From the Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Guava

Psidium

guajava L.

The guava, while useful in many ways, is preeminently a fruit for

jelly-making and other culinary purposes. To the horticulturist the

species is admirable as being one of the least exacting of all tropical

fruits in cultural requirements, for it grows and fruits under such

unfavorable conditions, and spreads so rapidly by means of its seeds,

that it has in truth become a pest in some regions. It is a fruit of

commercial importance in many countries, and one whose culture promises

to become even more extensive than it is at present, for guava jelly is

generally agreed to be facile princeps of its kind, and is certain to

find increasing appreciation in the Temperate Zone.

The first account of the guava was written in 1526 by Gonzalo Hernandez

de Oviedo, and published in his "Natural History of the Indies." Oviedo

says:

"The guayabo is a handsome tree, with a leaf like that of the mulberry,

but smaller, and the flowers are fragrant, especially those of a

certain kind of these guayabos; it bears an apple more substantial than

those of Spain, and of greater weight even when of the same size, and

it contains many seeds, or more properly speaking, it is full of small

hard stones, and to those who are not used to eating the fruit these

stones are sometimes troublesome; but to those familiar with it, the

fruit is beautiful and appetizing, and some are red within, others

white; and I have seen the best ones in the Isthmus of Darien and

nearby on the mainland; those of the islands are not so good, and

persons who are accustomed to it esteem it as a very good fruit, much

better than the apple."

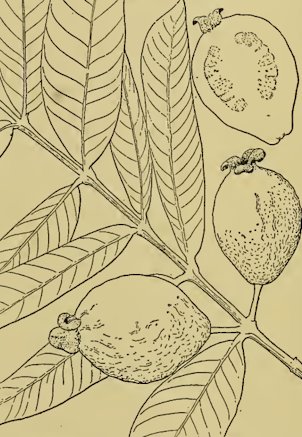

The guava is an arborescent shrub or small tree, sometimes growing to

25 or 30 feet. The trunk is slender, with greenish brown scaly bark.

The young branchlets are quadrangular. The leaves are oblong-elliptic

to oval in outline, 3 to 6 inches long, acute to rounded at the apex,

finely pubescent below, with the venation conspicuously impressed on

the upper surface. Flowers are produced on branchlets of recent growth,

and are an inch broad, white, solitary, or several together upon a

slender peduncle. The calyx splits into irregular segments; the four

petals are oval, delicate in texture. In the center of the flower is a

brush-like cluster of long stamens. The fruit is round, ovoid, or

pyriform, 1 to 4 inches in length, commonly yellow in color, with flesh

varying from white to deep pink or salmon-red. Numerous small,

reniform, hard seeds are embedded in the soft flesh toward the center

of the fruit. The flavor is sweet, musky, and very distinctive in

character, and the ripe fruit is aromatic in a high degree.

Fig. 35. The common guava of the tropics (Psidium Guajava), an American

plant which has become naturalized in southern Asia and elsewhere. (X

1/2)

The native home of the guava is in tropical America. The exact extent

of its distribution in pre-Columbian days is not known. In the opinion

of Alphonse DeCandolle, it occurred from Mexico to Peru. In the former

country the Aztec name for it was xalxocotl, meaning sand-plum,

probably a reference to the gritty character of the flesh. The name

guayaba (whence the English guava) is believed to be of Haitian origin.

The plant was carried at an early day to India, where it has become

naturalized in several places. It is now cultivated throughout the

Orient. In Hawaii it has become thoroughly naturalized. Occasional

specimens are said to be found along the Mediterranean coast of France,

and in Algeria. In short, the guava is well distributed throughout the

tropics and subtropics.

In the United States, the two regions in which guavas can be grown are

Florida and southern California. The plant is said by P. W. Reasoner to

have been introduced into the former state from Cuba in 1847. It is now

naturalized there in many places and cultivated in many gardens. It is

successful as far north as the Pinellas peninsula on the west coast and

Cape Canaveral on the east, but has been grown even farther north. If

frozen down to the ground, the plant sends up sprouts which make rapid

growth and produce fruit in two years. In California the species has

not become common, as it has in Florida, nor is it suited to so wide a

range of territory in the former as in the latter state. Accordingly it

can only be grown successfully in California in protected situations.

At Hollywood, at Santa Barbara, at Orange, and in other localities it

grows and fruits well, although occasional severe frosts may kill the

young branches.

Guayaba is the common name of Psidium guajava throughout the

Spanish-speaking parts of tropical America. The French have adopted

this in the form goyave, the Germans as guajava, and the Portuguese as

goiaba. The latter name is used in Brazil, where the indigenous name

(Tupi language) is araca guacu (large aracu). In the Orient there are

many local names, some of them derived from the American guayaba. The

commonest Hindustani name, amrud, means "pear." The term safari am,

meaning "journey mango," is also current in Hindustani.

The two species Psidium pyriferum and P. pomiferum of Linnaeus are now

considered to be the pear-shaped and round varieties of P. guajava.

They represent two of the many variations which occur in this species.

The pear-shaped forms are often called pear-guava, and the round ones

apple-guava. A large white-fleshed kind was formerly sold by Florida

nurserymen under the name Psidium guineense, and in California as P.

guianense; but it is now known to be a horticultural form of P. guajava, as is also a round, red-fleshed variety introduced into

California under the name P. aromaticum. The true P. guineense, Sw.

(see below) has been itself confused with P. guajava, but can be

distinguished from it by its branchlets, which are

compressed-cylindrical in place of quadrangular, and by the number of

the transverse veins, which is less than in the latter-named species.

The fruit is eaten in many ways, out of hand, sliced with cream,

stewed, preserved, and in shortcakes and pies. Commercially it is used

to make the well-known guava jelly and other products. When well made,

guava jelly is deep wine-colored, clear, of very firm consistency, and

retains something of the pungent musky flavor which characterizes the

fresh fruit. In Brazil a thick jam, known as goiabada, is manufactured

and sold extensively. A similar product is made in Florida and the West

Indies under the name of guava cheese or guava paste. An analysis at

the University of California showed the ripe fruit to contain: Water

84.08 per cent, ash 0.67, protein 0.76, fiber 5.57, total sugars 5.45

(sucrose none), starch, etc., 2.54, fat 0.95.

The guava succeeds on nearly every type of soil. In Cuba it does well

on red clay, in California it has been grown on adobe, and in Florida

it thrives on soils which are very light and sandy. While not strictly

tropical in its requirements, it can scarcely be called subtropical. It

is found in the tropics at all elevations from sea-level to 5000 feet,

and it withstands light frosts in California and Florida. Mature plants

have been injured by temperatures of 28° or 29°, but

the vitality of the guava is so great that it quickly recovers from

frosts which may seem to have damaged it severely. Young plants,

however, may be killed by temperatures of only one or two degrees below

freezing. As regards moisture, writers in India report that the guava

prefers a rather dry climate.

The plants may be set from 10 to 15 feet apart, the latter distance

being preferable. They should be mulched with weeds, grass, or other

loose material immediately after planting. In certain parts of India,

where guava cultivation is conducted commercially on an extensive

scale, it is the custom to set the plants 18 to 24 feet apart. Holes 2

feet wide and deep are prepared to receive the trees. Occasionally the

soil is tilled and once a year each plant is given about 20 pounds of

barnyard manure. During the dry season the orchard is irrigated every

ten days. Very little pruning is done.

Seedling guavas do not necessarily produce fruit identical with that

from which they sprang. It is the custom in most regions to propagate

the guava only by seed, but choice varieties which originate as chance

seedlings can be perpetuated only by some vegetative means of

propagation, such as budding or grafting.

Although the seeds retain their viability for many months, they should

be planted as soon after their removal from the fruit as possible. They

may be sown in flats or pans of light sandy loam and covered to the

depth of 1/4 inch. When the young plants appear they should not be

watered too liberally. After they have made their second leaves, they

may be transferred into small pots. Since they are somewhat difficult

to transplant from the open ground, they had better be carried along in

pots until ready to be planted in the orchard. The proper season for

planting varies in different regions; in India it is said to be July or

August; in California it is April and May; while in Florida October and

March are good months.

Both shield-budding and patch-budding are successful with the guava.

Shield-budding is the better method of the two. P. J. Wester, who says

that the guava was first budded, so far as known, in 1894 by H. J.

Webber at Bradentown, Florida, describes the method in the Philippine

Agricultural Review for September, 1914. He states that budding should

be performed in winter. While it has been done successfully as late as

May, the months from November to April are the best (in the southern

hemisphere the season would, of course, be at the opposite time of

year). The stock-plants should be young; it is best to use them just as

soon as they are large enough to receive the bud. When inserted in old

stocks the buds do not sprout readily. The method of budding is the

same as that described for the avocado and mango. The bud wood should

be so far mature that the green color shall have disappeared from the

bark. The buds should be cut 1 to 1 1/2 inches long.

Patch-budding has been successful in California when large stock-plants

have been used. They should have stems 1 inch in diameter, and the buds

should be cut 1 1/2 inches in length, square or oblong in form.

Propagation by cuttings is also possible if half-ripened wood is used

and bottom-heat is available.

A simple method of propagation, which may be employed when it is

desired to obtain a limited number of plants from a bush producing

fruits of particularly choice quality, is as follows: With a sharp

spade cut into the soil two or three feet from the tree, severing the

roots which extend outward from the trunk. Sprouts will soon make their

appearance. When they are of suitable size they may be transplanted to

permanent positions. They will, of course, reproduce the parent variety

as faithfully as a bud or graft.

The guava is a heavy bearer and ripens its fruit during a long season.

In some regions guavas are obtainable throughout the year, though not

always in large quantities. Seedlings come into bearing at three or

four years of age; budded plants may bear fruit the second year after

they are planted in the orchard. Indian horticulturists state that the

plants bear heavily for fifteen to twenty-five years, and thereafter

gradually decline in production. The guava is not a long-lived plant,

but may live and bear fruit for forty years or more. The season of

ripening in India is November to January; in Florida and the West

Indies it is in late summer and autumn.

The guava is subject to the attacks of numerous insect and fungous

enemies. The list of scale insects injurious to it is a particularly

long one, including numerous species belonging to the genera

Aspidiotus, Ceroplastes, Icerya, Pseudococcus, Pulvinaria, and

Saissetia. All of these can be held in check by the usual means, i.e.,

spraying with kerosene emulsion or some other insecticide, but little

attention is given to this matter in most tropical countries. The

fruit-flies, including species of Anastrepha, Ceratitis, and Dacus,

cause serious trouble in many regions. It is said that 80 per cent of

the guavas produced in Hawaii have in some seasons been infested with

the larvae of the Mediterranean fruit-fly (Ceratitis capitata Wied.).

The guava fruit-rot, a species of Glomerella, is a common fungous

disease in some places. There are other pests, some of them serious,

which the guava-grower may have to combat.

Within the species there evidently exist more or less well-defined

races, each of which includes many seedling variations. Of true

horticultural varieties, propagated by cutting or grafting, there are

as yet practically none. The so-called varieties listed in different

regions are presumably seedling races. Indian nurserymen distinguish a

number of forms, such as "smooth green," "red-fleshed," Karalia,

Mirzapuri, and Allahabad. In the United States, seedlings are offered

of the Allahabad guava, and of forms termed Brazilian, Peruvian, lemon,

pear, smooth green, snow-white, sour, Perico, and Guinea. The number of

such forms which could be listed is considerable. The Guinea variety, a

white-fleshed, sweet-fruited guava with few seeds, has been propagated

in California by budding, but it has not been planted extensively.

Back

to

Guava Page

|

|