From the Manual Of

Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Cherimoya

Annona cherimola Mill.

"Deliciousness itself" is the

phrase Mark Twain used to

characterize the cherimoya. Sir Clements Markham quotes an even more

flattering description :

"The pineapple, the mangosteen,

and the

cherimoya," says Dr. Seemann, "are considered the finest fruits in the

world. I have tasted them in those localities in which they are

supposed to attain their highest perfection, - the pineapple in

Guayaquil, the mangosteen in the Indian Archipelago, and the cherimoya

on the slopes of the Andes, - and if I were called upon to act the part

of a Paris I would without hesitation assign the apple to the

cherimoya. Its taste, indeed, surpasses that of every other fruit, and

Haenke was quite right when he called it the masterpiece of Nature."

The cherimoya at its best

The

cherimoya is essentially a dessert fruit, and as such it certainly has

few equals. Although its native home is close to the equator, it is not

strictly tropical as regards its requirements, being, in fact, a

subtropical fruit, and attaining perfection only where the climate is

cool and relatively dry. At home it grows on plateaux and in mountain

valleys where proximity to the equator is offset by elevation, with the

result that the climate is as cool as that of regions hundreds of miles

to the north or south.

Commercial cultivation of the cherimoya

has been undertaken in a few places. This fruit has not, however,

achieved the commercial prominence which it merits, and which it seems

destined some day to receive.

That it should be unknown in most

northern markets, notwithstanding that it grows as readily in many

parts of the tropics and subtropics as the avocado, can only be due to

the inferiority of the varieties which have been disseminated, to

tardiness in utilizing vegetative means of propagation, and to

insufficient attention to the cultural requirements of the tree. The

best seedling varieties must be brought to light, they must be

propagated by budding or grafting, and a careful study made of

pollination, pruning, fertilization of the soil, and other cultural

details as yet imperfectly understood. There is no reason why, when

this has been done, cherimoya culture should not become an important

horticultural industry in many regions.

Experience in exporting

the fruit from Madeira to London, and from Mexico to the United States,

has shown that it can be shipped without difficulty. The demand for it

in northern markets, once a regular supply is available, is certain to

be keen.

The cherimoya is a small, erect or somewhat spreading

tree, rarely growing to more than 25 feet high; on poor soils it may

not reach more than 15 feet. The young growth is grayish and softly

pubescent. The size of the leaves varies in different varieties; in

some they are 4 to 6 inches long, in others 10 inches. In California a

variety (originally from Tenerife, Canary Islands) with unusually large

leaves has been listed by nurserymen under the name Annona macrocarpa.

In form the leaves are ovate to ovate-lanceolate, sometimes obovate or

elliptic; obtuse or obtusely acuminate at the apex, rounded at the

base. The upper surface is sparsely hairy, the lower velvety tomentose.

The fragrant flowers are about an inch long, solitary or sometimes two

or three together, on short nodding peduncles set in the axils of the

leaves. The three exterior petals are oblong-linear in form, greenish

outside and pale yellow or whitish within; the inner three are minute

and scale-like, and ovate or triangular in outline. As in other species

of Annona, the stamens and pistils are numerous, crowded together on

the fleshy receptacle.

The fruit is of the kind known

technically as a syncarpium. It is formed of numerous carpels fused

with the fleshy receptacle. It may be heart-shaped, conical, oval, or

somewhat irregular in form. In weight it ranges from a few ounces to

five pounds. Sixteen-pound cherimoyas have been reported, but it is

doubtful whether they ever existed in reality. The surface of the fruit

in some varieties is smooth; in others it is covered with small conical

protuberances. It is light green in color. The skin is very thin and

delicate, making it necessary to handle the ripe fruit with care to

avoid bruising it. The flesh is white, melting in texture, and

moderately juicy. Numerous brown seeds, the size and shape of a bean,

are embedded in it. The flavor is subacid, delicate, suggestive of the

pineapple and the banana.

The cherimoya is sometimes confused with other species of Annona. W. E.

Safford, 1 who has studied the botany of this genus thoroughly, writes:

"For

centuries the cherimoya has been cultivated and several distinct

varieties have resulted. One of these has smooth fruit, devoid of

protuberances, which has been confused with the inferior fruit of both Annona glabra and A. reticulata. The

last two species, however, are easily distinguished by their leaves and

flowers; Annona glabra,

commonly known as the alligator apple or mangrove annona, having

glossy laurel-like leaves and globose flowers with six ovate petals,

and A. reticulata

having long narrow glabrate leaves devoid of the velvety lining which

characterizes those of the cherimoya."

1 In Bailey, Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture.

Annona

Cherimola, Mill. is the Annona tripetala of

Aiton; the plant which has been offered in California under the name A. suavissima is a

horticultural form of A.

Cherimola. (The orthography Anona Cherimolia

was used until Safford showed that it is incorrect.)

The

country of origin of the cherimoya remains somewhat in doubt. Alphonse

DeCandolle, after weighing all the available evidence, said, "I

consider it most probable that the species is indigenous in Ecuador,

and perhaps in the neighboring part of Peru." The presence of the fruit

in Mexico and Central America since an early day has led other

botanists to assume that it might also be indigenous in the latter

countries. Recently Safford has re-sifted the evidence and has reached

the conclusion that "De-Candolle is in all probability correct in

attributing it to the mountains of Ecuador and Peru. The common name

which it bears, even in Mexico, is of Quichua origin . . . and

terra-cotta vases modeled from cherimoya fruits have been dug up

repeatedly from prehistoric graves in Peru."

The name by which

this fruit is known in Spanish-speaking countries, cherimoya or

chirimoya, is derived (as mentioned above, quoting Safford) from the

Peruvian name chirimuya, signifying cold seeds. The English frequently

spell the word cherimoyer. The name custard-apple is often used in the

British colonies; its application is not confined, however, to this one

species, but extends to other annonas.

The French use the name cherimolier, or more frequently anone. The name

cherimoya or one of its variants is sometimes applied to other species

of Annona.

From its

habitat in South America, the cherimoya early spread northward into

Mexico; much later it passed into the West Indies, the southern part of

South America, and across the seas to the islands near the African

coast, to the Mediterranean region, and to India, Polynesia, and Africa.

At

present it is naturalized in many parts of Mexico and Central America.

Throughout this region it occurs most abundantly at elevations of 3000

to 6000 feet, occasionally ascending (in Guatemala) to 8000 feet. On

the seacoast it is not successful as a fruit-tree, and is rarely grown.

The regions which produce the finest cherimoyas in Mexico lie at

elevations of 5000 to 6000 feet and are characterized by comparatively

dry cool climates. Excellent cherimoyas are grown at Queretaro and in

the vicinity of Guadalajara. The fruit is highly esteemed in the

markets of Mexico City, where it sells at high prices. While not grown

commercially on a scale comparable with the avocado, its culture in

certain regions is important, and regular shipments are made to the

principal markets of the country.

In Jamaica, where the

cherimoya was introduced by Hinton East in 1785, there are now many

trees in the mountainous parts of the island. The fruit is highly

esteemed in the markets of Kingston. In Cuba it is almost unknown.

There are a few trees in Oriente Province and perhaps elsewhere, but

the markets of Habana are not familiar with it. It may be mentioned

that Annona reticulata is often called cherimoya in Cuba, which has led

some writers to assume wrongly that the true cherimoya is commonly

cultivated in the island.

In Argentina, cherimoya culture is

conducted commercially in several places, notably the Campo Santo

district in the province of Salta. The fruit is shipped to Buenos

Aires, where it is marketed at very profitable prices. In Brazil it is

not commonly grown; in fact it is not known in most parts of the

Republic.

In 1897 M. Grabham wrote a short article in the

Journal of the Jamaica Agricultural Society on the cultivation of the

cherimoya in Madeira. He asserted that "many of the estates on the warm

southern slopes of the island, formerly covered with vineyards, have

now been systematically planted with the cherimoya" and went on to

state that "the fruits vary in weight between three and eight pounds,

exceptionally large ones may reach 16 pounds and over." This article,

which has been widely quoted, has been responsible for the current

belief that cherimoya culture in Madeira is more extensive than in any

other part of the world, and that exceptionally fine varieties have

been developed.

Charles H. Gable, an American

entomologist and horticulturist who worked in the island during 1913

and 1914, has dispelled these illusions. Gable writes:

"I found the

cherimoya industry in Madeira very primitive indeed. No effort has been

made to commercialize the growing of this fruit. Most of the trees are

volunteers which have sprung up from dropped seeds, or else they have

been planted for shade, with perhaps a vague notion that they might

some day produce fruit. ... I do not know any one in Madeira (and I

have been over the entire island) who has more than a dozen trees in

bearing, and only a few have that many. Most of the important islanders

have at least one tree. ... At least 95 per cent of all those on the

island are seedlings. Occasionally old trees are top-worked by a method

of cleft-grafting, but this is not highly successful. . . . There is no

uniformity in the quality of the fruits. Every gradation is found

between smooth-surfaced and very rough fruits. In those which resemble

each other externally there may be great differences in quality,

acidity, number of seeds, and other characteristics. I never got so I

felt competent to pick out a good fruit in the market. . . . The rough

type attains the greatest size. The largest specimen I was able to find

weighed three and a half pounds. ... I hesitate to make an estimate,

but I do not believe more than a thousand dozen fruits are exported

from the island in a year. . . . The trees receive no intentional

cultivation. Vegetables are often planted beneath them. A species of

scale insect and the mealy bug infest many of them. . . . The trees do

not seem to do well above 800 feet elevation. The ripening season is

from the last of November until the first of February."

In the

Canary Islands the cherimoya is not cultivated commercially, but it is

grown on a limited scale. Georges V. Perez writes: "Ever since I can

remember it has been cultivated in the gardens of Orotava as a

delicious and perhaps unequalled tropical fruit."

In the

Mediterranean region there are several localities in which it can be

grown successfully. A. Robertson-Prosch-owsky, who has experimented

with many tropical and subtropical plants at Nice, France, finds that

the fruits, if caught by cold weather before they mature, do not ripen

perfectly. If, however, the winter is mild and warm they may mature

satisfactorily, even if very late. Robertson-Proschowsky believes that

the cherimoya is well suited for cultivation in sheltered spots along

the Cote d'Azur (French Riviera), and he recommends it as a fruit

worthy of serious attention in that region.

It is cultivated on

a limited scale in southern Spain and in Sicily. L. Trabut 1 of Algiers

writes: "Lovers of the anona

will find in the markets of Algiers,

during November and December of each year, a few good fruits which are

sold at 30 centimes to 1 franc each. These fruits come from gardens

along the western coast, where there are some magnificent trees." He

further says: "It seems evident that the moment has come to extend

cherimoya culture. It is not more difficult than orange culture, and at

present promises to be more remunerative." Trabut recommends that the

tree be planted in Algeria on the coast only, since the climate of the

interior is too cold.

The cherimoya has been planted in

several parts of India but has not become a common fruit in that

country. H. F. Macmillan says that it is "now cultivated in many

up-country gardens in Ceylon." It was introduced into the latter island

as late as 1880. In parts of Queensland, Australia, it is successfully

grown.

In Hawaii it has become well established. Vaughan

MacCaughey 1 says: "It was introduced into the Hawaiian Islands in very

early times, and is now naturalized, particularly in certain parts of

the Kona and Kau districts on the island of Hawaii." He adds that

cherimoyas are rarely seen in the markets of Honolulu, but that trees

are found in gardens throughout the city.

1 Bull. 24, Service Botanique, Algeria.

Nowhere

in Florida is the cherimoya a common fruit. Trees in limited numbers

have been planted in several parts of the state, notably in the Miami

region. While they grow vigorously they do not fruit so freely, nor is

the fruit of such good quality, as in many other countries. It is

probable that the climate of south Florida is too tropical for this

species.

As regards California, it is believed that the

first cherimoyas planted in the state were brought from Mexico by R. B.

Ord of Santa Barbara in 1871. A few years later Jacob Miller planted a

small grove on his place at Hollywood, near Los Angeles. In the

relatively short time since these first plantings were made, the

cherimoya has become scattered throughout southern California, from

Santa Barbara to San Diego. The climate and soil of the foothill

regions seem to be peculiarly suited to it. A few commercial plantings

have been made, notably at Hollywood, but since they are composed

entirely of seedlings they have not proved remunerative. Had budded

trees of desirable varieties been planted, the results would have been

different. In the largest commercial planting, that of A. Z. Taft at

Hollywood, one seedling, more productive than the remainder, produced

one year about one-fourth the entire crop of the grove. Out of eighty

trees comprised in the planting, only five produced more than a few

fruits. By top-working the unproductive trees to a productive and

otherwise desirable variety, they could have been made valuable.

For sheltered situations throughout the foothill tracts of southern

California, cherimoya culture holds great promise.

1 Torreya, May, 1917.

As soon as budded or grafted trees of good varieties are available,

many small orchards should be established quickly.

The

cherimoya is commonly eaten fresh : rarely is it used in any way except

as a dessert fruit. Alice R. Thompson, who has analyzed the fresh fruit

in Hawaii, finds that it contains : Total solids, 33.81 per cent, ash

0.66 per cent, acids 0.06 per cent, protein 1.83 per cent, total sugars

18.41 per cent, fat 0.14 per cent, and fiber 4.29. It will be noted

that the sugar-content is high, while that of acids is low. The

percentage of protein is higher than in many other fruits.

Cultivation

The

climatic requirements of the cherimoya have been indicated in the

discussion of the regions in which it is cultivated. It is essentially

a subtropical fruit, and in the tropics succeeds only at elevations

sufficiently great to temper the heat. It thrives best in regions where

the climate is relatively dry. In the southern part of Guatemala, where

the annual rainfall is about 50 inches but where there is a long dry

season, it is extensively grown and the fruit is of excellent quality;

but in the northern part of the same country, where the rainfall is

nearly 100 inches, distributed throughout the year, the tree cannot be

grown successfully. In the highlands of Mexico it is best suited where

the climate is dry, free from extremes both of heat and cold, and where

abundant water is available for irrigating. The climate of southern

California, except in sections subject to severe frosts, seems almost

ideal for it. In many places frost is the limiting factor, for the

cherimoya, while the hardiest of its genus, does not endure

temperatures lower than 26° or 27° above zero without

serious

injury. Young plants will, of course, be hurt by mild frosts which

mature trees would ignore; in fact, temperatures lower than 29°

or

30° are likely to injure them.

Like other annonas,

the cherimoya prefers a rich loamy soil. It can be grown, however, on

soils of many different types.

In

California it has done well on heavy clay (almost adobe), while in

Florida it makes satisfactory growth on shallow sandy soils. H. F.

Schultz considers the ideal soil to be a fairly rich, loose sandy loam,

underlaid with gravel at a depth of two to three feet. He says: "Some

of the best Campo Santo and Betania (Argentina) groves are located on

such land, which is furthermore characterized by a liberal outcropping

of scattered rocks." Carlos Werckle states that the tree does well in

Costa Rica on "stony cliffs." He reports that it is more productive

under these conditions than when grown on richer soil, and himself

considers it partial to mountain slopes on which there is much

limestone rock.

Experience in California has shown that the

cherimoya requires cultural treatment similar to that given the citrus

fruits. Budded trees should be planted in orchard form about 20 to 24

feet apart; seedlings about 30 feet apart, since they grow to larger

size. Irrigations, followed by thorough cultivation of the soil, are

given at intervals of two weeks to one month. While the trees are

young, more frequent irrigations are necessary. In Argentina, according

to H. F. Schultz, it is the custom to irrigate the trees at intervals

of six to twelve days. In Mexico two weeks is considered the proper

interval.

In California, stable manure has been used for

young trees with excellent results, and occasionally for bearing

groves. Little attention has been devoted to the subject; hence it is

not possible to give specific directions for the use of fertilizers. A

writer in the Queensland Agricultural Journal recommends that each tree

be given annually 1 to 3 pounds of superphosphate, 2 to 6 pounds of

meat-works manure with blood, and 1 to 2 pounds of sulfate of potash.

The

pruning of cherimoyas has received little attention as yet in the

United States. In Argentina it is considered that trees which are kept

low and compact are both more precocious and longer lived than those

which are tall and open in habit.

In Guatemala the most productive

trees are usually those which have been cut back heavily. It is

possible that fruitfulness can be increased by severe pruning. The

matter deserves careful investigation. The tree being semi-deciduous,

pruning should be done after the leaves have dropped and before the new

foliage makes its appearance.

Propagation

In

many regions seed-propagation is the only method which has been used

with this plant. In the United States, in Madeira, in Algeria, and in

the Philippines, cherimoyas have been grafted and budded successfully;

one or the other of these methods should be employed to perpetuate

choice varieties.

If kept dry the seeds will retain their

viability several years. Given warm weather or planted under glass,

they will germinate in a few weeks. Under glass they may be sown at any

time of the year; if in open ground, they should be planted only in the

warm season. Seeds should be sown in flats of light porous soil

containing an abundance of humus, and should be covered to a depth of

not more than 3/4 inch. When the young plants are three or four inches

high, they may be transferred into three-inch pots. Good drainage must

be provided, and they should not be watered too copiously. When eight

inches high they may be shifted into larger pots, or set out in the

open ground. In the latter case, they must have careful attention, and,

preferably, shade, until they have become well established.

For

stock-plants on which to bud or graft the cherimoya, several species of

Annona

have been employed. A.

reticulata, A. glabra, and A. squamosa

are all recommended by P. J. Wester. In Florida A. squamosa has

proved

to be a good stock when a dwarf tree is desired; A. glabra tends to

outgrow the cion. In California, seedling cherimoyas as stock-plants

have given the best results.

Shield-budding has worked very

satisfactorily in the United States. In several other regions

horticulturists have found grafting more successful. Budding is best

done at the beginning of the growing season, when the sap is flowing

freely. Stock-plants should be 3/8 to 1/2 inch in diameter.

Well-matured budwood from which the leaves have dropped is preferable,

and it should be gray, not green, in color. The buds should be cut l

1/2 inches in length, and should be inserted exactly as in budding

avocados or mangos. Waxed tape, raffia, and soft cotton string have

proved satisfactory for tying. Three or four weeks after insertion of

bud, the wrapping should be loosened and the stock lopped at a point 5

or 6 inches above the bud. Wrapping should not be removed entirely

until the bud has made a growth of several inches.

For grafting,

two-year-old seedlings are to be preferred (for budding they may be

somewhat younger). The cleft-graft is the method usually employed. The

cion should be well-matured wood from which the leaves have dropped. C.

H. Gable wrote from Madeira in 1914: "I have been surprised to find

how easily the annona is grafted. My first few efforts were not very

successful, but later I grafted them in all sizes from seedlings

smaller than a lead pencil to old trees, and more than 90% have grown

beautifully." Gable found it advisable after making the graft to paint

the cion and the top of the stock (around the cleft) with melted wax,

to prevent evaporation.

Old seedling trees can be top-worked

without difficulty. For this purpose cleft-grafting is used more

commonly than any other method.

The pollination of the

cherimoya has been investigated in Florida by P. J. Wester, and in

Madeira by C. H. Gable. It has been thought that the scanty

productiveness of many trees might be due to insufficient pollination,

and the investigations tend to confirm this belief. Gable reports that

normally in Madeira not more than 5 per cent of the flowers produced

develop into fruits. By hand-pollinating them, however, he was able to

obtain thirty-six fruits from forty-five flowers.

After carrying on

pollination experiments in Florida during several years, P. J. Wester 1

wrote: "The investigations indicate that the flowers of the cherimoya,

the sugar-apple, the custard-apple and the pond-apple are proterogynous

and entomophilous, though the pollinating agent of the last-named

species has not been detected." A proterogynous plant, it may be

remarked, is one in which the pistils are receptive before the anthers

have developed ripe pollen, cross-pollination being therefore

necessary, and some outside agency being required to effect it. In the

case of the annonas

the work is done by insects; hence the plants are

termed entomophilous.

The pollination of the closely allied

Asimina

triloba is thus described by Delpino: 2

"The stamens project in

the center of the pendulous protogynous (proterogynous) flower as a

hemispherical mass, from the middle of which a few styles with their

stigmas project. In the first (female) stage of anthesis the three

inner petals lie so close to the stamens that insect visitors (flies)

cannot suck the nectar secreted at the bases of the former without

touching the already mature stigmas. In the second (male) stage the

stigmas have dried up and the inner petals have raised themselves, so

that the anthers, - now covered with pollen, - are touched by insects

on their way to the nectar. Cross-pollination of the younger flowers is

therefore effected by transference from the older ones. Wester

concluded that one cause of the unproductiveness of the cherimoya in

Florida was the scarcity of pollinating insects. Even under the same

conditions of environment, however, there are marked differences in

productiveness among seedling trees. The subject deserves further

investigation. Productive varieties especially should be studied, to

determine whether or not they differ in any way from the typical less

fecund form in manner of pollination.

1 Bull. of the Torrey Bot. Club, 37,

1910.

2 Paul Knuth, Handbook of Flower

Pollination.

Crop

Seedling

cherimoyas, when grown under favorable cultural conditions, begin to

bear the third or fourth year after planting. Most of them, even at

fifteen or twenty years of age, do not produce annually more than a

dozen good fruits. Occasional trees are more satisfactory in this

respect, and it is such trees which should be propagated by budding.

The writer has observed one small tree in Guatemala which bore

eighty-five fruits in a single season, and C. H. Gable found a tree in

Madeira which bore three hundred.

In California the main

season for cherimoyas is spring, usually March and April; but sometimes

a few fruits mature in late autumn. In Argentina the season is February

to July. Felix Foex states that there are ripe cherimoyas in Mexico

throughout the year, owing to the presence of trees at different

elevations. From personal observation the writer ventures to doubt

whether this all-year season is a fact; in any event, they are not

abundant during the entire year. In Madeira the fruit begins to ripen

about the end of November and continues in season until early in

February.

When fully mature or "tree-ripe," the fruits are

picked and laid away to soften. If, however, they are to be shipped to

distant markets they are packed as soon as removed from the tree, and

dispatched at once so that they will reach their destination before

they have become soft. When fully mature and ready to pick, they

usually have a yellowish tinge. In Mexico they are packed for shipment

in baskets, using hay or straw as a cushion. According to H. F.

Schultz, the same method is used in Argentina, where twelve to fifteen

dozen fruits are packed in a basket. Good ventilation should be

insured, and the fruits should not be wrapped in paper. Cherimoyas

exported from Madeira to London net the growers $1.00 to $1.20 a dozen.

In Argentina the average price to growers is $2.20 a dozen.

Pests and

Diseases

Although

the cherimoya has up to the present suffered little from the attacks of

insect and other pests in California and Florida, it is far from being

exempt from them in regions where it has been grown extensively for a

long period. In Hawaii, Pseudococcus

filamentosus Cockerell is a

serious enemy. Several other coccids have also been reported on the

cherimoya, Aulacaspis

miranda Cockerell and Ceropute

yuccoe Coquillet

are two which are mentioned from Mexico. Certain of the fruit-flies

(Trypetidse)

are known to attack the fruits of the cherimoya.

Throughout the warmer parts of America there are small chalcid flies,

related to the wheat-joint worm and the grape-seed chalcid, which

infest the seeds of annonaceous fruits. Bephrata cubensis

Ashm. has

been reported as attacking the cherimoya in Cuba. These insects are

serious pests. In Argentina the attacks of borers are said to reduce

the life of the average tree by half, making it thirty in place of

sixty years.

Varieties

While there are

important differences among seedling cherimoyas, affecting not only the

productiveness and foliage of the tree but also the size, form,

character of surface, color, quality, and number of seeds of the fruit,

few named varieties have as yet been propagated. In the Pomona College

Journal of Economic Botany (May, 1912) the author has described two,

viz., Mammillaris and Golden Russet, which have been propagated in

California on a limited scale. Neither of these, however, merits

extensive cultivation; hence the descriptions will not be included in

this work. It seems desirable, however, to repeat the botanical

classification of seedling cherimoyas published by W. E. Safford in the

Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. This comprises the following five

forms :

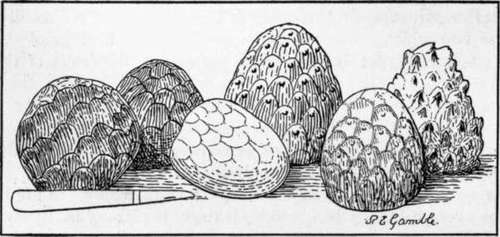

Finger-printed (botanically known as forma

impressa).- Called in Costa Rica anona de dedos pintados.

The fruit is

conoid or subglobose in shape, and has a smooth surface covered with

U-shaped areoles resembling finger-prints in wax. Many seedlings of

this type are of good quality, and contain few seeds.

Smooth

(forma loevis).-

Called chirimoya lisa in South America and anon in

Mexico City. This form is often mistaken for Annona glabra and A.

reticulata because of the general appearance of the fruit

and on

account of the name anon, which is also applied to A. reticulata. One

of the finest types of cherimoya.

Fig. 24. Seedling cherimoyas, showing some of the common types. (X 1/5)

Tuberculate (forma

tuberculata).

- One of the commonest forms. The fruit is heart-shaped and has

wart-like tubercles near the apex of each areole. The Golden Russet

variety belongs to this group.

Mammillate (forma

mamillata).

- Called in South America chirimoya de tetillas. Said to be common in

the Nilgiri hills in southern India, and to be one of the best forms

grown in Madeira.

Umbonate (forma umbonata).

- Called chirimoya de puas and anona picuda in Latin America. The skin

is thick, the pulp more acid than in other forms, and the seeds more

numerous. The fruit is oblong-conical, with the base somewhat

umbilicate and the surface studded with protuberances, each of which

corresponds to a component carpel.

Hybrids between the cherimoya and the sugar-apple (Annona squamosa)

have been produced in Florida by P. J. Wester and Edward Simmonds. The

aim has been to develop a fruit having the delicious flavor of the

cherimoya, yet adapted to strictly tropical conditions. Some of the

hybrids have proved to be very good fruits, and further work along this

line is greatly to be desired. Wester calls this new fruit atemoya.

Hybrids between it and the sugar-apple, the bullock's-heart, and the

pond-apple have been obtained by him in the

Philippines.

Back to

Cherimoya Page

|

|