The Sapote

Calocarpum Mammosum, Pierre

The sapote is one of the important fruits of the Central American

lowlands. It furnishes to the Indians a nourishing and agreeable food,

obtainable during a certain part of the year in considerable abundance.

Cook and Collins remark : "It was this fruit that kept Cortes and his

army alive on their famous march from Mexico City to Honduras."

In

the hot and humid lowlands the sapote becomes a large tree, often 65

feet high, with a thick trunk and stout branches. The Indians, when

clearing the forest in order to plant coffee or other crops, usually

spare the sapote trees they encounter, for they regard the fruit

highly. The foliage is abundant, and light green in color. The leaves,

which are clustered toward the ends of the stout branchlets, are

obovate to oblanceolate in outline, broadest toward the apex, and 4 to

10 inches long. The small flowers are produced in great numbers along

the branchlets. The sepals are eight to ten, imbricate, in several

series; the corolla is tubular, whitish, with five lobes. The stamens

are five and the ovary is hairy, five-celled, with one ovule in each

cell. The fruit is elliptic or oval in form, commonly 3 to 6 inches

long, russet-brown in color, the skin thick and woody and the surface

somewhat scurfy. The flesh is firm, salmon-red to reddish brown in

color, and finely granular in texture. The large elliptic seed can be

lifted out of the fruit as easily as that of an avocado; it is hard,

brown, and shining, except on the ventral surface, which is whitish and

somewhat rough. To one unaccustomed to the exceedingly sweet fruits of

the tropics, the flavor of the sapote is at first somewhat cloying

because of its richness and lack of acidity. When made into a sherbet,

as is done in Habana, it is sure to be relished at first trial.

Inferior or improperly ripened sapotes will be found to have a

pronounced squash-like flavor.

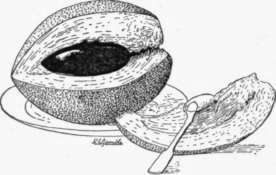

Fig. 44. The sapote (Calocarpum

mammosum). (X 1/3)

Pittier,

whose studies of the sapotaceous fruits have done much to clear away

the botanical confusion in which they have been involved, considers the

sapote to be indigenous to Central America. Outside of its native area

it is grown in the West Indies, in South America, and in the

Philippines. In Cuba it is particularly abundant and the fruit highly

esteemed. Though it has been planted in southeastern Florida it has

never succeeded in that region. The limiting factor there seems to be

unfavorable soil rather than temperature, while in California it has

always succumbed to the cold, even when grown in the most protected

situations.

In the British West Indies the sapote is called

mammee-sapota, marmalade-plum, and marmalade-fruit. In the French West

Indies it is known as sapote and grosse sapote. In Cuba it is called

mamey Colorado and, less commonly, mamey zapote. Throughout its native

area, southern Mexico and Central America, it is known in Spanish as

zapote (from the Nahuatl or Aztec name tzapotl) and this name is used

also in Ecuador and Colombia. In the Philippines the term is

chico-mamey. The more important botanical synonyms are : Achras mammosa, L.,

Lucuma

mammosa, Gaertn., Vitellaria

mammosa, Radlk., and Achradelpha

mammosa, Cook. The name mamey, improperly applied to this

fruit, results in its being confused with Mammea americana, L.

The

Indians of Central America commonly eat the sapote out of hand, but it

is occasionally made into a rich preserve and it may be employed in

other ways. In Cuba it is used as a "filler" in making guava-cheese,

and a thick jam, called crema de mamey Colorado, is also prepared from

it. The seed is an article of commerce in Central America, where the

large kernel is roasted and used to mix with cacao in making chocolate.

The

tree is tropical in its requirements. In Guatemala it is most abundant

at elevations from sea-level to 2000 feet; at 3000 feet it is still

quite common, but at 4000 feet it is rarely seen. At higher elevations

it is injured by the cold and makes very slow growth. It thrives on

heavy soils, such as the clays and clay-loams of Guatemala. It is

believed in Florida that the plant does not like a soil which is rich

in lime, and that for this reason it has failed to succeed at Miami and

other points in the state where conditions otherwise seem to be

favorable. P. W. Reasoner considered it to be as frost-resistant as the

sapodilla.

Seedlings start bearing when seven or eight years old

if grown under favorable conditions, and when of good size yield

regularly and abundantly. The fruits are picked when mature, and laid

away in a cool place to ripen, which requires about a week. If shipped

as soon as picked from the tree, they can be sent to northern markets

without difficulty. Sapotes from Cuba and Central America are often

seen in the markets of Tampa and New Orleans. The season of ripening

extends over a period of two or three months, usually beginning about

August in the West Indies and Central America. Differences in

elevation, and consequently in climate of course affect the time of

ripening.

All of the sapote trees in tropical America are

seedlings. Neither budding nor grafting has yet been used with this

species, so far as is known. The seeds, which cannot be kept long,

germinate more readily if the thick husk is removed before planting.

They should be placed in sand or light soil, laid on their sides, and

scarcely covered. When the young plants are six or eight inches high,

they may be transferred to four- or five-inch pots. Their growth is

rapid at first, but much slower after they have exhausted the food

reserves stored in the large seed. It is probable that budding will

prove as successful with the sapote as it has with the sapodilla.

Seedlings differ greatly in the size, shape, and quality of their

fruits. The best one should be propagated by some vegetative means.

Back to

Mamey

Sapote Page

|