From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Jaboticabas

Myrciaria

cauliflora

Berg.

Eugenis cauliflora

DC.

MYRTACEAE

Little known outside their natural range, these members of the

myrtle family, Myrtaceae, are perhaps the most popular native

fruit-bearers of Brazil. Generally identified as Myrciaria cauliflora

Berg. (syn. Eugenia

cauliflora

DC.), the names jaboticaba, jabuticaba or yabuticaba (for the fruit;

jaboticabeira

for the tree) actually embrace 4 species of very similar

trees and fruits: M.

cauliflora,

sabará jaboticaba, also known as jabuticaba

sabará,

jabuticaba de Campinas, guapuru, guaperu, hivapuru, or ybapuru; M. jaboticaba

Berg., great jaboticaba, also known as jaboticaba de Sao Paulo,

jaboticaba do mato, jaboticaba batuba, jaboticaba grauda; M. tenella Berg.,

Jaboticaba macia, also known as guayabo colorado, cambui preto, murta

do campo, camboinzinho; M.

trunciflora Berg., long-stemmed jaboticaba, also called

jaboticaba de Cabinho, or jaboticaba do Pará.

Plate LI: JABOTICABA, Myrciaria

cauliflora

The

word "jaboticaba" is said to have been derived from the Tupi term,

jabotim, for turtle, and means "like turtle fat", presumably referring

to the fruit pulp.

Description

Jaboticaba trees are slow-growing, in M. tenella,

shrubby, 3 1/2 to 4 1/2 ft (1-1.35 m) high; in M. trunciflora,

13 to 23 or rarely 40 ft (4-7 or 12 m); in the other species usually

reaching 35 to 40 ft (10.5-12 m). They are profusely branched,

beginning close to the ground and slanting upward and outward so that

the dense, rounded crown may attain an ultimate spread of 45 ft (13.7

m). The thin outer bark, like that of the guava, flakes off, leaving

light patches. Young foliage and branchlets are hairy.

The

evergreen, opposite leaves, on very short, downy petioles, are

lanceolate or elliptic, rounded at the base, sharply or bluntly pointed

at the apex; 1 to 4 in (2.5-10 cm) long, 1/2 to 3/4 in (1.25-2 cm) in

width; leathery, dark-green, and glossy. Spectacularly emerging from

the multiple trunks and branches in groups of 4, on very short, thick

pedicels, the flowers have 4 hairy, white petals and about 60 stamens

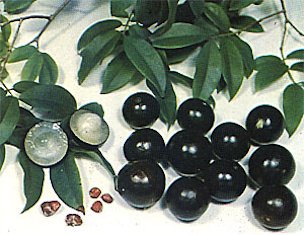

to 1/6 in (4 mm) long. The fruit, borne in abundance, singly or in

clusters, on short stalks, is largely hidden by the foliage and the

shade of the canopy, but conspicuous on the lower portions of the

trunks. Round, slightly oblate, broad-pyriform, or ellipsoid, with a

small disk and vestiges of the 4 sepals at the apex, the fruits vary in

size with the species and variety, ranging from 1/4 in (6 mm) in M.

tenella and from 5/8 to 1 1/2 in (1.6-4 cm) in diameter in the other

species. The smooth, tough skin is very glossy, bright-green,

red-purple, maroon-purple, or so dark a purple as to appear nearly

black, slightly acid and faintly spicy in taste; encloses a gelatinous,

juicy, translucent, all-white or rose-tinted pulp that clings firmly to

the seeds. The fruit has an overall subacid to sweet, grapelike flavor,

mildly to disagreeably resinous, and is sometimes quite astringent.

There may be 1 to 5 oval to nearly round but flattened, hard to tender,

light-brown seeds, 1/4 to 1/2 in (6-12.5 mm) long, but often some are

abortive. The fruit has been well likened to a muscadine grape except

for the larger seeds.

Origin and Distribution

M. cauliflora

is native to the hilly region around Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais,

Brazil, also around Santa Cruz, Bolivia, Asunción, Paraguay,

and

northeastern Argentina. M.

jaboticaba grows wild in the forest around Sao Paulo and

Rio de Janeiro; M.

tenella

occurs in the and zone of Bahia and the mountains of Minas Gerais; in

the states of Sao Paulo, Pernambuco and Rio Grande do Sul; also around

Yaguarón, Uruguay, and San Martin, Peru. M. trunciflora is

indigenous to the vicinity of Minas Gerais.

Jaboticabas

are cultivated from the southern city of Rio Grande to Bahia, and from

the seacoast to Goyaz and Matto Grosso in the west, not only for the

fruits but also as ornamental trees. They are most common in parks and

gardens throughout Rio de Janeiro and in small orchards all around

Minas Gerais. Many cultivated forms are believed to be interspecific

hybrids.

Fig.

101: A jaboticaba tree in full bloom in Brazil is a striking example of

cauliflory (flowers arising from axillary buds on main trunks or older

branches).

An early "hearsay" account of the jaboticabas of Brazil

was published in Amsterdam in 1658. The jaboticaba was introduced into

California (at Santa Barbara) about 1904. A few of the trees were still

living in 1912 but all were gone by 1939. In 1908, Brazil's National

Society of Agriculture sent to the United States Department of

Agriculture plants of 3 varieties, 'Coroa', 'Murta', and 'Paulista'.

The first 2 died soon but 'Paulista' lived until 1917. A Dr. W. Hentz

bought 6 small inarched plants in Rio Janeiro in 1911 and planted them

in City Point, Brevard County, Florida. Only one, variety 'Murta',

survived and he moved it to Winter Haven in 1918. It began fruiting in

1932 and continued to bear in great abundance. Another introduction was

made by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1913 in the form of seeds

collected by the plant explorers, P.H. Dorsett, A.D. Shamel, and W.

Popenoe from marketed fruits in Rio de Janeiro, the best of which was

described as 1 1/2 in (3.8 cm) thick. In 1914, the U.S. Department of

Agriculture received seeds from 40 lbs (28 kg) of fruit purchased in

the public market in Rio de Janeiro, which appeared different from

previous introductions being purple-maroon, round or slightly oblate,

and, at most, not quite 1 in (2.5 cm) in diameter. Plants grown from

these seeds, believed to represent more than one species, were

distributed to Florida, California and Cuba. A seedling of M.

trunciflora from this lot was, up until 1928, grown at the Charles

Deering estate, Buena Vista, Florida, and then transferred to the then

U.S.D.A. Plant Introduction Station (now the Subtropical Horticulture

Research Unit) on Old Cutler Road. It made poor growth in the

limestone, but survived.

In 1918, seeds were presented to the

U.S. Department of Agriculture by the Director of the Escola Agricola

de Lavras in Minas Gerais, and most of the resulting trees were growing

at the Brickell Avenue Garden until 1926 when they were killed by the 3

ft (1 m) of salt water pushed over the garden by the disastrous

hurricane of that year. Dr. David Fairchild rejoiced that, in 1923, he

had set out two of the seedlings at his home, "The Kampong", in Coconut

Grove and these lived; one fruiting for the first time in 1935.

Seedlings of the same lot were successfully grown and fruited heavily

at the Atkins Garden of Harvard University at Soledad, near Cienfuegos,

Cuba.

In 1920, Dr. Fairchild and P.H. Dorsett took several young

trees to Panama and planted them at Juan Mina at sea-level where they

grew well and fruited for many years. Later, jaboticabas were set out

in the new Summit Botanic Garden. Between 1930 and 1940, plants

presumably from the Summit Garden, were installed at the Estacion

Agrícola de Palmira, in southern Colombia.

Seeds were

sent from Washington to the Philippines in 1924. Plants were sent to

Puerto Arturo, Honduras, and transferred to the Lancetilla Experimental

Garden, at Tela, in 1926 and again in 1929. Other plants were

transferred from the Summit Garden in 1928. The trees flourished and

fruited well in Honduras. Dr. Hamilton P. Traub, of the Orlando,

Florida, branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, was establishing

a 2 1/2 acre (nearly 1 ha) experimental block of jaboticabas in 1940

for testing and study. At that time there were only a few bearing trees

in the state. Soon, nurseries began selling grafted trees and they

began appearing in home gardens.

Varieties

M. cauliflora

differs mainly from the other species in the large size of the tree and

of the fruits. The well-known variety 'Coroa' is believed

to belong to this species, also 'Murta'

which has smaller leaves and larger fruits. The latter was among those

sent to California in 1904.

Among commercial sorts in Brazil are:

'Sabará,

a form of M. cauliflora,

is the most prized and most often planted. The fruit is small,

thin-skinned and sweet. The tree is of medium size, precocious, and

very productive. Early in season; bears 4 crops a year. Susceptible to

rust on flowers and fruits.

'Paulista'–fruit

is very large, with thick, leathery skin. The tree is a strong grower

and highly productive though it bears a single crop. Later in season

than 'Sabará' Fruits are resistant to rust. Was introduced

into

California in 1904.

'Rajada'–fruit

very large, skin green-bronze, thinner than that of 'Paulista'. Flavor

is sweet and very good. The tree is much like that of 'Paulista'.

Midseason.

'Branca'–fruit

is large, not white, but bright-green; delicious. Tree is of medium

size and prolific; recommended for home gardens.

'Ponhema'–fruit

is turnip-shaped with pointed apex; large; with somewhat leathery skin.

Must be fully ripe for eating raw; is most used for jelly and other

preserves. Tree is very large and extremely productive.

'Rujada'–fruit

is striped white and purple.

'Roxa'–an

old type mentioned by Popenoe as being more reddish than purple, as the

name (meaning "red") implies.

'Sao Paulo'

(probably M. jaboticaba)–tree

is large-leaved.

'Mineira'–was

introduced into California in 1904.

Pollination

It

has been reported from Brazil that solitary jaboticaba trees bear

poorly compared with those planted in groups, which indicates that

cross-pollination enhances productivity.

Climate

In

Brazil, jaboticabas grow from sea-level to elevations of more than

3,000 ft (910 m). At Minas Gerais, the temperature rarely falls below

33º F (0.56º C). Trees in central Florida have lived

through

freezing weather. In 1917, one very young jaboticaba tree at

Brooksville survived a drop in temperature to 18º F

(-7.78º

C), only the foliage and branches being killed back. In southern

Florida, jaboticabas have not been damaged by brief periods of

26º

F (-3.33º C).

Soil

Jaboticaba

trees grow best on deep, rich, well-drained soil, but have grown and

borne well on sand in central Florida and have been fairly satisfactory

in the southern part of the state on oolitic limestone.

Propagation

Jaboticabas

are usually grown from seeds in South America. These are nearly always

polyembryonic, producing 4 to 6 plants per seed. They germinate in 20

to 40 days.

Selected strains can be reproduced by inarching

(approach-grafting) or air-layering. Budding is not easily accomplished

because of the thinness of the bark and hardness of the wood.

Side-veneer grafting is fairly successful. And experimental work has

shown that propagation by tissue culture may be feasible.

At the

Agricultural Research and Education Center in Homestead, Florida, 6

related genera, including 10 species, were tried as rootstocks in

grafting experiments but none was successful. However, M. cauliflora

scions were satisfactorily joined to rootstock of the same species 1/8

to 1/4 in (3-6 mm) thick, bound with parafilm and grown in plastic bags

under mist.

Culture

Jaboticaba

trees in plantations should be spaced at least 30 ft (9 m) apart each

way. Dr. Wilson Popenoe wrote that in Brazil they were nearly always

planted too close–about 15 ft (4.5 m) apart, greatly

restricting

normal development.

Growth is so slow that a seedling may take 3

years to reach 18 in (45 cm) in height. However, a seedling tree in

sand at Orlando, Florida, was 15 ft (4.5 m) high when 10 years old.

Others on limestone at the United States Department of Agriculture's

Subtropical Horticulture Research Unit were shrubby and only 5 to 6 ft

(1.5-1.8 m) high when 10 and 11 years old. Seedlings may not bear fruit

until 8 to 15 years of age, though one seedling selection flowered in 4

to 5 years. Grafted trees have fruited in 7 years. One planted near

Bradenton, Florida, in bagasse-enriched soil started bearing the 6th

year.

The fruit develops quickly, in 1 to 3 months, after flowering.

Traditionally,

jaboticabas have not been given fertilizer in Brazil, the belief

prevailing that it might be prejudicial rather than beneficial because

of the sensitivity of the root system. Some agronomists have advocated

digging a series of pits around the base of the tree and filling them

with organic matter enriched with 1 part ammonium sulfate, 2 parts

superphosphate, and 1 part potassium chlorate. The pits store and

gradually release the nutrients and the water from the fall rains.

In

1978, E.A. Ackerman of the Rare Fruit Council International, Inc.,

reported on fertilizer experiments with 63 one-year-old and 48 two- and

three-year-old seedlings in containers. Better growth was obtained with

plants in a mixture of equal amounts of acid sandy muck, vermiculite,

and peat, given feedings of 32 g of 14-14-14 slow-release fertilizer

(Osmocote), roughly every 2 1/2 months, and 3 gallons (11.4 liters) of

well water (pH 7.20) by a drip system every 2 days over a period of 18

months, than plants given other treatments. The addition of chelated

iron was of no advantage; chelated zinc retarded growth rate, chelated

manganese stopped growth and caused defoliation. Abundant water was

found to be essential to survival. Irrigation to promote flowering in

the dry season is recommended in Brazil to avoid the detrimental

effects of flowering in the rainy season.

Season

The

time of fruiting varies with the species and/or cultivar and, of

course, the locale. In Rio de Janeiro, M. cauliflora

fruits in May and

M. jaboticaba

in September. If the trees are heavily irrigated in the

dry season, they may bear several crops a year. Trees in southern

Florida usually produce 2 crops a year.

Harvesting and Packing

In

Brazil, jaboticabas harvested in the interior are shipped crudely in

second-hand wooden boxes to urban markets. The toughness of the skin

prevents serious bruising if the boxes are handled with some care.

Keeping Quality

Jaboticabas, once harvested, ferment quickly at ordinary temperatures.

Pests and Diseases

If

the jaboticaba blooms during a period of drought, many flowers

desiccate. If blooming occurs during heavy rains, many flowers will be

affected by rust caused by a fungus. The variety 'Sabará' is

particularly susceptible to attacks of rust on the flowers and fruits.

This is the most serious disease of the jaboticaba in Brazil. The

initial signs are circular spots, at first yellow then dark-brown.

Fruit-eating

birds are very troublesome to jaboticaba growers in Brazil. To protect

the crop, double-folded newspaper pages are placed around individual

clusters and tied at the top. If birds are very aggressive, or if there

are high winds, the paper must be secured with string at the bottom

also. To facilitate this operation, it may be necessary in winter or

early spring to do some pruning to make it easier to climb the trees

and this will result in protecting a larger portion of the crop.

Furthermore,

reducing the number of fruits has the effect of increasing the size of

those that remain. In Florida, raccoons and opossums make raids on

jaboticabas.

Food Uses

Jaboticabas

are mostly eaten out-of-hand in South America. By squeezing the fruit

between the thumb and forefinger, one can cause the skin to split and

the pulp to slip into the mouth. The plant explorers, Dorsett, Shamel

and Popenoe, wrote that children in Brazil spend hours "searching out

and devouring the ripe fruits." Boys swallow the seeds with the pulp,

but, properly, the seeds should be discarded.

The fruits are

often used for making jelly and marmalade, with the addition of pectin.

It has been recommended that the skin be removed from at least half the

fruits to avoid a strong tannin flavor. In view of the undesirability

of tannin in the diet, it would be better to peel most of them. The

same should apply to the preparation of juice for beverage purposes,

fresh or fermented. The aborigines made wine of the jaboticabas, and

wine is still made to a limited extent in Brazil.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Calories |

45.7 |

| Moisture |

87.1 g |

| Protein |

0.11 g |

| Fat |

0.01 g |

| Carbohydrates |

12.58 g |

| Fiber |

0.08 g |

| Ash |

0.20 g |

| Calcium |

6.3 mg |

| Phosphorus |

9.2 mg |

| Iron |

0.49 mg |

| Carotene |

|

| Thiamine |

0.02 mg |

| Riboflavin |

0.02 mg |

| Niacin |

0.21 mg |

| Ascorbic Acid* |

22.7 mg |

Amino Acids: |

|

| Tryptophan |

1 mg |

| Methionine |

|

| Lysine |

7 mg |

*Analyses made in 1955 at the Laboratories FIM de Nutricion, Havana,

Cuba.

|

|

**Others have shown 30.7 mg.

Toxicity

Regular,

quantity consumption of the skins should be avoided because of the high

tannin content, inasmuch as tannin is antinutrient and carcinogenic if

intake is frequent and over a long period of time.

Medicinal Uses

The

astringent decoction of the sun-dried skins is prescribed in Brazil as

a treatment for hemoptysis, asthma, diarrhea and dysentery; also as a

gargle for chronic inflammation of the tonsils. Such use also may lead

to excessive consumption of tannin.

|

|