From Lost Crops of the Incas:

little-known plants of the Andes with promise for worldwide cultivation

by National Research Council

(U.S.) Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation

Cherimoya

Universally regarded as a premium fruit, the cherimoya (Annona cherimola)

has been called the “pearl of the Andes,” and the “queen of subtropical

fruits.” Mark Twain declared it to be “deliciousness itself!”

In the past, cherimoya (usually pronounced chair-i-moy-a in English)

could only be eaten in South America or Spain. The easily bruised, soft

fruits could not be transported any distance. But a combination of new

selections, advanced horticulture, and modern transportation methods

has removed the limitations. Cushioned by foam plastic, chilled to

precise temperatures, and protected by special cartons, cherimoyas are

now being shipped thousands of kilometers. They are even entering

international trade. Already, they can be found in supermarkets in many

parts of the United States, Japan, and Europe (mainly France, England,

Portugal, and Spain).

Native to the Ecuadorian Andes, the cherimoya is an important backyard

crop throughout much of Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia, and

Peru. Chileans consider the cherimoya to be their “national fruit” and

produce it (notably in the Aconcagua Basin) on a considerable

commercial scale. In some cooler regions of Central America and Mexico,

the plant is naturalized and the fruit is common in several locales. In

the United States, the plant produces well along small sections of the

Southern California coast where commercial production has begun.

Outside the New World, a scattering of cherimoya trees can be found in

South Africa, South Asia, Australasia, and around the Mediterranean.

However, only in Spain and Portugal is there sizable production. In

fruit markets there, cherimoyas are sometimes piled as high as apples

and oranges.

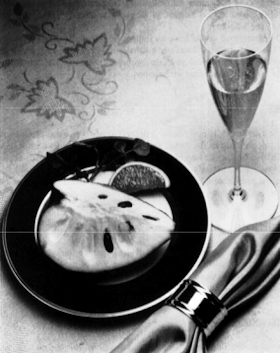

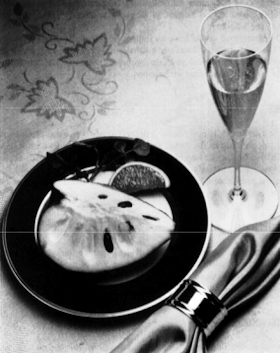

A good cherimoya certainly has few equals. Cutting this large, green,

heart- shaped fruit in half reveals white flesh with black seeds. The

flesh has a soft, creamy texture. Chilled, it is like a tropical

sherbet—indeed, cherimoya has often been described as “ice-cream

fruit.” In Chile, it is a favorite filling for ice-cream wafers and

cookies. In Peru, it is popular in ice cream and yogurt.

World demand is strong. In North America and Japan, people pay more for

cherimoya than for almost any other fruit on the market. At present,

premium cherimoyas (which can weigh up to 1 kg each) are selling for up

to $20 per kg in the United States and more than $40 per kg in Japan.

Despite such enormous prices, sales are expanding. In four years, the

main U.S. supplier's weekly sales have increased from less than 50 kg a

week to more than 5,000 kg a week.

Today, the crop is far from reaching its potential peak. Modern

research is only now being applied—and in only a few places,

principally Chile, Argentina, Spain, the Canary Islands, and

California. Nonetheless, even limited research has produced a handful

of improved cultivars that produce fruit of good market size (300–600

g), smooth skin, round shape, good flavor, juiciness, low seed ratio,

resistance to bruising, and good storage qualities. With these

attributes, larger future production and expanded trade seem inevitable.

But growing cherimoyas for commercial consumption is a daunting

horticultural challenge. In order to produce large, uniform fruit with

an unbroken skin and a large proportion of pulp, the grower must attend

his trees constantly from planting to harvest; each tree must be

pruned, propped, and—at least in some countries—each flower must be

pollinated by hand.

Nevertheless, the expanding markets made possible by new cultivars and

greater world interest in exotic produce now justify the work necessary

to produce quality cherimoya fruits on a large scale. Eventually,

production could become a fair-sized industry in several dozen

countries.

PROSPECTS

The Andes.

Although cherimoyas are found in markets throughout the Andean region,

there has been little organized evaluation of the different types, the

horticultural methods used, or the problems growers encounter. Given

such attention, as well as improved quality control, the cherimoya

could become a much bigger cash crop for rural villages. With suitable

packaging increasingly available, a large and lucrative trade with even

distant cities seems likely. Moreover, increased production will allow

processed products—such as cherimoya concentrate for flavoring ice

cream—to be produced both for local consumption and for export.

Other

Developing Areas. Everywhere these fruits are grown, they

are immediately accepted as delicacies. Thus, the cherimoya promises to

become a major commercial crop for many subtropical areas. For example,

it is likely to become valuable to Brazil and its neighbors in South

America's “southern cone,” to the highlands of Central America and

Mexico, as well as to North Africa, southern and eastern Africa, and

subtropical areas of Asia.

Cherimoya has been grown for centuries in the highlands of Peru and

Ecuador, where it was highly prized by the Incas. Today, this

subtropical delight is gaining an excellent reputation in premium

markets in the United States, Europe, Japan, and elsewhere. (T. Brown)

Industrialized

Regions. The climatic conditions required by the cherimoya

are found in pockets of southern Europe (for example, Spain and Italy),

the eastern Mediterranean (Israel), the western United States, coastal

Australia, and northern New Zealand. In these areas, the fruit could

become a valuable crop. In Australia and South Africa, the cherimoya

hybrid known as atemoya is already commonly cultivated.

The cherimoya could have an impact on international fruit markets. The

United Kingdom is already a substantial importer, and, as superior

cultivars and improved packing become commonplace, cherimoyas could

become as familiar as bananas.

USES

The cherimoya is essentially a dessert fruit. It is most often broken

or cut open, held in the hand, and the flesh scooped out with a spoon.

It can also be pureed and used in sauces to be poured over ice creams,

mousses, and custards. In Chile, cherimoya ice cream is said to be the

most profitable use. It is also processed into nectars and fruit salad

mixes, and the juice makes a delicious wine.

NUTRITION

Cherimoya is basically a sweet fruit: sugar content is high; acids,

low. It has moderate amounts of calcium and phosphorus (34 and 35 mg

per 100 g). Its vitamin A content is modest, but it is a good source of

thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin. 1

HORTICULTURE

Because

seedling trees usually bear fruits of varying quality, most commercial

cherimoyas are propagated by budding or grafting clonal stock onto

vigorous rootstock. However, a few forms come true from seed, and in

some areas seed propagation is used exclusively.

The trees are usually pruned during their brief deciduous period (in

the spring) to keep them low and easy to manage. The branches are also

pruned selectively after the fruit has set—for example, to prevent them

rubbing against the fruits or to encourage them to shade the fruits.

(Too much direct sunlight overheats the fruits, cracking them open.)

Under favorable conditions, the trees begin bearing 3–4 years after

planting. However, certain cultivars bear in 2–3 years, others in 5–6

years. Many growers prop or support the branches, which can get so

heavily laden they break off.

Pollination can be irregular and unreliable. The flowers have such a

narrow opening to the stigmas and ovaries that it effectively bars most

pollen-carrying insects. Honeybees, for instance, are ineffective. 2

In South America, tiny beetles provide pollination, 3

but in some other places (California, for instance) no reliable

pollinators have been found. There, hand pollination is needed to

ensure a high proportion of commercial-quality fruit. 4

HARVESTING AND HANDLING

The fruits are harvested by hand when the skin becomes shiny and turns

a lighter shade of green (about a week before full maturity). A heavy

crop can produce over 11,000 kg of quality fruits per hectare.

LIMITATIONS

A cherimoya plantation is far from simple to manage. The trees are

vulnerable to climatic adversity: heat and frost injure them, low

humidity prevents pollination, and winds break off fruit-laden

branches. They are also subject to some serious pests and diseases.

Several types of scale insects, leaf miners, and mealy bugs can infect

the trees, and wasps and fruit flies attack the fruits.

Pollination is perhaps the cherimoya's biggest technical difficulty.

Not only are reliable pollinators missing in some locations, but low

humidity, especially when combined with high temperatures, causes

pollination failure; these conditions dry out the sticky stigmas, and

the heavy pollen falls off before it can germinate.

Hand pollination is costly and time consuming. However, it improves

fruit set of all cultivars under nearly all conditions. It enhances

fruit size and shape. It allows the grower to extend or shorten the

season (by holding off on pollination) as well as to simplify the

harvesting (by pollinating only flowers that are easy to reach). 5

The fruits are particularly vulnerable to climatic adversity: if caught

by cold weather before maturity, they ripen imperfectly; if rains are

heavy or sun excessive, the large ones crack open; and if humidity is

high, they rot before they can be picked.

The fruits must be picked by hand, and, because they mature at

different times, each tree may have to be harvested as many as 10

times. In addition, the picked fruits are difficult to handle. Even

when undamaged, they have short storage lives (for example, 3 weeks at

10°C) unless handled with extreme care. The fruit has a culinary

drawback: the large black seeds annoy many consumers. However, fruits

with a low number of seeds exist, 6 and there

are unconfirmed reports of seedless types. So far, however, neither

type has been produced on a large scale.

RESEARCH NEEDS

The following are six important areas for research and development.

Germplasm

The danger of losing unique and potentially valuable types is high. A

fundamental step, therefore, is to make an inventory of cherimoya

germplasm and to collect genetic material from the natural populations

as well as from gardens and orchards, especially throughout the Andes.

Selection

Future commercialization will depend on the selection of cultivars that

dependably produce large numbers of well-shaped fruit with few seeds

and good flavor. Selection criteria could include: resistance to

diseases and pests, regular heavy yields of uniform fruit with smooth

green skin, juicy flesh of pleasant flavor, few or no seeds, resistance

to bruising, and good keeping qualities.

Pollination

The whole process of pollination should be studied and its impediments

clarified. Currently few, if any, specific insects have been definitely

associated with cherimoya pollination. 7 The

insects that now pollinate it in South America should be identified.

Spain, where good natural fruit set is common in most orchards, might

also teach much. 8 Selecting genotypes that

naturally produce symmetrical, full-sized fruits may reduce or

eliminate the need to hand pollinate, bringing the cherimoya a giant

step forward in several countries.

Cultural

Practices Horticulturists have not learned enough to

clearly understand the plant's behavior and requirements. Knowledge of

the effects of pruning, soils, fertilization, and other cultural

details is as yet insufficient. The current complexity of management

should be simplified.

Evaluation of the plants in the Andes, and the ways in which farmers

handle them, could provide guidance for mastering the species'

horticulture. Also, there is a need for practical trials to identify

more precisely the limits of the tree's environmental and management

requirements.

Intensive cultural methods, such as trellising and espaliering, 9

may help achieve maximum production of high-quality fruits. These

growing systems facilitate operations such as hand pollination; they

also provide support for heavy crops.

Breeding

Ongoing testing of superior cultivars is needed. Low seed count, good

keeping quality, and good flavor have yet to coincide in a cultivar

that also has superior horticultural qualities. In addition, it is

advisable to grow populations of seedling cherimoyas in all areas where

this crop is adapted. From these variable seedling plants, selections

based on local environmental conditions can be made. Elite seedling

selections can be multiplied by budding or grafting. Mass propagation

of superior genotypes by tissue culture could also provide large

numbers of quality plants.

Improved cherimoyas might be developed by controlled crosses and,

perhaps, by making sterile, seedless triploids. Breeding for large

flowers that can be more easily pollinated might even be possible.

Hybridization

Members of the genus Annona

hybridize readily with each other, so there is considerable potential

for producing new cherimoyalike fruits (perhaps seedless or

pink-fleshed types) that have valuable commercial and agronomic traits.

Handling

Improved techniques for handling, shipping, and storing delicate fruits

would go a long way to helping the cherimoya fulfill its potential.

Ways to reduce the effects of ethylene should be explored. Cherimoyas

produce this gas prodigiously, and in closed containers it causes them

to ripen extremely fast.

SPECIES INFORMATION

Botanical Name

Annona

cherimola Miller

Family

Annonaceae (annona family)

Common Names

Quechua: chirimuya

Aymara: yuructira

Spanish: chirimoya, cherimoya, cherimalla, cherimoyales, anona del

Perú, chirimoyo del Perú, cachimán de la China, catuche, momona,

girimoya, masa

Portuguese: cherimólia, anona do Chile, fruta do conde, cabeça de negro

English: cherimoya, cherimoyer, annona

French: chérimolier, anone

Italian: cerimolia

Dutch: cherimolia

German: Chirimoyabaum, Cherimoyer, Cherimolia, peruanischer, Flaschenbaum, Flachsbaum

Origin.

The cherimoya is apparently an ancient domesticate. Seeds have been

found in Peruvian archeological sites hundreds of kilometers from its

native habitat, and the fruit is depicted on pottery of pre-Inca

peoples. The wild trees occur particularly in the Loja area of

southwestern Ecuador, where extensive groves are present in sparsely

inhabited areas.

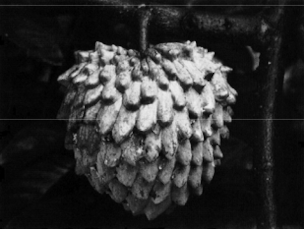

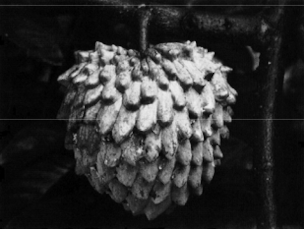

Description. A small, erect, or sometimes spreading

tree, the cherimoya rarely reaches more than 8 m in height. It often

divides at the ground into several main stems. The light-green,

three-petaled, perfect flowers are about 2.5 cm long. The fruit is an

aggregate, composed of many fused carpels. Depending on degree of

pollination, the fruits are heart-shaped, conical, oval, or irregular

in shape. They normally weigh about 0.5 kg, with some weighing up to 3

kg. Moss green in color, they have either a thin or thick skin; the

surface can be nearly smooth, but usually bears scalelike impressions

or prominent protuberances.

Horticultural Varieties. A number of cultivars have been developed.

Nearly

every valley in Ecuador has a local favorite, as do most areas where

the fruit has been introduced. Named commercial varieties include

Booth, White, Pierce, Knight, Bonito, Chaffey, Ott, Whaley, and Oxhart.

These exhibit great variation in climatic and soil requirements.

In Spain, 200 cultivars from 10 countries are under observation. 10

Environmental Requirements

Daylength.

Apparently neutral. In its flower-bud formation, this plant does not

respond to changes in photoperiod as most fruit species do.

Rainfall.

The plant does not tolerate drought well. For good production, it needs

a fairly constant source of water. In Latin America, the tree thrives

under more than 1,200 mm rainfall during the growing season. As noted,

high humidity assists pollen set, and a dry period during harvesting

prevents water-induced damage to fruit. Also, water stress just before

flowering may increase flower (and hence fruit) production.

Altitude.

The cherimoya does best in relatively cool (but not cold) regions, and

is unsuited to the lowland tropics. (In equatorial regions it produces

well only at altitudes above 1,500 m.)

Low Temperature.

The plant is frost sensitive and is even less hardy than avocados or

oranges. Young specimens are hurt by temperatures of `2°C.

High Temperature.

The upper limits of its heat tolerance are uncertain, but is is said

that the tree will not set fruit when temperatures exceed 30°C.

Soil Type.

Cherimoya can be grown on soils of many types. The optimum acidity is

said to be pH 6.5–7.5. On the other hand, the tree seems particularly

adapted to high-calcium soils, on which it bears abundant fruits of

superior flavor. Because of sensitivity to root rot, the tree does not

tolerate poorly drained sites.

Related Species. The genus Annona,

composed of perhaps 100 species mostly native to tropical America,

includes some of the most delectable fruits in the tropics. Most are

similar to the cherimoya in their structure. Examples are:

• Sugar apple, or sweetsop (Annona squamosa).

Subtropical and tropical. The fruit is 0.5–1 kg, and yellowish green or

bluish. It splits when ripe. The white, custardlike pulp has a sweet,

delicious flavor.

• Soursop, or guanabana (A. muricata).

This evergreen tree is the most tropical of the annonas. The

yellow-green fruit—one of the best in the world—is the largest of the

annonas, sometimes weighing up to 7 kg. The flesh resembles that of the

cherimoya, but it is pure white, more fibrous, and the flavor, with its

acidic tang, is “crisper.”

• Custard apple, or annona (A. reticulata).

This beige to brownish red fruit often weighs more than 1 kg. Its

creamy white flesh is sweet but is sometimes granular and is generally

considered inferior to the other commonly cultivated annonas. However,

this plant is the most vigorous of all, and types that produce seedless

fruits are known.

• Ilama (A. diversifolia).

This fruit has a thick rind; its white or pinkish flesh has a subacid

to sweet flavor and many seeds. It is inferior to the cherimoya in

quality and flavor, but it is adapted to tropical lowlands where

cherimoya cannot grow.

• A. longipes.

This species is closely related to cherimoya and is known from only

three localities in Veracruz, Mexico, where it occurs at near sea

level. Its traits would probably complement cherimoya's if the two

species were hybridized to create a new, man-made fruit. 11

ATEMOYA

Like the cherimoya, the atemoya has promise for widespread cultivation.

This hybrid of the cherimoya and the sugar apple was developed in 1907

by P.J. Wester, a U.S. Department of Agriculture employee in Florida.

(Similar crosses also appeared naturally in Australia in 1850 and in

Palestine in 1930.) The best atemoya varieties combine the qualities of

both cherimoya and sugar apple. However, the fruits are smaller and the

plant is more sensitive to cold.

The atemoya has been introduced

into many places and is commercially grown in Australia, Central

America, Florida, India, Israel, the Philippines, South Africa, and

South America. In eastern Australia, for at least half a century, the

fruit has been widely sold under the name “custard apple.”

The

atemoya grows on short trees—seldom more than 4 m high. The yellowish

green fruit has pulp that is white, juicy, smooth, and subacid. It

usually weighs about 0.5 kg, grows easily at sea level, and apparently

has no pollination difficulties.

The fruit may be harvested when

mature but still firm, after which it will ripen to excellent eating

quality. It finds a ready market because most people like the flavor at

first trial. It is superb for fresh consumption, but the pulp can also

be used in sherbets, ice creams, and yogurt.

Seedling progeny are

extremely variable, and possibilities for further variety improvement

are very good. So far, however, little work has been done to select and

propagate superior varieties.

1 Information from S. Dawes.

2 The male and female organs of a

flower are fertile at different times. Honeybees visit male-phase

flowers but not female-phase flowers, which offer no nectar or pollen.

3 Reviewer G.E. Schatz writes:

"Pollination is undoubtedly effected by small beetles, most likely

Nitidulidae. They are attracted to the flowers by the odor emitted

during the female stage, a fruity odor that mimics their normal mating

and ovipositing substrate, rotting fruit. There is no other reward per

se, and hence it is a case of deception. The beetles often will stay in

a flower 24 hours the flower offers a sheltered mating site, safe from

predators during daylight hours. Studies on odor could lead to improved

pollination."

4 California growers use artists'

paint brushes with cut-down bristles to collect pollen in late

afternoon. The next morning they apply it to receptive female flowers.

5 Schroeder, 1988.

6 Flesh: seed weight ratios from 8:1

to 30:1 have been reported.

7 Schroeder, 1988.

8 Information from J. Farré.

9 It has been reported that on

Madeira, trees were espaliered so successfully that in some locations

they have replaced grapes, the main crop of the island. The branches

were trained so that fruit ripened in shade.

10 Information from J. Farré.

11 Information from G.E. Schatz

|

|