From USDA-ARS Subtropical Horticulture Research Laboratory

by Marcia Wood

New Options for Lychee and Longan Fans and Farmers

Published in the May 2004 issue of Agricultural Research magazine

Maybe you've eased into an elegant dinner with a bowl of

chilled lychee soup or lingered over a delicious dessert of lychee ice

cream. This tropical delicacy and its smaller cousin, longan, are

intriguing ARS scientists in Hawai'i. Based at the U.S. Pacific Basin

Agricultural Research Center in Hilo, these ARS experts are

investigating ways to help growers bring more of these exotic fruits to

you.

Hot Bath Foils Insect Foes

Packinghouse

managers must ensure that the fruit they ship isn't harboring live

lychee fruit moths or oriental fruit flies; such stowaways could wreak

agricultural havoc. Irradiation, one option for disinfesting the fruit,

doesn't comply with organic produce standards.

|

Fig. 1

Fruit

flies deposit their eggs through the thin skin of a lychee, causing

juice to ooze out and stain the surface. But lychee is a poor host, and

fruit fly larvae rarely develop in the fruit.

ARS

entomologist Peter Follett and colleagues have developed an alternative

that may help growers expand their markets. The team designed, built,

and tested a twin-tank system that provides a hot-water bath to kill

these insects, followed by a cooling dip to protect the fruit's

delectable qualities.

Fig. 2

Entomologist

Peter Follett (left) and tropical fruit grower Michael Strong installed

the first hot water immersion quarantine treatment unit for lychee and

longan, shown here, at Kahili Farms on the Island of Kauai.

The

unit features submerged, articulated plastic conveyor belts studded

with rubber cleats. These tracks take fruit smoothly in and out of the

heating and cooling tanks. The hot-water tank is calibrated precisely

to meet federal standards. The fruit is submerged for 20 minutes in

water heated to 120°F. The subsequent trip through the cooling tank

helps prevent spoilage. Neither bath harms the pleasant fragrance or

appetizing, slightly firm texture of the fruit.

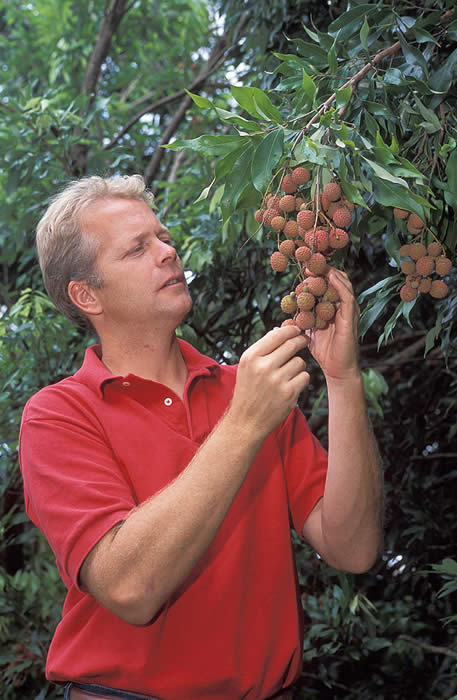

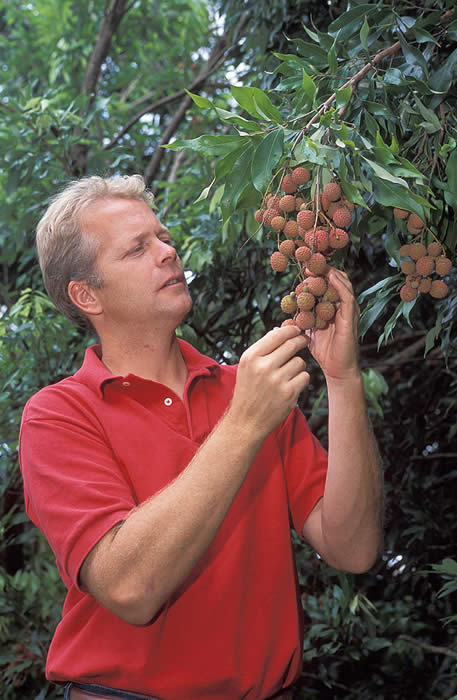

| Fig. 3

Entomologist Peter Follett inspects a panicle of ripening lychee fruit for insect damage. |

Follett

worked with Glenn McHam of MMG Manufacturing, Inc., a Fresno,

California, commercial equipment fabricator; John White, a Fresno-based

designer of agricultural equipment; and Mike Strong, owner of Kahili

Farms, Kilauea, Hawai'i, one of the state's premier growers and packers

of tropical fruit. Kahili Farms, where Follett is fine-tuning and

demonstrating a commercial prototype of the dual-tub process, is in the

final stages of obtaining federal approval for the unit.

Fusing the Ancient With the Modern

Quirks

in timing of lychee and longan flowering and, therefore, fruiting lead

to either boom or bust harvests. Explains ARS horticulturist Tracie

Matsumoto, "Growers are left with too much fruit one year and too

little the next. Ideally, lychee and longan crop yields would be even

and predictable, like apple harvests."

In her Hilo laboratory,

Matsumoto is currently fusing ancient knowledge of Chinese firecracker

ingredients with contemporary discoveries from a plant called thale

cress, Arabidopsis thaliana.

Chinese firecrackers, used for

more than 500 years in religious celebrations and other events, enter

the picture through a fascinating phenomenon noted in Taiwan.

| Fig. 4

Horticulturist Tracie Matsumoto observes a flowering longan tree. |

"Longan

trees growing near temples in that country," says Matsumoto, "were

found to form flowers and then bear fruit shortly after religious

ceremonies in which fireworks were used. This occurred even outside the

typical growing season."

Studies reported in 2000 by Chung-Ruey

Yen of the National Pingtung University of Science and Technology in

Taiwan suggested that a chemical in the ashes of the firecrackers

settled in soil around the trees and triggered flowering.

So how does thale cress fit into the Hawai'i experiments?

Fig. 5

Lychee, Litchi chinensis,

was first introduced into Hawai'i 100 years ago but has been cultivated

in China for nearly 4,000 years. Peeled before eaten, the fruit is

whitish colored, as seen on the right.

Scientists

find thale cress to be a perfect subject for studies of the structure

and function of plant genes. That's because thale cress has very few

genes, making the task significantly less complex. While examining the

plant, researchers at several labs found that one of its genes, flc,

represses flowering. Yet by some unknown mechanism, other thale cress

genes are able to overcome flc to induce the plant to bloom.

"We

want to see whether a repressor gene, like flc in thale cress, exists

in crops such as lychee or longan," explains Matusmoto. "And we want to

find out whether a firecracker chemical somehow interacts with the

repressor gene or other genes to overcome the antiflowering effect.

Once we know that, we might be able to take advantage of this

phenomenon by using a less-explosive version of the fireworks chemical

to cue flowering.

"The lychee and longan industry in Hawai'i is

still quite small, with just a few farms and some productive backyard

trees," she says. "But growers are planting more and more trees. We

want to help these farmers succeed."

| Fig. 6

Horticulturist Tracie Matsumoto collects a sample from a longan tree to isolate the genes involved in flowering. |

Savvy Scientists Share Lychee Expertise

In

the meantime, growers do have some tactics at their disposal to help

them sidestep the problem of unpredictable harvests. "Growing Lychee in

Hawai'i," a popular leaflet published by the University of Hawai'i in

1999, presents guidelines on everything from how to select the

best-performing trees to how to properly prune, fertilize, and irrigate

them.

Francis Zee, horticulturist and curator of ARS's tropical

fruit and nut collection at Hilo, developed some of these techniques in

experiments with lychee trees planted near his laboratory and at an

orchard in Kona, some 120 miles away. Then he teamed with other

specialists in Hawai'i to summarize everyone's recommendations and

present them in the text, tables, and diagrams that make up the

leaflet. "From running a lychee repository for more than a decade,

we've learned a lot of secrets about how to grow this crop," says Zee.

World's Lychees Safeguarded

The

repository that Zee manages serves as a botanical library. Living

examples of lychee, longan, and about a dozen other tropical crops are

preserved for the future and are available today for use by scientists,

growers, and farm advisors. This treasury is part of the nationwide

network of ARS-managed plant collections.

"The lychee and longan

collections here at Hilo are among the best outside of China and

southeast Asia," says Zee. "Some lychees were brought from southern

China in the 1940s by Dr. George Groff, and were donated to us by the

University of Hawai'i, where Groff was a professor.

"Dr. Philip

Ito and I obtained more recent acquisitions, added in the late 1980s

and throughout the 1990s. Before he retired from the university, we

collected in Thailand, China, and Taiwan. We also received additional

specimens by exchanging material with scientists of those countries,"

Zee adds. In 2002, Zee made a preliminary exploration of a wild lychee

forest on China's Hainan Island, southwest of Hong Kong in the Gulf of

Tonkin. He established contacts with some of China's leading

horticulturists and is making plans to return.

The

ARS

repository at Hilo houses many kinds of lychee that are grown in

Hawai'i. These boast a delightful range of shapes, colors, and sizes.

Hak Ip, for example, has thin, smooth, dull-red skin; round- to

heart-shaped fruit; and a single, large seed inside. Chen's Purple has

bright, purplish-red skin and elliptical fruit. No Mai Tsz, the world's

most sought-after lychee because of its exceptional flavor, often has

only a single, shriveled seed inside, nicknamed a "chicken tongue" for

its odd appearance.

The collection also includes India's Bengal;

Kwai May Pink, developed in Australia; and Groff and Kaimana, selected

from other candidate lychee trees for their adaptability to Hawai'i's

soils and climates. All are descendants of China's Litchi chinensis, the source of every domesticated lychee on the planet.

Luscious Longan from Around the Globe

The

longan collection at Hilo is composed of varieties from China, where it

is native, and from other locales. "We have Tiger Eye and Ta u Yu from

China; Si Chompoo and Biew Kiew from Thailand; and Kohala from Hawai'i,"

Zee explains.

"The Thai specimens are more suitable for Hawai'i,

and are more consistently productive here, than those from China,

probably because Thailand's climate is more nearly like that of Hawai'i.

Our collection includes Hawai'i's own, unique longan variety, Egami,

selected by Dr. Ito. We also have the malesianus

subspecies, which bears a soft, soapy-tasting fruit. It has bumpy,

light-mustard-yellow skin instead of the smooth, dark-mustard-brown

peel of its relative, Dimocarpus longan—the domesticated fruit."

Zee

is collaborating with a team led by ARS plant physiologist Paul Moore

at Aiea, Hawai'i, to probe the genetic makeup of lychee and longan. The

intent? To verify work done in 1995 by the repository staff to sort out

exactly who's who among these fruit varieties. That early work

untangled some of the confusion that, understandably, resulted when

traditional names of lychee and longan varieties were translated from

the original Chinese into English. Now, Moore's team is using newer,

more precise DNA-analysis techniques that, earlier, weren't as

available to the repository investigators.

"Collecting,

preserving, and classifying lychee and longan trees is especially

critical," Zee emphasizes. "It's urgent that this happen before old

lychee and longan forests in Asia are destroyed for development or

before older varieties are displaced—in commercial

groves—by new ones.

"With the help of our collaborators

here and overseas, we can continue to expand the collection and

contribute to the knowledge about these fruit species. That way, we can

improve the care of these wonderful gifts that the world has inherited

from China." — By Marcia Wood, Agricultural Research Service

Information Staff.

This research is part of Plant, Microbial,

and Insect Genetic Resources, Genomics, and Genetic Improvement, an ARS

National Program (#301) described on the World Wide Web at

www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

To reach the scientists named in this article,

contact Marcia Wood, USDA-ARS Information Staff, 5601 Sunnyside Ave.,

Beltsville, MD 20705; phone (301) 504-1662, fax (301) 504-1641.

Back to

Lychee Page

Longan Page

|

|