of nectar. Choice of

suitable cultivars is an essential factor in processing mangos for

different purposes.

The Food Research Institute of the Canada

Department of Agriculture has developed methods of preserving ripe or

green mango slices by osmotic dehydration.

The fresh kernel of

the mango seed (stone) constitutes 13% of the weight of the fruit, 55%

to 65% of the weight of the stone. The kernel is a major by-product of