From the Manual Of

Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Litchi and

its Relatives

Litchi chinensis, Sonn.

While living in exile at Canton, the poet Su Tung-po declared that

litchis would reconcile one to eternal banishment. Yet he did not allow

his enthusiasm to draw him into gastronomic indiscretions, for he

limited himself to a modest three hundred a day, while other men (so he

says) did not stop short of a thousand.

Chang Chow-ling, an illustrious statesman of the eighth century of our

era, composed a poem on the litchi in which he praised it as the most

luscious of all fruits. Modern Chinese critics fully concur in this

opinion. Neither the orange nor the peach, two of the finest fruits of

southern China, is held to equal it in quality.

Nor is the litchi one of those rare and delicate fruits known only to

the favored few. In southern Asia, where its cultivation dates back at

least two thousand years, it is grown extensively and millions are

familiar with it. That it should still be unknown in most parts of the

western tropics is probably due to the perishable nature of the seeds.

Before the days of steam navigation, it was difficult to transport them

successfully from one continent to another.

"An orchard of litchis," wrote the eminent E. Bonavia of India, "say of

a few hundred trees, and with ordinary care, would give a handsome and

almost certain annual return for not improbably a hundred years." While

it has been considered that the litchi is somewhat exacting in its

cultural requirements, it can be grown successfully in many parts of

the tropics and subtropics. Now that it has been established in

tropical America, there is no reason why it should not there become one

of the common fruits, nor why fresh litchis should not be found on

fruit-stands of northern cities at least as abundantly as are the dried

ones at present.

It is in the form of dried litchis, "litchi nuts," that North Americans

are usually acquainted with this fruit. The Chinese who live in the

United States import them in large quantities, and are particularly

prone to indulging in them at the time of their New Year celebrations.

But the dried litchi resembles the fresh one even less than the dried

apple of the grocery store resembles a Gravenstein just picked from the

tree. To appreciate its excellence, one must taste the fresh litchi;

although a fairly true estimate of it may be acquired from the canned

or preserved product, which much resembles preserved Muscat grapes in

flavor.

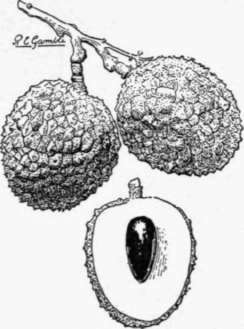

Fig. 42.

Fruits of a good variety of the litchi. Kinds which are altogether

seedless have been reported, but in the best-known sorts the seed is

about the size of the one here shown. (X J)

Judging by the experience of the past few years, it should be possible

to produce litchis commercially in southwestern Florida (the Fort Myers

region), where there is relative freedom from frost and where the soils

are deep and moist. It is doubtful whether there are any localities in

southern California adapted to commercial litchi culture, but trees

have been grown at Santa Barbara and in the foothill region near Los

Angeles (Monrovia, Glendora). While the dry climate and cool winter

weather of California are unfavorable, it seems probable that litchis

may be grown on a small scale in this state, if planted in sheltered

situations and given protection from frost for the first few years.

Because of its value as an ornamental tree, the litchi is recommended

for planting in parks and gardens. It grows to an ultimate height of 35

or 40 feet (less in some regions), and forms a broad round-topped crown

well supplied with glossy light green foliage. The leaves are compound,

with two to four pairs of elliptic-oblong to lanceolate, sharply acute,

glabrous leaflets 2 to 3 inches long. The flowers, which are small and

unattractive, are borne in terminal panicles sometimes a foot in

length. They are said to appear in northern India in February and in

China during April. The fruits, which are produced in loose clusters of

two or three to twenty or even more, have been likened to strawberries

in appearance. In shape they are oval to ovate, in diameter 1 1/2

inches in the better varieties, and in color deep rose when fully ripe,

changing to dull brown as the fruit dries. The outer covering is hard

and brittle, rough on the surface and divided into small scale-like

areas. The seed is small, shriveled, and ot viable in some of the

grafted varieties; in seedlings it is as large as a good-sized

castor-bean, and glossy dark brown in color. Surrounding it and

separating from it readily is the flesh (technically aril), which is

white, translucent, firm, and juicy. The flavor is subacid, suggestive

of the Bigar-reau cherry or (according to some) the Muscat grape.

Regarding the origin and early history of the fruit Alphonse DeCandolle

says: "Chinese authors living at Pekin only knew the litchi late in the

third century of our era. Its introduction into Bengal took place at

the end of the eighteenth century. Every one admits that the species is

a native of the south of China, and, Blume adds, of Cochin-China and

the Philippine Islands, but it does not seem that any botanist has

found it in a truly wild state. This is probably because the southern

part of China towards Siam has been little visited. In Cochin-China and

in Burma and at Chittagong the litchi is only cultivated."

Macgowan 1 recounts that litchis were first sent

as tribute to the emperor Kao Tsu about 200 B.C. These were dried

fruits, however; later fresh ones were forwarded by relays of men, and

one is happy to learn that though the cost in human life was frightful

they reached the emperor in good condition. The Emperor Wu Ti (140-87

B.C.) made several attempts to bring trees from Annam and plant them in

his garden at Chang-an, but he was not successful in raising them.

According to Walter T. Swingle, the first published work devoted

exclusively to fruit-culture was written by a Chinese scholar in 1056

a.d. on the varieties of the litchi.

The principal provinces of China in which litchis are grown are Fukien,

Kwantung, and Szechwan. In Kwangtung Province alone the annual crop is

said to be twenty million to thirty million pounds, worth $1,000,000 to

$1,500,000. The region around Canton is considered the most favorable

part of China for litchi culture. North of Foochow the tree is not

successful.

While litchis are by no means so extensively grown in India as they are

in southern China, there are several districts in which they are

produced commercially. The most important are said to be in Bengal;

about Muzaffarpur (in Bihar); and at Saharanpur (United Provinces of

Agra and Oudh). E.

1 Journal of the Agri-Horticultural

Society of India, 1884, p. 195.

Bonavia says: "The tree does admirably in Lucknow, and should do as

well all over the northwestern provinces, but it flourishes best, I

believe, in Bengal. Who knows what untold litchi wealth there may be in

the fine black soil of the central provinces, so centrally situated for

fruit trade?"

In Cochin-China, in Madagascar, and in a few other countries of the

East, the tree is cultivated on a limited scale. In Hawaii, where it is

believed to have been introduced about 1873, it has succeeded

remarkably well, and much attention has lately been given to its

commercial cultivation, without, however, any large orchards having

been established as yet.

According to William Harris, it was introduced into Jamaica in 1775,

but it is still rare in that island. A tree at Santa Barbara,

California, which produced a few fruits in 1914, was the first to come

into bearing in the United States. While the litchi is believed to have

been planted in Florida as early as 1886, it was not until 1916 that

the first fruits were produced in that state. These were from plants

introduced from China in 1906. A few trees have borne in Cuba, Brazil,

and other parts of tropical America.

The common name of this fruit is variously spelled, - litchi, lichee,

lychee, leechee, lichi, laichi, and so on. Yule and Burnell state that

the pronunciation in northern China is lee-chee, while in the southern

part of the country it is ly-chee. Since the form litchi has been fixed

as a part of the botanical name of the species, and since it is

employed extensively as the common name, it may be well to retain it in

preference to others. The pronunciation ly-chee, which is used in the

region where the fruit is grown, is generally preferred to leechee.

Botanically the plant is Litchi chinensis, Sonn. Nephelium

Litchi, Cambess., is a synonym.

While the litchi is probably best as a fresh fruit, Frank N. Meyer says

that it is considered by some to be more delicious when preserved

(canned) than when fresh; and he adds: "No good dinner, even in

northern China (where the litchi is not grown) is really complete

without some of these delicious little fruits." The dried litchi tastes

something like the raisin. Consul P. R. Josselyn of Canton writes:

"There are two ways of drying litchis, - by sun and by fire. The sun

dried litchi has a finer flavor and commands a better price than the

fire dried fruit." Only two or three varieties are considered suitable

for drying.

Regarding the preserving industry, Josselyn remarks: "It is estimated

by dealers that the annual export of tinned litchis from Canton is

about 3000 boxes, or 192,000 pounds. Each box of preserved litchis

contains 48 tins, weighing 1 catty each. Each tin contains about 28

litchis. There are five large dealers in Canton who make a business of

preserving these litchis. In addition to the preserved litchis exported

from Canton large quantities of the fresh fruit are shipped from the

producing districts surrounding Canton to Hongkong and are there

preserved in tin."

An analysis of the fresh fruit, made in Hawaii by Alice R. Thompson,

shows it to contain : Total solids 20.92 percent, ash 0.54, acids 1.16,

protein 1.15, and total sugars 15.3.

Litchi

Cultivation

In

general it must be considered that the litchi is tropical in its

requirements. It likes a moist atmosphere, abundant rainfall, and

freedom from frosts. It can be grown in subtropical regions, however,

where the climate is moist or if abundant water is supplied, and where

severe frosts are not commonly experienced.

Young plants will

not withstand temperatures below the freezing point. In regions subject

to frost they should, therefore, be given careful protection during the

winter. The mature tree is not seriously injured by several degrees of

frost, but at Miami, Florida, plants six feet high were killed by a

temperature of 26° above zero.

Rev. William N. Brewster of

Hinghua, Fukien, China, describing the conditions under which the trees

are cultivated in that country, says: "They will not flourish north of

the frost line. They are particularly sensitive to cold when young. It

is the custom here to wrap the trees with straw to protect them from

the cold. After the trees are five or six years old they are less

sensitive, and it takes quite a heavy frost to injure them."

Regarding

soil, G. W. Groff of the Canton Christian College writes : "The litchi

seems to do best on dykes of low land where its roots can always secure

all the water needed, and where they are even subjected to periods of

immersion. In some places they grow on high land but not nearly so

successfully." The Rev. Mr. Brewster says on this subject: "The trees

flourish in a soft, moist black soil; alluvium seems best. Near by or

on the bank of a stream or irrigation canal is best, though this is not

essential. Where there is no stream the trees should be watered so

frequently that the ground below the surface is always moist; about

twice a week when rain is not abundant should be enough. After the

young trees are well started, about two or three years old, the

irrigations may be less fre-quent."

These authorities are quoted

to show the conditions under which the litchi is grown in China.

Experience in other countries has shown the tree to be reasonably

adaptable in regard to both climate and soil. While it prefers a humid

atmosphere, it has succeeded in the relatively dry climate of Santa

Barbara, California, without more frequent irrigation than other

fruit-trees. On the plains of northern India, where the atmosphere is

comparatively dry and the annual rainfall about 40 inches, it is

cultivated on a commercial scale. Although the best soil may be a rich

alluvial loam, it has done well in Florida on light sandy loam. It has

not been successful, however, on the rocky lands of southeastern

Florida. Whether these lands are too dry, or whether the litchi

dislikes the large amounts of lime which they contain, cannot be stated

definitely. In undertaking to grow this tree, four desiderata should be

kept in mind : first, freedom from injurious frosts; second, a humid

atmosphere ; third, a deep loamy soil; and fourth, an abundance of

soil-moisture. When one or more of these is naturally lacking, efforts

must be made to correct the deficiency in so far as possible.

Frost-injury can be lessened by protecting the trees; low atmospheric

humidity is not badly prejudicial if the soil is abundantly moist;

sandy soils may be made more suitable by adding humus-forming material;

and a soil naturally dry may be irrigated regularly and frequently.

In

regions where the litchi tree grows to large size, it is not advisable

to space the plants closer than 30 feet apart, and 40 feet is

considered better. In Florida they can be set more closely without

harm; 25 feet will probably be a suitable distance. In localities where

frost protection must be given, it may be desirable to plant the trees

under sheds, and in this case economy will demand that they be crowded

as much as possible. At Oneco, near Bradentown, Florida, E. N. Reasoner

has fruited the litchi very successfully in a region usually considered

too cold for it, by growing it in a shed covered during the winter with

thin muslin to keep off frost, and opened in the summer. If it is

commercially profitable to erect sheds over pineapple-fields, - and it

has proved so in certain parts of Florida, -there seems to be no reason

why it should not be much more profitable to grow the litchi in this

way, in regions where protection from frost is necessary.

The trees

should be planted in holes previously prepared by excavating to a depth

of several feet, and incorporating with the soil a liberal amount of

leaf-mold, well-rotted manure, rich loam, or other material which will

increase the amount of humus. This is, of course, more important where

the soil is light and sandy, as it is in many parts of Florida, than

where the humuscontent is high. Basins may be formed around the trees

to hold water.

Bonavia writes: "As the trees grow, their thalas

or water-saucers should be enlarged and on no account should the fallen

leaves be removed from them, but allowed to decay there and form a

surface layer of leaf-mold. . . . Every hot weather thin layers of

about two or three inches of any other dried leaves should be spread

over the thalas, and allowed to decay there, to be renewed when they

crumple up and decay." This corresponds to the mulching generally

practiced in western countries. It has been remarked by several writers

that the litchi is a shallow-rooted tree, with most of its feeding

roots close to the surface. If this really is the case, mulching will

probably be an essential practice, and deep tilling of the soil will

have to be avoided.

Rev. Mr. Brewster says: "Fertilization is

important. Guano is probably as good as anything. The Chinese use night

soil. They dig a shallow trench around the tree at the end of the roots

and fill it with liquid manure of some sort. This is done about once in

three months." J.E. Higgins, 1 in his bulletin "The Litchi in Hawaii,"

notes that "Some growers prefer to put the manure on as a top dressing

and cover it with a heavy mulch because of the tendency of the litchi

to form surface roots."

The tree requires little pruning.

Higgins says : "The customary manner of gathering the fruit, by

breaking with it branches 10 to 12 inches long, provides in itself a

form of pruning which some growers insist is necessary for the

continued productivity of the tree." But a thorough study has yet to be

made of this subject in the Occident.

Hand-in-hand with the

development of litchi-growing in the American tropics and subtropics

will come the development of new cultural methods. The information at

present available is meager, and too apt to be characterized by the

generalities of the Hindu horticulturist: "Too much manure should not

be applied to newly planted or small trees. As the tree flourishes,

more and more manure should be applied," writes one of them, in a

treatise on litchi-culture. The literature of tropical pomology is

burdened with information of this nature, and the need is for more

specific data based on experience.

1Bull 44, Hawaii Agri. Exp. Sta., 1917.

Litchi

Propagation

Propagation

of the litchi is commonly effected by two means : seed, and

air-layering (known in India as guti). Higgins writes on this subject:

"As

seeds do not reproduce the variety from which they have been taken, and

as the seedlings are of rather slow growth and require many years to

come into bearing, it has for many years been the custom in China, the

land of the litchi, to propagate the best varieties by layering or by

air-layering, a process which has come to be known as 'Chinese

layering' and is applied to many kinds of plants. In air-layering, a

branch is surrounded with soil until roots have formed, after which it

is removed, and established as a new tree. In applying the method to

the litchi, a branch from 3/4 to 1 1/2 inches in diameter is wounded by

the complete removal of a ring of bark just below a bud, where it is

desired to have the roots start. The cut is usually surrounded by soil

held in place by a heavy wrapping of burlap or similar material,

although sometimes a box is elevated into the tree for this purpose.

Several ingenious devices have been made to supply the soil with

constant moisture. Sometimes a can with a very small opening in the

bottom is suspended above the soil and filled with water which passes

out drop by drop into the soil. Again, sometimes the water is

conducted, from a can or other vessel placed above the soil, by means

of a loosely woven rope, one end of which is placed in the water, the

other on the soil, the water passing over by capillarity.

"Air-layering

is commenced at about the beginning of the season of most active

growth, and several months are required for the establishment of a root

system sufficient to support an independent tree. When a good ball of

roots has formed, the branch is cut off below the soil, or the box,

after which it is generally placed in a larger box or tub to become

more firmly established before being set out permanently. At first it

is well to provide some shade and protection from the wind, and it is

often necessary to cut back the top of the branch severely, so as to

secure a proper proportion of stem to root."

Regarding methods of

propagation employed in China, Groff says: "I have never seen a budded

or grafted litchi tree, and I understand it is never done. Litchi trees

are either inarched or layered, the latter being the most common and

most successful. If inarched it is on litchi stock. The common practice

in inarching is to use the Loh Mai Chi variety for cion and the San Chi

for stock."The method of layering mentioned by Groff is that described

above. Inarching is treated in this volume in connection with the

propagation of the mango. It is a tedious process of grafting little

used in America, but more certain than budding and other methods.

Litchi

seeds are short-lived. If removed from the fruit and dried, they retain

their viability not more than four or five days. If they remain in the

fruit, however, and the latter is not allowed to dry, they can be kept

for three or four weeks. In this way they can be shipped to great

distances, or they may be removed from the fruit, packed in moist

sphagnum moss, and allowed to germinate en route. Some of the choice

grafted varieties, such as the Bedana of India, do not produce viable

seeds.

Higgins recommends that the seeds be sown in pots sunk in

well-drained soil. They should be placed hortizontally about 1/2 inch

below the surface of the soil, and after they have germinated the

seedlings should be kept in half-shade.

Attention has recently been

given to the possibility of grafting or budding the litchi on the

longan (Euphoria Longana) and other relatives (see below). Higgins has

successfully crown-grafted the litchi on large longan stocks. He says,

"Repeated experiments with this method have shown that there is no

great difficulty in securing a union of the litchi with the longan. A

noteworthy influence of the stock on the cion should be mentioned here.

The growth produced is very much more rapid than that of the litchi on

its own roots, and in some cases the character of the foliage seems to

undergo a change." Additional experience is required, however, to show

the practical value of the longan and other stocks. The field is an

interesting one, and important results are likely to be secured.

Litchi Yield

And

Season

Seedling

litchis have been known to bear fruit at five years of age. It is

commonly held that they should bear when seven to nine years old. In

some instances, however, trees twenty years old have failed to produce

fruit. Higgins remarks, "Wide variability in the age of coming into

bearing has been noted with seedlings of other tropical fruits,

especially the avocado, but the litchi appears most extreme in this

respect."

Layered plants tend to bear when very young. Sometimes

they will flower a year after planting, and mature a few fruits when

two years old, but three to five years is the age at which they

normally come into bearing.

The litchi is famed as a long-lived

tree. An early Chinese account (not necessarily to be credited)

mentions one which was cut down when it was 800 years old. Bonavia

considered that litchis should remain in profitable bearing for a

century at least.

Mature trees have been found in Hawaii to

yield 200 to 300 pounds of fruit yearly, and crops of 1000 pounds have

been reported. Under good cultural conditions, the tree can be expected

to produce a crop every year. Again quoting Bonavia, it may be said

that the tree "bears annually an abundant crop of fine, well-flavored

and aromatic fruits, which can readily be sent to distant markets.

Instead of being planted by ones or twos, it should be planted by the

thousand."

In picking the fruit, entire clusters are usually

broken off, with several inches of stem attached. If the individual

fruits are pulled off the stems, they are said not to keep well. After

they are picked the fruits soon lose their attractive red color, but

they can be kept for two or three weeks without deteriorating in

flavor. The Chinese sometimes sprinkle them with a salt solution and

pack them in joints of bamboo for shipment to distant markets. At the

Hawaii Experiment Station it was found that "refrigeration, where it is

available, furnishes the best means of preserving the litchi for a

limited period in its natural state. . . . There is no doubt that

refrigeration will provide a very satisfactory method for placing upon

American markets the litchi crop grown in Florida, California, Hawaii,

Porto Rico, or Cuba."

The season of ripening in southern China

is from May to July. In northern India it is slightly earlier. In

Honolulu fresh litchis sell for 50 to 75 cents a pound.

Litchi Pests

And

Diseases

Little

is known regarding the enemies of the litchi in China. Brewster says:

"There is a worm which makes a ring around the trunk under the bark.

When the circle is complete the tree dies; but the bark is broken by

it, and by careful watching this can be prevented before the worm does

serious harm. There is also a sort of mildew upon the leaves in certain

years that does much harm, and the Chinese do not seem to have any way

of dealing with it."

Several insect pests are reported from India. A small brown weevil (Amblyrrhinus poricollis

Boh.), the larvae of a gray-brown moth (Plotheia celtis

Mo.), and the larvae of Thalassodes

quadraria Guen. feed on the leaves. The larvae of Crypto-phlebia carpophaga

Wlsm. attack the fruits. Several species of Arbela (notably A. tetraonis Mo.)

occur as borers on the tree.

It

has been found in Hawaii that the dreaded Mediterranean fruit-fly does

not attack the litchi fruit, except when the shell has been broken and

the pulp exposed. The litchi fruit-worm, the larva of a tortricid moth (Cryptophlebia illepida

Btl.), is said to have caused much damage to the fruit crop at times.

The hemispherical scale (Saissetia

hemispherica Targ.) occasionally attacks weak trees. The

larvae of a moth (Archips

postvittanus Walker) sometimes injure the foliage and

flowers. A disease which has been termed erinose, caused by mites of

the genus Eriophyes,

has been reported from Hawaii, where it has become serious on certain

litchi trees. Spraying with a solution of 10 ounces nicotin sulfate and

1 3/4 pounds whale-oil soap in 50 gallons of water was found to

eradicate the mites.

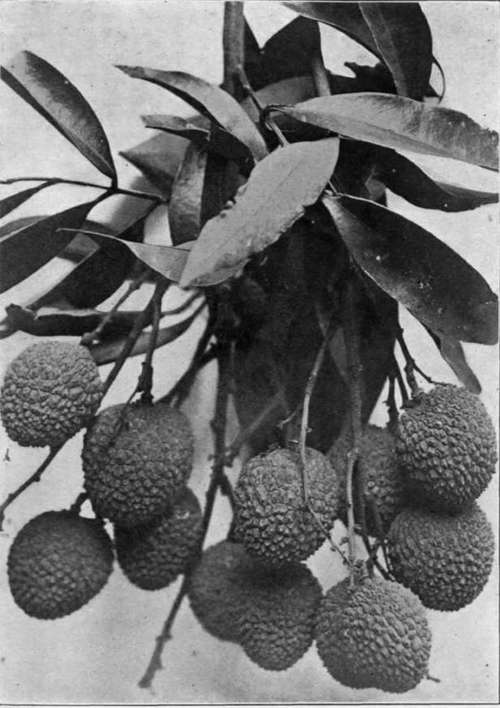

Plate XVII. The litchi, favorite fruit of the Chinese.

Litchi

Varieties

Since

the litchi has been propagated vegetatively from ancient times, it is

natural that many horticultural varieties should be grown at the

present day. Most of these, however, are unknown to the western world.

Recently they have been studied by Groff, and it is to be hoped that

the best will be brought to light, and their successful introduction

into the American tropics realized.

The variety Loh mai chi is

said to be one of the best in the world. It is grown in the vicinity of

Canton. Haak ip is another Canton litchi said to be choice. All

together thirty or forty kinds are reported from this region, some of

them being particularly adapted for drying, others for eating fresh,

and so on.

The varieties cultivated in India are not in all

instances clearly distinguished. The best known is Bedana (meaning

seedless), a medium-sized fruit in which the seed is small and

shriveled. Probably several distinct sorts are known by this name.

McLean's, Dudhia, China, and Rose are other varietal names which appear

in the lists of Indian nurserymen.

Back to

Lychee Page

|

|