From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Jackfruit

Artocarpus

heterophyllus

Lam.

MORACEAE

The jackfruit,

Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. (syns. A. integrifolius Auct.

NOT L. f.; A

integrifolia L. f.; A.

integra Merr.; Rademachia

integra

Thunb.), of the family Moraceae, is also called jak-fruit, jak, jaca,

and, in Malaysia and the Philippines, nangka; in Thailand, khanun; in

Cambodia, khnor; in Laos, mak mi or may mi; in Vietnam, mit. It is an

excellent example of a food prized in some areas of the world and

allowed to go to waste in others. O.W. Barrett wrote in 1928: "The

jaks . . . are such large and interesting fruits and the trees so

well-behaved that it is difficult to explain the general lack of

knowledge concerning them."

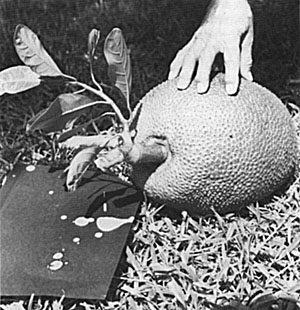

Fig. 15: A heavily fruiting jackfruit (Artocarpus

heterophyllus)

on the grounds of the old Hobson

estate, Coconut Grove. Miami, Eila.

Plate 6: JACKFRUIT, Artocarpus

heterophyllus

Description

The

tree is handsome and stately, 30 to 70 ft (9-21 m) tall, with

evergreen, alternate, glossy, somewhat leathery leaves to 9 in (22.5

cm) long, oval on mature wood, sometimes oblong or deeply lobed on

young shoots. All parts contain a sticky, white latex. Short, stout

flowering twigs emerge from the trunk and large branches, or even from

the soil-covered base of very old trees. The tree is monoecious: tiny

male flowers are borne in oblong clusters 2 to 4 in (5-10 cm) in

length; the female flower clusters are elliptic or rounded. Largest of

all tree-borne fruits, the jackfruit may be 8 in to 3 ft (20-90 cm)

long and 6 to 20 in (15-50 cm) wide, and the weight ranges from 10 to

60 or even as much as 110 lbs (4.5-20 or 50 kg). The "rind' or exterior

of the compound or aggregate fruit is green or yellow when ripe and

composed of numerous hard, cone-like points attached to a thick and

rubbery, pale yellow or whitish wall. The interior consists of large

"bulbs" (fully developed perianths) of yellow, banana-flavored flesh,

massed among narrow ribbons of thin, tough undeveloped perianths (or

perigones), and a central, pithy core. Each bulb encloses a smooth,

oval, light-brown "seed" (endocarp) covered by a thin white membrane

(exocarp). The seed is 3/4 to 1 1/2 in (2-4 cm) long and 1/2 to 3/4 in

(1.25-2 cm) thick and is white and crisp within. There may be 100 or up

to 500 seeds in a single fruit. When fully ripe, the unopened jackfruit

emits a strong disagreeable odor, resembling that of decayed onions,

while the pulp of the opened fruit smells of pineapple and banana.

Origin and Distribution

No

one knows the jackfruit's place of origin but it is believed indigenous

to the rainforests of the Western Ghats. It is cultivated at low

elevations throughout India, Burma, Ceylon, southern China, Malaya, and

the East Indies. It is common in the Philippines, both cultivated and

naturalized. It is grown to a limited extent in Queensland and

Mauritius. In Africa, it is often planted in Kenya, Uganda and former

Zanzibar. Though planted in Hawaii prior to 1888, it is still rare

there and in other Pactfic islands, as it is in most of tropical

America and the West Indies. It was introduced into northern Brazil in

the mid-19th Century and is more popular there and in Surinam than

elsewhere in the New World.

In 1782, plants from a captured

French ship destined for Martinique were taken to Jamaica where the

tree is now common, and about 100 years later, the jackfruit made its

appearance in Florida, presumably imported by the Reasoner's Nursery

from Ceylon. The United States Department of Agriculture's Report on

the Conditions of Tropical and Semitropical Fruits in the United States

in 1887 states: "There are but few specimens in the State. Mr. Bidwell,

at Orlando, has a healthy young tree, which was killed back to the

ground, however, by the freeze of 1886. There are today less than a

dozen bearing jackfruit trees in South Florida and these are valued

mainly as curiosities. Many seeds have been planted over the years but

few seedlings have survived, though the jackfruit is hardier than its

close relative, the breadfruit (q.v.).

In South India, the

jackfruit is a popular food ranking next to the mango and banana in

total annual production. There are more than 100,000 trees in backyards

and grown for shade in betelnut, coffee, pepper and cardamom

plantations. The total area planted to jackfruit in all India is

calculated at 14,826 acres (26,000 ha). Government horticulturists

promote the planting of jackfruit trees along highways, waterways and

railroads to add to the country's food supply.

There are over

11,000 acres (4,452 ha) planted to jack fruit in Ceylon, mainly for

timber, with the fruit a much-appreciated by-product. The tree is

commonly cultivated throughout Thailand for its fruit. Away from the

Far East, the jackfruit has never gained the acceptance accorded the

breadfruit (except in settlements of people of East Indian origin).

This is due largely to the odor of the ripe fruit and to traditional

preference for the breadfruit.

Varieties

In

South India, jackfruits are classified as of two general types: 1)

Koozha chakka, the fruits of which have small, fibrous, soft, mushy,

but very sweet carpels; 2) Koozha pazham, more important commercially,

with crisp carpers of high quality known as Varika. These types are

apparently known in different areas by other names such as Barka, or

Berka (soft, sweet and broken open with the hands), and Kapa or Kapiya

(crisp and cut open with a knife). The equivalent types are known as

Kha-nun nang (firm; best) and Kha-nun lamoud (soft) in Thailand; and as

Vela (soft) and Varaka, or Waraka (firm) in Ceylon.

The

Peniwaraka, or honey jak, has sweet pulp, and some have claimed it the

best of all. The Kuruwaraka has small, rounded fruits. Dr. David

Fairchild, writing of the honey jak in Ceylon, describes the rind as

dark-green in contrast to the golden yellow pulp when cut open for

eating, but the fruits of his own tree in Coconut Grove and those of

the Matheson tree which he maintained were honey jaks are definitely

yellow when ripe. The Vela type predominates in the West Indies.

Firminger

described two types: the Khuja (green, hard and smooth, with juicy pulp

and small seeds); the Ghila (rough, soft, with thin pulp, not very

juicy, and large seeds). Dutta says Khujja, or Karcha, has pale-brown

or occcasionally pale-green rind, and pulp as hard as an apple; Ghila,

or Ghula, is usually light-green, occasionally brownish, and has soft

pulp, sweet or acidulously sweet. He describes 8 varieties, only one

with a name. This is Hazari; similar to Rudrakshi; which has a

relatively smooth rind and flesh of inferior quality.

The

'Singapore', or 'Ceylon', jack, a remarkably early bearer producing

fruit in 18 months to 2 1/2 years from transplanting, was introduced

into India from Ceylon and planted extensively in 1949. The fruit is of

medium size with small, fibrous carpers which are very sweet. In

addition to the summer crop (June and July), there is a second crop

from October to December. In 1961, the Horticultural Research Institute

at Saharanpur, India, reported the acquisition of air-layered plants of

the excellent varieties, 'Safeda', 'Khaja', 'Bhusila', 'Bhadaiyan' and

'Handia' and others. The Fruit Experimental Station at Burliar,

established a collection of 54 jackfruit clones from all producing

countries, and ultimately selected 'T Nagar Jack' as the best in

quality and yield. The Fruit Experimental Station at Kallar, began

breeding work in 1952 with a view to developing short, compact,

many-branched trees, precocious and productive, bearing large, yellow,

high quality fruits, 1/2 in the main season, 1/2 late. 'Singapore Jack'

was chosen as the female parent because of its early and late crops;

and, as the male parent, 'Velipala', a local selection from the forest

having large fruits with large carpers of superior quality, and borne

regularly in the main summer season. After 25 years of testing, one

hybrid was rated as outstanding for precocity, fruit size, off-season

as well as main season production, and yield excelling its parents. It

had not been named when reported on by Chellappan and Roche in 1982. In

Assam, nurserymen have given names such as 'Mammoth', 'Everbearer', and

'Rose-scented' to preferred types.

Pollination

Horticulturists

in Madras have found that hand-pollination produces fruits with more of

the fully developed bulbs than does normal wind-pollination.

Climate

The

jackfruit is adapted only to humid tropical and near-tropical climates.

It is sensitive to frost in its early life and cannot tolerate drought.

If rainfall is deficient, the tree must be irrigated. In India, it

thrives in the Himalayan foothills and from sea-level to an altitude of

5,000 ft (1,500 m) in the south. It is stated that jackfruits grown

above 4,000 ft (1,200 m) are of poor quality and usable only for

cooking. The tree ascends to about 800 ft (244 m) in Kwangtung, China.

Soil

The

jackfruit tree flourishes in rich, deep soil of medium or open texture,

sometimes on deep gravelly or laterite soil. It will grow, but more

slowly and not as tall in shallow limestone. In India, they say that

the tree grows tall and thin on sand, short and thick on stony land. It

cannot tolerate "wet feet". If the roots touch water, the tree will not

bear fruit or may die.

Propagation

Propagation

is usually by seeds which can be kept no longer than a month before

planting. Germination requires 3 to 8 weeks but is expedited by soaking

seeds in water for 24 hours. Soaking in a 10% solution of gibberellic

acid results in 100% germination. The seeds may be sown in situ or may

be nursery-germinated and moved when no more than 4 leaves have

appeared. A more advanced seedling, with its long and delicate tap

root, is very difficult to transplant successfully. Budding and

grafting attempts have often been unsuccessful, though Ochse considers

the modified Forkert method of budding feasible. Either jackfruit or

champedak (q.v.) seedlings may serve as rootstocks and the grafting may

be done at any time of year. Inarching has been practiced and advocated

but presents the same problem of transplanting after separation from

the scion parent. To avoid this and yet achieve consistently early

bearing of fruits of known quality, air-layers produced with the aid of

growth promoting hormones are being distributed in India. In Florida

cuttings of young wood have been rooted under mist. At Calcutta

University, cuttings have been successfully rooted only with forced and

etiolated shoots treated with indole butyric acid (preferably at 5,000

mg/l) and kept under mist. Tissue culture experiments have been

conducted at the Indian Institute of Horticultural Research, Bangalore.

Culture

Soaking

one-month-old seedlings in a gibberellic acid solution (25-200 ppm)

enhances shoot growth. Gibberellic acid spray and paste increase root

growth. In plantations, the trees are set 30 to 40 ft (9-12 m) apart.

Young plantings require protection from sunscald and from grazing

animals, hares, deer, etc. Seeds in the field may be eaten by rats.

Firminger describes the quaint practice of raising a young seedling in

a 3 to 4 ft (0.9-1.2 m) bamboo tube, then bending over and coiling the

pliant stem beneath the soil, with only the tip showing. In 5 years,

such a plant is said to produce large and fine fruits on the spiral

underground. In Travancore, the whole fruit is buried, the many

seedlings which spring up are bound together with straw and they

gradually fuse into one tree which bears in 6 to 7 years. Seedlings may

ordinarily take 4 to 14 years to come into bearing, though certain

precocious cultivars may begin to bear in 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 years. The

jackfruit is a fairly rapid grower, reaching 58 ft (17.5 m) in height

and 28 in (70 cm) around the trunk in 20 years in Ceylon. It is said to

live as long as 100 years. However, productivity declines with age. In

Thailand, it is recommended that alternate rows be planted every 10

years so that 20-year-old trees may be routinely removed from the

plantation and replaced by a new generation. Little attention has been

given to the tree's fertilizer requirements. Severe symptoms of

manganese deficiency have been observed in India.

After

harvesting, the fruiting twigs may be cut back to the trunk or branch

to induce flowering the next season. In the Cachar district of Assam,

production of female flowers is said to be stimulated by slashing the

tree with a hatchet, the shoots emerging from the wounds; and branches

are lopped every 3 to 4 years to maintain fruitfulness. On the other

hand, studies at the University of Kalyani, West Bengal, showed that

neither scoring nor pruning of shoots increases fruit set and that

ringing enhances fruit set only the first year, production declining in

the second year.

Season

In

Asia, jackfruits ripen principally from March to June, April to

September, or June to August, depending on the climatic region, with

some off-season crops from September to December, or a few fruits at

other times of the year. In the West Indies, I have seen many ripening

in June; in Florida, the season is late summer and fall.

Fig. 16: Much white, gummy latex flows from the

jackfruit stalk when

the slightly underripe fruit is

harvested.

Harvesting

Fruits

mature 3 to 8 months from flowering. In Jamaica, an "X" is sometimes

cut in the apex of the fruit to speed ripening and improve flavor.

Yield

In

India, a good yield is 150 large fruits per tree annually, though some

trees bear as many as 250 and a fully mature tree may produce 500,

these probably of medium or small size.

Storage

Jackfruits

turn brown and deteriorate quickly after ripening. Cold storage trials

indicate that ripe fruits can be kept for 3 to 6 weeks at 52°

to

55°F (11.11°-12.78°C) and relative humidity of

85 to 95%.

Pests and Diseases

Principal insect pests in India are the shoot-borer caterpillar, Diaphania caesalis;

mealybugs. Nipaecoccus

viridis, Pseudococcus

corymbatus, and Ferrisia

virgata, the spittle bug, Cosmoscarta relata,

and jack scale, Ceroplastes

rubina. The most destructive and widespread bark borers

are Indarbela tetraonis

and Batocera

rufomaculata. Other major pests are the stem and fruit

borer, Margaronia

caecalis, and the brown bud-weevil, Ochyromera artocarpio.

In southern China, the larvae of the longicorn beetles, including Apriona germarri; Pterolophia discalis, Xenolea tomenlosa asiatica,

and Olenecamptus bilobus

seriously damage the fruit stem. The caterpillar of the leaf webbers,

Perina nuda

and Diaphania bivitralis,

is a minor problem, as are

aphids, Greenidea

artocarpi and Toxoptera

aurantii; and thrips,

Pseudodendrothrips dwivarna.

Diseases of importance include pink disease, Pelliculana (Corticium)

salmonicolor, stem rot, fruit rot and male inflorescence

rot caused by Rhizopus

artocarpi; and leafspot due to Phomopsis artocarpina,

Colletotrichum

lagenarium, Septoria

artocarpi, and other fungi. Gray blight, Pestalotia elasticola,

charcoal rot, Ustilana

zonata, collar rot, Rosellinia

arcuata, and rust, Uredo

artocarpi, occur on jackfruit in some regions.

The

fruits may be covered with paper sacks when very young to protect them

from pests and diseases. Burkill says the bags encourage ants to swarm

over the fruit and guard it from its enemies.

Fig. 17: Dried slices of peeled unripe jackfruit are

commonly marketed

in Southeast Asia

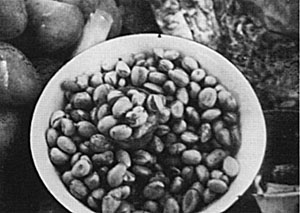

Fig 18: Jackfruit seeds, salvaged from the ripe

fruits, are sold for

boiling or roasting like chestnuts.

Food Uses

Westerners

generally will find the jackfruit most acceptable in the full-grown but

unripe stage, when it has no objectionable odor and excels cooked green

breadfruit and plantain. The fruit at this time is simply cut into

large chunks for cooking, the only handicap being its copious gummy

latex which accumulates on the knife and the hands unless they are

first rubbed with salad oil. The chunks are boiled in lightly salted

water until tender, when the really delicious flesh is cut from the

rind and served as a vegetable, including the seeds which, if

thoroughly cooked, are mealy and agreeable. The latex clinging to the

pot may be removed by rubbing with oil. The flesh of the unripe fruit

has been experimentally canned in brine or with curry. It may also be

dried and kept in tins for a year. Cross sections of dried, unripe

jackfruit are sold in native markets in Thailand. Tender young fruits

may be pickled with or without spices.

If the jackfruit is

allowed to ripen, the bulbs and seeds may be extracted outdoors; or, if

indoors, the odorous residue should be removed from the kitchen at

once. The bulbs may then be enjoyed raw or cooked (with coconut milk or

otherwise); or made into ice cream, chutney, jam, jelly, paste,

"leather" or papad, or canned in sirup made with sugar or honey with

citric acid added. The crisp types of jackfruit are preferred for

canning. The canned product is more attractive than the fresh pulp and

is sometimes called "vegetable meat". The ripe bulbs are mechanically

pulped to make jackfruit nectar or reduced to concentrate or powder.

The addition of synthetic flavoring—ethyl and n-butyl esters

of

4-hydroxybutyric acid at 120 ppm and 100 ppm, respectively greatly

improves the flavor of the canned fruit and the nectar.

If the

bulbs are boiled in milk, the latter when drained off and cooled will

congeal and form a pleasant, orange colored custard. By a method

patented in India, the ripe bulbs may be dried, fried in oil and salted

for eating like potato chips. Candied jackfruit pulp in boxes was being

marketed in Brazil in 1917. Improved methods of preserving and candying

jackfruit pulp have been devised at the Central Food Technological

Research Institute, Mysore, India. Ripe bulbs, sliced and packed in

sirup with added citric acid, and frozen, retain good color, flavor and

texture for one year. Canned jackfruit retains quality for 63 weeks at

room temperature—75° to 80°F

(23.89°-26.67°C),

with only 3% loss of B-carotene. When frozen, the canned pulp keeps

well for 2 years.

In Malaya, where the odor of the ripe fruit is

not avoided, small jackfruits are cut in half, seeded, chilled, and

brought to the table filled with ice cream.

The ripe bulbs, fermented and then distilled, produce a potent liquor.

The

seeds, which appeal to all tastes, may be boiled or roasted and eaten,

or boiled and preserved in sirup like chestnuts. They have also been

successfully canned in brine, in curry, and, like baked beans, in

tomato sauce. They are often included in curried dishes. Roasted, dried

seeds are ground to make a flour which is blended with wheat flour for

baking.

Where large quantities of jackfruit are available, it is

worthwhile to utilize the inedible portion, and the rind has been found

to yield a fair jelly with citric acid. A pectin extract can be made

from the peel, undeveloped perianths and core, or just from the inner

rind; and this waste also yields a sirup used for tobacco curing.

Tender jackfruit leaves and young male flower clusters may be cooked

and served as vegetables.

Food Value Per 100 g of Edible Portion

|

Pulp

(ripe-fresh) |

Seeds (fresh) |

Seeds (dried) |

| Calories

|

98 |

|

|

|

Moisture |

72.0-77.2

g |

51.6-57.77

g |

|

| Protein |

1.3-1.9

g |

6.6 g |

|

| Fat

|

0.1-0.3

g |

0.4

g |

|

| Carbohydrates |

18.9-25.4

g |

38.4

g |

|

| Fiber

|

1.0-1.1

g |

1.5

g |

|

| Ash |

0.8-1.0

g |

1.25-1.50

g |

2.96% |

| Calcium |

22

mg |

0.05-0.55

mg |

0.13% |

| Phosphorus |

38

mg |

0.13-0.23

mg |

0.54% |

| Iron |

0.5 mg |

0.002-1.2

mg |

0.005% |

| Sodium |

2 mg |

|

|

| Potassium |

407

mg |

|

|

| Vitamin

A |

540 I.U. |

|

|

| Thiamine |

0.03

mg |

|

|

| Niacin |

4

mg |

|

|

| Ascorbic

Acid |

8-10 mg |

|

|

The pulp constitutes 25-40% of the fruit's weight.

In general, fresh seeds are considered to be high in starch, low in

calcium and iron; good sources of vitamins B1 and B2.

Toxicity

Even

in India there is some resistance to the jackfruit, attributed to the

belief that overindulgence in it causes digestive ailments. Burkill

declares that it is the raw, unripe fruit that is astringent and

indigestible. The ripe fruit is somewhat laxative; if eaten in excess

it will cause diarrhea. Raw jackfruit seeds are indigestible due to the

presence of a powerful trypsin inhibitor. This element is destroyed by

boiling or baking.

Other Uses

Fruit:

In some areas, the jackfruit is fed to cattle. The tree is even planted

in pastures so that the animals can avail themselves of the fallen

fruits. Surplus jackfruit rind is considered a good stock food.

Leaves:

Young leaves are readily eaten by cattle and other livestock and are

said to be fattening. In India, the leaves are used as food wrappers in

cooking, and they are also fastened together for use as plates.

Latex:

The latex serves as birdlime, alone or mixed with Ficus sap and oil

from Schleichera trijuga Willd. The heated latex is employed as a

household cement for mending chinaware and earthenware, and to caulk

boats and holes in buckets. The chemical constituents of the latex have

been reported by Tanchico and Magpanlay. It is not a substitue for

rubber but contains 82.6 to 86.4% resins which may have value in

varnishes. Its bacteriolytic activity is equal to that of papaya latex.

Wood:

Jackwood is an important timber in Ceylon and, to a lesser extent, in

India; some is exported to Europe. It changes with age from orange or

yellow to brown or dark-red; is termite proof, fairly resistant to

fungal and bacterial decay, seasons without difficulty, resembles

mahogany and is superior to teak for furniture, construction, turnery,

masts, oars, implements, brush backs and musical instruments. Palaces

were built of jackwood in Bali and Macassar, and the limited supply was

once reserved for temples in Indochina. Its strength is 75 to 80% that

of teak. Though sharp tools are needed to achieve a smooth surface, it

polishes beautifully. Roots of old trees are greatly prized for carving

and picture framing. Dried branches are employed to produce fire by

friction in religious ceremonies in Malabar.

From the sawdust of

jackwood or chips of the heartwood, boiled with alum, there is derived

a rich yellow dye commonly used for dyeing silk and the cotton robes of

Buddhist priests. In Indonesia, splinters of the wood are put into the

bamboo tubes collecting coconut toddy in order to impart a yellow tone

to the sugar. Besides the yellow colorant, morin, the wood contains the

colorless cyanomaclurin and a new yellow coloring matter, artocarpin,

was reported by workers in Bombay in 1955. Six other flavonoids have

been isolated at the National Chemical Laboratory, Poona.

Bark: There is only 3.3% tannin in the bark which is occasionally made

into cordage or cloth.

Medicinal Uses:

The Chinese consider jackfruit pulp and seeds tonic, cooling and

nutritious, and to be "useful in overcoming the influence of alcohol on

the system." The seed starch is given to relieve biliousness and the

roasted seeds are regarded as aphrodisiac. The ash of jackfruit leaves,

burned with corn and coconut shells, is used alone or mixed with

coconut oil to heal ulcers. The dried latex yields artostenone,

convertible to artosterone, a compound with marked androgenic action.

Mixed

with vinegar, the latex promotes healing of abscesses, snakebite and

glandular swellings. The root is a remedy for skin diseases and asthma.

An extract of the root is taken in cases of fever and diarrhea. The

bark is made into poultices. Heated leaves are placed on wounds. The

wood has a sedative property; its pith is said to produce abortion.

Related Species

The Champedak,

A. integer

Merr. (syns. A.

champeden Spreng., A.

polyphena Pers.), is also known as chempedak, cempedak, sempedak, temedak in Malaya; cham-pa-da in

Thailand, tjampedak

in Indonesia; lemasa

in the Philippines. The wild form in Malaya is called bangkong or baroh.

The fruit is borne by a deciduous tree, reaching about 60 ft (18 m) in

cultivation, up to 100 or 150 ft (30-45.5 m) in the wild. It is easy to

distinguish from the jackfruit by the long, stiff, brown hairs on young

branchlets, leaves, buds and peduncles. The leaves, often 3-lobed when

young, are obovate oblong or elliptical when mature and 6 to 11 in

(15-28 cm) long. The male flower spikes are only 2 in (5 cm) long and

the fruit cylindrical or irregular, no more than 14 in (35.5 cm) long

and 6 in (15 cm) thick, mustard-yellow to golden-brown, reticulated,

warty, and highly odoriferous when ripe. In fact, it is described as

having the "strongest and richest smell of any fruit in creation." The

rind is thinner than that of the jackfruit and the seeds and

surrounding pulp can be extracted by cutting open the base and pulling

on the fruit stalk. The pulp is deep-yellow, tender, slimy, juicy and

sweet. That of the wild form is thin, subacid and odorless.

The tree

is native and common in the wild in Malaya up to an altitude of 4,200

ft (1,300 m) and is cultivated throughout Malaysia and by many

preferred to jackfruit. It is grown from seed or budded onto

self-seedlings or jackfruit or other Artocarpus species. Seedlings bear

in 5 years. The pulp is eaten with rice and the seeds are roasted and

eaten. The wood is strong and durable and yields yellow dye, and the

bark is rich in tannin.

The Lakoocha,

A. lakoocha

Roxb., is also known as monkey jack or lakuchi in India; tampang and

other similar native names in Malaya; as lokhat

in Thailand. The tree is 20 to 30 ft (6-9 m) tall with deciduous,

large, leathery leaves, downy on the underside. Male and female flowers

are borne on the same tree, the former orange-yellow, the latter

reddish. The fruits are nearly round or irregular, 2 to 5 in (5-12.5

cm) wide, velvety, dull-yellow tinged with pink, with sweet sour pulp

which is occasionally eaten raw but mostly made into curries or

chutney. The male flower spike, acid and astringent, is pickled.

A

native of the humid sub-Himalayan region of India, up to 4,000 ft

(1,200 m), also Malaya and Ceylon, it is sometimes grown for shade or

for its fruit. Seedlings come into production in 5 years. A specimen

was planted at the Federal Experiment Station, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico,

in 1921. There was a large tree in Bermuda in 1918.

The wood, sold as lakuch,

is heavier than that of the jackfruit, similar to teak, durable

outdoors and under water, but does not polish well. It is used for

piles, and in construction; for boats, furniture and cabinetwork. The

bark contains 8.5% tannin and is chewed like betelnut. It yields a

fiber for cordage. The wood and roots yield a dye of richer color than

that obtained from the jackfruit. Both seeds and milky latex are

purgative. The bark is applied on skin ailments. The fruit is believed

to act as a tonic for the liver.

The Kwai Muk,

possibly A.

lingnanensis Merr., was introduced into Florida as A. hypargyraea

Hance, or A.

hypargyraeus

Hance ex Benth. The tree is a slow-growing, slender, erect ornamental

20 to 50 ft (6-15 m) tall, with much milky latex and evergreen leaves 2

to 5 in (5-12.5 cm) long. Tiny male and female flowers are yellowish

and borne on the same tree, the female in globular heads to 3/8 in (1

cm) long.

The fruits are more or less oblate and irregular, 1 to

2 in (2.5-5 cm) wide, with velvety, brownish, thin, tender skin and

replete with latex when unripe. When ripe, the pulp is orange-red or

red, soft, of agreeable subacid to acid flavor and may be seedless or

contain 1 to 7 small, pale seeds. The pulp is edible raw; can be

preserved in sirup or dried. Ripens from August to October in Florida.

The

tree is native from Kwangtung, China, to Hong Kong, and has been

introduced sparingly abroad. It was planted experimentally in Florida

in 1927 and was thriving in Puerto Rico in 1929. It grows at an

altitude of 500 ft (152 m) in China. Young trees are injured by brief

drops in temperature to 28° to 30°F

(-2.22°-1.11°C).

Mature trees have endured 25° to 26°F

(-3.89°-3.33°C)

in Homestead, Florida; have been killed by 20°F

(-6.67°C) in

central Florida.

|

|