The Breadfruit and Its Relatives

The breadfruit contains considerable amounts of starch even when ripe.

The ash, fiber, and protein are high. The Samoan breadfruit was

analyzed at a riper stage than the Hawaiian specimen, which may account

for the larger proportion of starch to sugars in the

former. Notwithstanding their very different appearance, the

breadfruits are of the same family (Moraceae) as the mulberries, fig,

and osage orange. The breadfruits, however, are tropical, whereas the

fig is grown as a warm-temperate and subtropical fruit. The genus

Artocarpus, comprising the breadfruit and its relatives, includes some

30 species.

The breadfruit

Artocarpus communis Forst.

Among the horticultural products brought to the attention of Europeans

by the early voyagers to the East, few were considered of such interest

and value as the breadfruit. The importance of its introduction into

the British colonies in the West Indies was felt to be so great that

His Majesty's government toward the end of the eighteenth century

fitted out an expedition for the sole purpose of transporting the

plants from Tahiti, in Polynesia, to Jamaica and other islands in the

American tropics. On the failure of this expedition, due to the mutiny

of the crew, a second and successful one was undertaken.

Contrary to expectations, the breadfruit did not prove of great value

to the West Indian colonies. The banana is more productive and gives

more prompt returns, and the negroes preferred to continue eating a

fruit to which they were accustomed rather than trouble to cultivate

the taste for a new one.

In Polynesia, however, the breadfruit still retains the important

position which it occupied at the time the region was first visited by

Europeans. There it is a staple food and really entitled, by reason of

its starchy character and the role which it plays in the native

dietary, to the name which has been bestowed on it by the English.

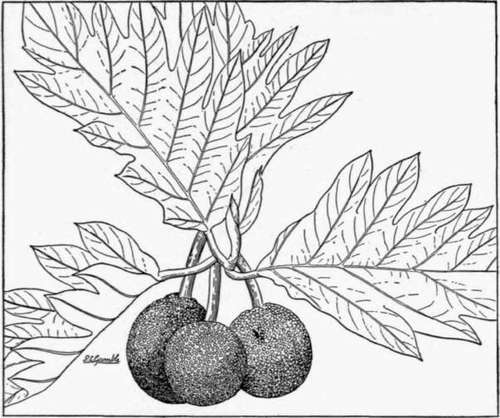

Fig. 52. The breadfruit (Artocarpus communis)

is one of the staple foodstuffs of the Polynesians. It is cultivated on

a limited scale in tropical America, where it was introduced toward the

end of the eighteenth century. (X about 1/7)

The tree, when well grown, is one of the handsomest to be seen within

the tropics. It reaches a height of 40 to 60 feet, and has large,

ovate, leathery leaves which are entire at the base and three- to

nine-lobed toward the upper end. Male and female flowers are produced

in separate inflorescences on the same tree. The staminate or male

flowers grow in dense, yellow, club-shaped catkins ; the female, which

are very numerous, are grouped together and form a large prickly head

upon a spongy receptacle. The ripe fruit, which is composed of the

matured ovaries of these female flowers, is round or oval in form,

commonly 4 to 8 inches in diameter, green when immature but becoming

brownish and at length yellow. The pulp is fibrous, pure white in the

immature fruit and yellowish in the fully ripe one. The fruits are

produced on the small branches of the tree upon short, thick stalks.

Clusters of two or three are common.

There are two classes of breadfruits, one seedless and the other

carrying seeds. The former is propagated vegetatively, and is

presumably the product of cultivation; the latter is often found in a

wild state, and is not used in the same manner as the seedless kind.

The seeds resemble chestnuts in size and appearance. The breadfruit is

believed to be a native of the Malayan Archipelago, where it has been

cultivated since antiquity. From its native region it was carried to

the islands of the Pacific in prehistoric times.

Henry E. Baum1, who

has written a lengthy history of this fruit, comments: "The open-boat

journeys of the Polynesians in their peopling of the Pacific islands

are marvelous from the point of view of seamanship alone. . . . Probably a hundred species of plants were introduced into Hawaii

by the Polynesians, and as a majority of their principal food-producing

plants were propagated by cuttings alone, the difficulty in

successfully carrying them across a wide expanse of ocean in open boats

is obvious."

1 Plant World, VI, 1903.

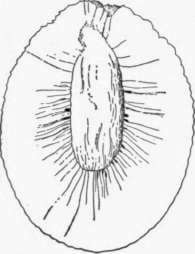

Fig. 53. The breadfruit, showing its internal

structure. This is the

seedless variety, generally cultivated in Polynesia; the other form has

seeds as large as chestnuts, and is not highly valued. (X about 1/4)

Spanish voyagers who visited the Solomon Islands in the sixteenth

century encountered the breadfruit, and it is believed that it must

also have been seen by the early Dutch and Portuguese sailors. In 1686

Captain William Dampier observed the plant at Guam and gave to the

world an accurate description of the fruit and its uses. The famous

Captain Cook, who explored the Pacific from 1768 until he met his death

in the Sandwich Islands in 1779, is said to have suggested to the

British the desirability of introducing the tree into the West Indies.

The outcome was that notorious voyage under William Bligh, in the

Bounty, which forms certainly the most dramatic incident in the history

of plant introduction.

The expedition sailed from England in 1787, and reached Tahiti, after a

cruise of ten months, in 1788. A thousand breadfruit plants were

obtained and placed on board ship in pots and tubs which had been

provided for the purpose. Before the ship was out of the South Seas the

crew, who had become enchanted with Tahitian life, mutinied and took

charge of the ship, putting their commander and the eighteen men who

remained loyal to him in a launch and setting them adrift. The mutinous

crew sailed back to Tahiti, whence some of the members, accompanied by

a number of Tahitians, migrated to Pitcairn's Island and established

there an Utopian colony. After a trying voyage Bligh and his companions

reached Tofoa, an island in the Tonga group, but they met with a

hostile reception from the natives and were forced to continue their

desperate pilgrimage. Fearing, because of their defenseless condition,

to land on the Oceanic islands, they steered for the distant East

Indies, which they were successful in reaching. "It appeared scarcely

credible to ourselves," remarks Captain Bligh in his account of the

voyage, "that, in an open boat so poorly provided, we should have been

able to reach the coast of Timor in forty-one days after leaving Tofoa,

having in that time run, by our log, a distance of 3618 miles; and

that, notwithstanding our extreme distress, no one should have perished

in the voyage."

Undaunted by the failure of the first attempt, a second was fitted out,

again under the command of Bligh, who was promoted to the rank of

Captain in the Royal Navy. This expedition, which sailed in 1792,

secured 1200 breadfruit plants, as well as other valuable trees, and

safely brought them to the West Indies.

The seeded breadfruit, which is much less valuable than the seedless

variety, was introduced into the West Indies by the French ten years

previous to Bligh's successful voyage.

At the present day the breadfruit is cosmopolitan in its distribution.

Regarding its occurrence in Hawaii, Vaughan MacCaughey1 says: "At the time of the coming of the first European explorers the

breadfruit was plentiful around the native settlements and villages on

all the islands: more plentiful than it has been at any subsequent

period. It thrives in the humid regions of Kona and Hilo, on the island

of Hawaii, and to-day there are many abandoned trees in these

districts, marking the sites of once-populous Hawaiian villages. The

extensive breadfruit groves of Lahaina, on Maui, were long famous for

the excellence of their fruit. In humid valleys on Molokai, Oahu, and

Kauai, the tree was also abundant, rearing its splendid dome of glossy

foliage high above the surrounding vegetation.

'It is distinctly a tree of the valleys and lowlands in Hawaii, and

with the decadence of the Hawaiian population, and the utilization of

fertile lowlands for sugar plantations, the majority of these fine old

trees were sacrificed to make way for the white man's agriculture."

1 Torreya, March, 1917.

In some of the Polynesian Islands, the tree is of such ancient

cultivation, and plays such an important part in the life of the

people, that the natives are unable to conceive of a land where the

breadfruit is not found.

Westward from Polynesia and its native region (the Malay Archipelago),

the breadfruit is grown in Ceylon and occasionally in India. In the

American tropics it is nowhere an important product, but it is

cultivated on a limited scale in the West Indies, the lowlands of

Mexico and Central America, and on the South American mainland as far

south as the state of Sao Paulo in Brazil.

There are probably no places on the mainland of the United States where

it can be cultivated successfully. All parts of California

unquestionably are too cold for it. Trees have been planted in extreme

southern Florida, but so far as is known none has ever reached bearing

stage, although there are fruiting specimens of the allied jackfruit in

that state.

The seedless variety is invariably called breadfruit in English; the

seeded variety sometimes breadnut. The Spanish name for the seedless

form is arbol del pan, sometimes masa pan; the French arbre a pain; the

Portuguese arvore do pao or fruta pao; the Italian albero del pane; and

the German brotbaum. W. E. Safford1 gives the following vernacular

names : Seedless variety, - lemae, lemai, lemay, rima (Guam); rima,

colo, kolo (Philippines); 'ulu (Samoa, Hawaii); uto (Fiji). Seeded

variety, - dugdug, dogdog (Guam); tipolo, antipolo (Philippines);

'ulu-ma'a (Samoa); uto-sore (Fiji); bulia (Solomon Islands).

Botanically the breadfruit is Artocarpus communis, Forst. The name

Artocarpus incisa, L. is a synonym.

The methods of preparing breadfruit for eating are numerous. Safford

writes: "It is eaten before it becomes ripe, while the pulp is still

white and mealy, of a consistency intermediate between new bread and

sweet potatoes. In Guam it was formerly cooked after the manner of most

Pacific island aborigines, by means of heated stones in a hole in the

earth, layers of stones, breadfruit, and green leaves alternating. It

is still sometimes cooked in this way on ranches; but the usual way of

cooking it is to boil it or to bake it in ovens; or it is cut in slices

and fried like potatoes. The last method is the one usually preferred

by foreigners. The fruit boiled or baked is rather tasteless by itself,

but with salt and butter or with gravy it is a palatable as well as a

nutritious article of diet."

1 Useful Plants of Guam.

Alice R. Thompson of Hawaii, who has published analyses of two

varieties, says on the point of nutritive value: "The breadfruit is

included in the table with bananas because it contains such high

amounts of carbohydrates. In comparing it with the banana the

hydrolyzable carbohydrates are seen to be much greater in amount. Miss

Thompson's two analyses are as follows:

| Variety |

Total Solids |

Ash |

Acids |

Protein |

Total Sugars |

Fat |

Fiber |

Hydrolysable Carbohydrates other than Sucrose |

| Hawaiin |

41.82 |

.95 |

.04 |

1.57 |

9.49 |

.19 |

1.20 |

27.89 |

| Samoan |

26.89 |

1.15 |

.07 |

1.57 |

14.60 |

.51 |

.97 |

9.21 |

The above statements of uses and content apply solely to the seedless

variety. In the seeded form the flesh or pulp is of little value, but

the seeds, which are eaten roasted or boiled, are highly relished. They

have something of the flavor of chestnuts.

The breadfruit tree is put to many uses in the Pacific islands.

1 Report of the Hawaii Exp. Stat., 1914.

Cloth and a kind of glue or calking material are obtained from it,

while the leaves are excellent fodder for live-stock.

In climatic requirements the tree is strictly tropical. Mac-Caughey

sums up the necessary factors as: "A warm, humid climate throughout the

year; copious precipitation; moist, fertile soil; and thorough

drainage. The absence of any one of these conditions is a serious

detriment to the normal growth of the plant, or may wholly prevent its

fruiting. It is scarcely tolerant of shade, and in Hawaii large trees

are almost invariably found growing in the open."It may be observed

that in those parts of Central America where the breadfruit is

cultivated it is found only in the lowlands, disappearing at elevations

of about 2,000 feet. It is evident, therefore, that it is only

successful in regions of uniformly warm climate.

Propagation of the seedless breadfruit is effected in the Pacific

islands by means of sprouts from the roots. Mac-Caughey writes: "When

growing in the soft moist soil which it prefers, the breadfruit roots

shallowly and widely. Often a network of exserted roots is visible

above the ground. This habit is of the greatest value in propagation.

The wounding or bruising of the root at any given point stimulates the

production of an offshoot, and young plants for transplanting are

produced solely in this way. This mode of propagation is naturally very

slow and laborious, as the young shoots grow slowly, and are very

sensitive to injury."

P. J. Wester has developed in the Philippines a method which is more

expeditious and satisfactory. Root-cuttings are used. The method is

described by him as follows:

"A plant bed or frame should be filled with medium coarse river sand to

a depth of 7 or 8 inches, - beach sand will do provided the salt has

been thoroughly washed out. If sand is not procurable, sandy loam may

be used.

"Larger cuttings may be made, but for the sake of convenience in

handling and in order not to impose too severe a strain upon the tree

that supplies the material, it is inadvisable to dig up roots for

cuttings that are more than 2\ inches in diameter. Roots less than

inch in diameter should be discarded. Root cuttings 10 inches long have

been very successful, but it is probable that a length of 8 inches

would prove sufficient, and, if so, this would allow the propagation of

a larger number of cuttings from a given amount of roots than if longer

cuttings were made."

"Saw off the roots into the proper lengths and smooth the cuts with a

sharp knife. Then make a trench and place the cuttings diagonally in

the sand, leaving about 1 ½ to 2 ½ inches of the thickest end of

each cutting projecting above the surface, pack the sand well, water,

and subsequently treat like hardwood cuttings. When the cuttings are

well rooted and have made a growth of eight to ten inches, transplant

to the nursery. Great care should be exercised in not bruising, drying,

or otherwise injuring the material from the digging of the roots to the

insertion of the cuttings in the sand."

"The work should be done during the rainy season."

Seeds of the seeded breadfruit do not retain their vitality more than a

few weeks, and should be planted promptly after they are removed from

the fruit.

The varieties of the seedless breadfruit are numerous but imperfectly

known. As many as twenty-five are said to occur in the Pacific islands,

although MacCaughey states that only three are known in Hawaii. It is a

curious circumstance that a tree as important as the breadfruit should

have received so little scientific study; but exceedingly little is

known regarding the cultural methods best suited to it and the relative

merits of the different varieties propagated vegetatively. Concerning

such matters as its place in Polynesian folklore, its history, and the

uses of the fruit, however, there is an abundance of information in the

accounts of early voyages as well as in the writings of modern authors.

The Jackfruit, Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

The Marang, Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

Back to

Breadfruit

Page

|